[ad_1]

(The Conversation) — An important piece of early Christian history, the Crosby-Schøyen Codex, is up for auction at Christie’s in London. This codex is a mid-fourth century book from Egypt containing a combination of biblical and other early Christian texts.

The Crosby-Schøyen Codex was discovered alongside more than 20 other codices near Dishna, Egypt, in 1952. These manuscripts are collectively known as “the Dishna Papers” or “the Bodmer Papyri,” after the Swiss collector Martin Bodmer.

Though often overshadowed by other 20th century discoveries, this trove of ancient manuscripts represents one of the most significant finds for understanding the history of early Christianity. As an expert on early Christian reading practices, I consider the Dishna Papers an invaluable witness to the formation of the Christian Bible. This ancient library shows how, before the consolidation of the Bible, early Christians read canonical and non-canonical scriptures – as well as pagan classics – side by side.

An overshadowed discovery

The middle decades of the 20th century were exciting years for scholars of early Christianity.

In 1945, a collection of 13 ancient codices was discovered near Nag Hammadi, Egypt. These contained dozens of otherwise unknown works, mostly associated with minority and marginalized forms of early Christianity. With titles like “The Gospel of Thomas” and “The Secret Revelation of John,” this cache of non-canonical scriptures captured the public’s imagination and inspired a bestseller.

Codices found at Nag Hammadi, Egypt.

The Gnostic Society Library

The very next year, Bedouin shepherds discovered ancient Hebrew scrolls hidden in a cave at Qumran on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea.

The “Dead Sea Scrolls” found in this and a dozen subsequently discovered caves constituted a massive library of Jewish texts, including biblical works and hitherto unknown texts with remarkable parallels to the writings of the New Testament. This find was celebrated in news stories, documentaries and other publications as among the greatest discoveries of the 20th century.

At the very same time, the Dishna Papers were discovered, smuggled out of Egypt and sold to European collectors with considerably less fanfare. No headline hailed the discovery of the Dishna Papers. Instead, pieces of this collection were sold to the highest bidders, scattering the ancient library across the globe.

The Dishna Papers

Though less exotic than Nag Hammadi or Qumran, the contents of the Crosby-Schøyen Codex and the 20-some additional codices discovered near Dishna have proved every bit as important for our understanding of early Christianity.

Two manuscripts of the canonical gospels, Luke and John, belonging to this ancient library predate almost every other surviving copy of these gospels. Scholars used these new manuscripts to revise the text of the New Testament.

For instance, the vast majority of manuscripts of the Gospel of John describe Jesus as “the only-begotten Son” (1:18). But the early manuscripts discovered at Dishna read “the only-begotten God.” Here and elsewhere, English translations of the Bible were changed to reflect the contents of the Dishna Papers.

But the library discovered near Dishna did not consist entirely of texts that ended up in the Christian Bible. Scriptures that were not included in the Christian canon, like Paul’s “Third Letter to the Corinthians” and “The Shepherd of Hermas,” were also found among the Dishna Papers.

One codex from Dishna contains the “Acts of Paul,” an extra-Biblical account of Paul’s travels and martyrdom. Another contains the “Infancy Gospel of James,” a non-canonical story about the life of Mary, Jesus’ mother. The discoveries at Dishna provide evidence that these writings, though unfamiliar to modern readers of the Bible, spent centuries on the periphery of Christian scripture.

The Dishna Papers included a few additional literary texts. One codex in this mostly Christian library contains several comedies by the Hellenistic playwright Menander. Another codex binds together a chapter of Thucydides’ “History of the Peloponnesian War” with a Greek version of the biblical Book of Daniel.

Evidently, the owner of this Christian library had no aversion to the arts and sciences of pre-Christian Hellenism. In this library, pagan classics and Christian scripture stood side by side.

But whose library was this?

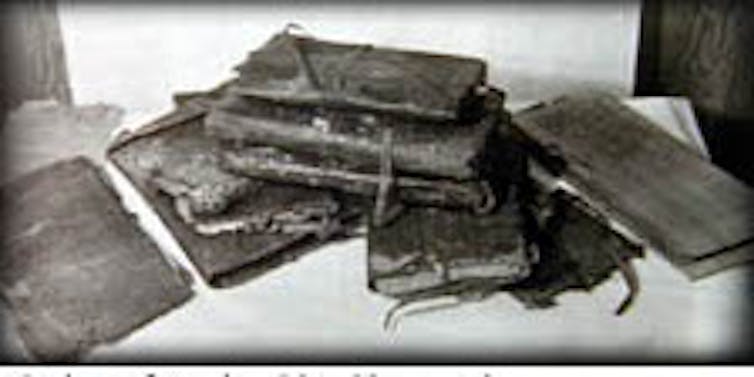

The Crosby-Schøyen Codex, written in Coptic, on papyrus.

The Schøyen Collection

The Crosby-Schøyen Codex, which is now up for sale, actually supplies several important clues to the origin of the Dishna Papers with which it was found.

Thanks to recent radiocarbon dating of this codex and the contents of a closely related manuscript, the Crosby-Schøyen Codex can be dated with some measure of confidence to the middle of the fourth century – roughly 325 to 350 C.E.

The Crosby-Schøyen Codex itself contains five texts in Sahidic Coptic, a dialect of the ancient Egyptian language. Three texts are Biblical: Jonah, Second Maccabees 5:27-7:41, and 1 Peter. The rest of the codex contains part of a well-known Easter homily and a brief otherwise unknown exhortation.

These texts, argue scholars Albert Pietersma and Susan Comstock, may have been collected into a single codex for use as an Easter lectionary. A lectionary is a collection of readings used in Christian worship services. Such lectionaries were used in Pachomian monasteries, like the one located only a few miles west of Dishna.

This monastery was established in the mid-330s by Pachomius, the reputed founder of communal monasticism. His Pachomian Rule, by which the monks would have ordered their communal life, makes frequent reference to the public and private use of books. Pachomius’ monasteries even taught illiterate monks to read.

It seems likely that this eclectic library of canonical and non-canonical scriptures, early Christian writings and pagan classics belonged to these book-loving monks in central Egypt. One of the Pachomian rules allowed monks to borrow books from the monastic library for up to one week.

Today, for a few million dollars, one such book can be yours forever. On June 11, 2024, the Crosby-Schøyen Codex will go to the highest bidder.

(Ian N. Mills, Visiting Assistant Professor of Classics and Religious Studies, Hamilton College. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()

[ad_2]