It is funny how when you first start doing something, you have so many misconceptions that you have to discard. When you look back on it, it always seems like you should have known better. That was the case when I first got a low-end laser cutter. When you want to cut or engrave something, it has to be in just the right spot. It is like hanging a picture. You can get really close, but if it is off just a little bit, people will notice.

The big commercial units I’ve been around all had cameras that were in a fixed position and were calibrated. So the software didn’t show you a representation of the bed. It showed you the bed. The real bed plus whatever was on it. Getting things lined up was simply a matter of dragging everything around until it looked right on the screen.

Today, some cheap laser cutters have cameras, and you can probably add one to those that don’t. But you still don’t need it. My Ourtur Laser Master 3 has nothing fancy, and while I didn’t always tackle it the best way, my current method works well enough. In addition, I recently got a chance to try an XTool S1. It isn’t that cheap, but it doesn’t have a camera. Interestingly, though, there are two different ways of laying things out that also work. However, you can still do it the old-fashioned way, too.

Humble Beginnings

I started out with a Laser Master 2, but it really had no comfort features. You had to focus the laser by observing the beam, and there was nothing to help you with positioning. I thought I would be clever and have the laser cut a grid into a spoil board so I could lay things out. That didn’t work well at all.

There are a few reasons a grid like that isn’t as useful as you’d think. First, if you do want to try it, the board needs to be totally secure with respect to the laser cutter’s frame. Otherwise, if the board or laser moves, you are now off. Even just a little tilt or slide will show up in the finished product. But the big problem is the workpiece has to be totally square with the frame, or things will be crooked.

A Better Plan

It didn’t take many ruined pieces to realize I needed a better way. The answer turned out to be wrapping paper. A trip to the dollar store will give you plenty of wrapping paper, and it can be ugly — you don’t care what it looks like since you’ll use the back.

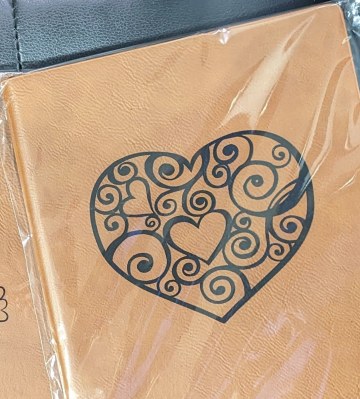

Suppose I’m going to engrave a notebook with a logo and name. I’ll have some outline representing the book. The steps are simple:

1) Put down the wrapping paper and tape it to the cutter’s bed.

2) Turn off everything and then turn on just the outline vector.

3) Focus on the paper and do the engrave.

Now, you have a perfect book-shaped rectangle on the paper. If the bed is tilted, it doesn’t matter because so is the rectangle.

4) Place the book inside the outline on the paper.

5) Refocus the laser.

6) Turn off the outline layer and turn on the other layers.

7) Burn!

The Laser Master 3 added a nice feature, which was a little hinged stick that flops out of the laser and lets you easily set the focus. I’d been doing that before with a little homemade cube, but it was nice to have it all set up.

No Camera, No Problem

The S1 is a fairly high-end machine for a diode laser, so I was a little surprised it didn’t have a camera. However, what it does have is closed-loop motor control. What that means is that if you move the laser head with your hands, the machine still knows where it is. There’s also a little laser pointer cross that shows you where the laser head is — sort of. There is an offset between the actual beam and the cross, but if you use their software, they know that. If you use Lightburn, you have to set that yourself.

So if you have a book you want to engrave on the bed, you tell the software to “mark.” It lets you pick a few shapes, but usually, you want a rectangle. You line up the laser cross with the top corner of the book (or whatever) and press the button on the machine. You hear a loud beep. Then, you move to the far bottom corner and press the button again. That’s it.

Now, the software will place a little box that shows exactly where the book is. This doesn’t help you correct for small skew problems, but it does let you accurately move things to the right location.

The machine also has an interesting way of dealing with autofocus. It has a metal pin that drops from the laser head sort of like a BL Touch on a 3D printer. When it hits something, it knows how far away the surface is. Then, it moves to a corner where a metal plate pushes the pin back up. You need to make sure the head is over something before you tell it to measure. If you have a honeycomb bed, the laser head will bottom out before the pin, and you’ll hear some ugly noises.

But A Picture is Worth…

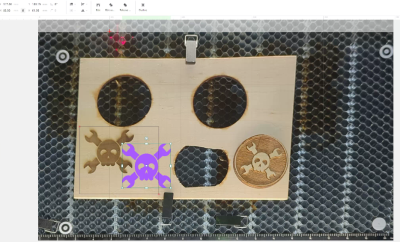

If you can’t stand not having an image of your workspace, the S1 can do it, but honestly, it is a pain. The printer comes with little sticky target decals, and you can make more if you need them. Three of them look like little bullseyes, and one is just a small dot. You place them somewhere on the bed where the laser can reach.

After you install the phone app, you can connect to the printer and calibrate the dots. You do this just like the marking routine. You aim at each target and press the button. Now, the software knows exactly where each bullseye is.

The next step is to take a picture of the bed with your phone. Since the software knows the bullseyes are circles and where they are, it can reconstruct a proper view of your bed. Moving it to your computer is a pain the first time since you have to scan a QR code on the computer to make a connection. After that, though, it just sends it. The problem, of course, is the shot isn’t live. You have to fix up the bed the way you want, shoot the picture, and then don’t change anything after that.

One tip: don’t cut anything on top of the bullseyes. They will blacken up and then you’ll need some extras. Not that we’ve done that, of course!

The Answer

It seems odd that cameras haven’t taken over everything. They work well, and a live view is handy. However, if you don’t have a camera, there are clear alternatives. For as much as the Xtool system is clever, it still doesn’t help you with crooked alignment. It is, however, better than the wrapping paper method for things where you don’t know the size already.

If you do know the size of the workpiece, though, it really isn’t that handy. Sure, you don’t have to tape down paper and score it with a framing cut, but that’s a small price to pay for the benefit you get. If we were building our own cutter, we’d seriously consider adding a probe, though.

How do you get engraving to go where you want it? Do you have another method? Let us know in the comments. If you haven’t splurged on a laser yet, you might enjoy a tutorial.