This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with the Mississippi Free Press. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

[ad_1]

Beneath the city of Jackson, Mississippi, is a Rube Goldberg-esque network of pipes that brings water to residents. The system, by one estimate, is twice as long as it should be for a city of this size. Much of it has been in disrepair for years; some parts are more than 100 years old.

Underground, broken pipes have spewed water into the surrounding earth or sent it bubbling up from cracked streets. For every gallon of water that reaches a customer’s tap, at least another gallon doesn’t, according to a June estimate from the manager of the water system.

Aboveground, the symptoms of those problems have been faucets that sputtered and toilet bowls that didn’t refill. Teenagers in the county’s juvenile-detention center were sent to other facilities to shower, one official said. Hospitals that regularly lost water built their own wells. Roughly every few days, people in one part of town or another have received notices telling them their water was unsafe to drink unless they boiled it first. At times, like for two weeks in the winter of 2021, many residents had no running water at all.

But for years, state employees inspecting Jackson’s primary water system noted few problems with the distribution system — the pipes that delivered water to its customers. In the 16 years before the system collapsed in 2022, leaving roughly 160,000 residents in and around Jackson dependent on bottled water for weeks, inspectors admonished the city just a couple times about the pipes underground. They identified issues with low water pressure just once and noted high water loss a few times. But they issued no formal reprimands or fines.

From 2006 through 2021, Jackson’s inspection score from the Mississippi State Department of Health, which oversees water systems in the state, averaged nearly 4 out of 5. The few times MSDH identified major problems in Jackson, all but one were tied to its water plants, not the distribution system.

This week, the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Inspector General said the state’s failure to flag ongoing problems in Jackson’s water system, including those in the pipes, contributed to the Jackson water crisis in August 2022. Over several years, the state’s inspections “did not reflect the conditions of Jackson’s system,” the inspector general’s staff wrote. As a result, they wrote, problems “were left unresolved until the eventual catastrophic failure of the system,” when the city’s main water plant finally buckled. It took weeks until the city could reliably pump clean water to residents.

Credit:

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

Credit:

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

The Office of Inspector General said the EPA, as the agency ultimately responsible for compliance with federal drinking water standards, shares some responsibility for the state’s failures because it didn’t make sure the state was properly enforcing its regulations. The agency said in a response included in the report that it agrees with the inspector general’s findings.

MSDH hasn’t responded to requests for comment on the report; its response to the Office of Inspector General wasn’t immediately available. But the findings aren’t exactly new to state regulators. The report, which covers inspections from 2015 through 2021, corroborates reporting by the Mississippi Free Press and ProPublica that looked at state inspections dating back to 2006.

The news outlets told MSDH this year that their reporting showed that the states’ inspections had failed to identify problems in the distribution system and to require the city to act. MSDH officials disputed the claim as “patently false,” saying its inspections were based on information provided by the city. The agency said the city of Jackson failed to take on the responsibility “to respond to any potential pressure or water loss issues.”

In an interview late last year, State Health Officer Dan Edney defended MSDH’s oversight. Still, he said he expected the EPA to tighten its rules on how states oversee water systems. “The EPA probably, after studying this event, is going to change some things in terms of how they want inspections to be, and I welcome that,” he told the Mississippi Free Press and ProPublica. Such changes, he said, would allow Mississippi “to intervene in a little bit more meaningful way, sooner.”

Such changes are indeed underway. In response to the inspector general’s report, the EPA plans to review how MSDH conducts federally required inspections. Beyond Mississippi, the EPA is checking other states’ oversight in the Southeast. And federal officials will update EPA guidance on how to perform federally required inspections to include a process for handling ongoing problems such as those that plagued Jackson’s distribution system.

Water Pressure Was Bad, but Still Passed the Test

MSDH’s inspections do include questions about the pipes underground. But time and again, the agency’s inspection records did not reflect what was going on beneath the surface in Jackson.

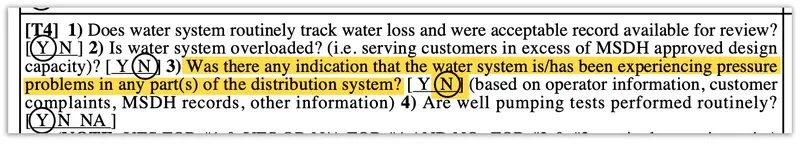

Every year when inspectors came, they checked water quality, reviewed records and policies and looked over equipment. They filled out a two-page questionnaire, awarded points based on the answers and wrote up pages of recommendations. On every inspection report from 2006 to 2020, inspectors answered no to a question about whether there was “any indication” of pressure problems. Only in 2021 did they answer yes, noting that a fire at a water plant had caused pressure to drop.

Credit:

Obtained by Mississippi Free Press and ProPublica. Highlighted by ProPublica.

Edney, who became the state’s chief health officer in 2022, admitted to the Mississippi Free Press and ProPublica that this was “surprising.” As a practicing physician, he had experienced water pressure problems at Merit Health Central, a hospital located in a part of town that was often the first to lose water during an outage.

There was other evidence as well: the city’s own boil-water notices, which alerted people to problems in the system. Low pressure resulting from a line break can allow bacteria to seep into the pipes, which is why Jackson residents regularly received such notices. From August 2014 through July 2022, Jackson issued more than 1,500 boil-water notices, according to city records in the possession of MSDH, including at least nine notices that affected everyone in the city. Such notices aren’t normally reported to the EPA. But, inspector general staff wrote, “if state surveyors find an exorbitant number of boil water notices” during a federally required inspection, “the state could report the issue to the EPA.”

The Mississippi Free Press and ProPublica asked Edney how inspectors could have noted pressure problems just once even as Jackson regularly shared boil-water notices with MSDH. Edney said the state doesn’t consider water pressure to be a problem unless it’s “consistently” below 20 pounds per square inch, and Jackson often posted pressures of 21 to 30 psi. “If they’re consistently running 22 psi, then they pass,” Edney said. “That’s an acceptable low pressure.”

Though that figure might be acceptable to Mississippi, it is much lower than the standard pressure specified in a set of guidelines that the EPA recommends water systems follow. Those guidelines, produced by a consortium of state water regulators, say that a water system’s “normal working pressure” must be at least 35 psi and generally should be between 60 and 80 psi.

Both MSDH and the EPA pointed out that these are just guidelines. There are no federal requirements for how high water pressure must be; the EPA says most states set the minimum at 20 psi to ensure that firefighters have the water they need.

Ken Kopocis, who led the EPA’s Office of Water during the Obama administration, said a water system operating on a thin margin like Jackson’s did is just “one small hiccup” away from an interruption in water service or a widespread outage. “This is going to happen,” he said. “It’s only a matter of happenstance that it got delayed as long as it did.”

Massive Water Loss Wasn’t a Problem for Inspectors

When pressure in a water system drops unexpectedly, there are two likely causes: a decline in water production at plants or water loss due to broken pipes.

Estimates suggest that for years, Jackson has lost half or even more of its treated water. It was a well-known problem among the people who ran the utility. In 2012, an engineering firm warned that the rate of water loss was increasing. In 2016, a public works official estimated that Jackson was losing 40% of its water, according to a news story at the time.

Data from the city’s water plants indicates the situation may have been even worse. Between 2013 and 2022, Jackson’s water plants produced an average of about 45 million gallons of treated water a day. On a normal day, the city should require 18 to 20 million gallons, according to Ted Henifin, the head of JXN Water, the federally appointed management firm now running the city’s water system.

Credit:

Steve Helber/AP

It wasn’t until after Henifin’s team took over the water system in 2022 that Terence Byrd, who managed one of the utility’s two water treatment plants for about five years, realized how those leaks contributed to the constant cycle of breakdowns and repairs at the plants. “Our plants were running into the ground,” said Byrd, who is now working for JXN Water, “because they were trying to pump against so many leaks in the system.”

Bill Miley, who was responsible for fixing those leaks when he served as utilities manager for the city of Jackson, said that work kept his ever-shrinking crews and hired contractors running nonstop. “I had enough to keep three crews busy near seven days a week,” he said.

The city experienced more than 7,300 breaks over a five-year period, according to the EPA inspector general, far above the industry benchmark. A former city official told federal employees that a single line break leaked 4 million to 5 million gallons a day — a total of 10 billion to 13 billion gallons from 2016 to 2022, according to the inspector general’s report. State inspectors, however, never flagged the frequent line breaks as a serious problem that warranted official corrective action.

Nor did they evaluate Jackson based on how much water it was losing. Their questionnaire asked only whether the city was tracking water loss at all and whether “acceptable” records were available for review. For all but two of 16 years, inspectors said Jackson’s records were fine.

The exception was in 2008 and 2009. The first year, inspectors noted that Jackson hadn’t provided acceptable records, which was considered a “significant deficiency,” and they told the city to respond with a plan to fix it. In 2009, state inspectors again noted the lack of records on their report. From 2010 on, MSDH’s inspection records show, the agency considered Jackson’s records acceptable.

Three current and former officials with Jackson’s water system told the news organizations that the inspection reports were wrong in calling the city’s water records acceptable. They explained that tracking water loss requires functional meters to measure how much water customers use. But in Jackson, the city’s water meters have been in a state of constant failure for at least the last decade. The city had no way to accurately calculate how much water it was losing, and officials knew it at the time.

In a written statement sent before the inspector general report was published, MSDH said that, under state law, there was nothing further the agency could have done to mandate that the records reflected reality. “There is no established and enforceable consequence of providing inaccurate water loss information,” the agency said. And there’s little chance that state lawmakers would grant the agency the authority to set a limit. The Legislature “is unlikely to support changing the regulatory environment for every public water system in the state as a result of Jackson and its specific lack of system maintenance,” MSDH officials said.

Inspectors eventually made note of Jackson’s water loss in their 2019 report, saying that city records showed that water loss was “around 50%.” The following two years, inspectors put it at more than 40%. Even then, Edney said MSDH had no authority to intervene because the state doesn’t have a limit on how much water a local utility can lose. “Maybe there needs to be,” he said.

The state’s limited approach to enforcement comes up repeatedly in the inspector general’s report. State employees overlooked some problems, and they didn’t consistently document others or escalate those that continued from year to year, inspector general staff wrote. When state employees did identify serious problems, they didn’t always notify the city and sometimes didn’t record them in an EPA database. As a result, the EPA didn’t know just how bad things were in Jackson.

A City That Couldn’t Count on the Water

The water system portrayed in the state’s inspection reports contrasted sharply with the experience of residents of Windsor Forest, a majority-Black neighborhood located far from the water plants and pumping stations.

For most of the six years that Paidra Evans has lived in the South Jackson neighborhood, she’s had trouble getting enough water to wash dishes or hose down her car. When the 2022 crisis hit, she was caring for her husband, a truck driver, as his health slowly declined. “A lot of times, when I had to bathe him on the bed, the water would be brown,” she said. “He couldn’t brush his teeth or anything. He said: ‘Baby, what is going on? Just let the water run, run, run, and then maybe it’ll get clear.’”

Credit:

Nick Judin/Mississippi Free Press

Her neighborhood “had been a focal point even before the crisis started,” JXN Water’s Byrd said. (As of October, JXN Water said it had transitioned the neighborhood to the city’s well system, alleviating these long-standing issues; Evans said her water pressure has improved.)

Miley, the city’s former utilities manager, was well aware of those problems. He said he knew something was wrong whenever he got a call from Merit Health Central. When the pressure dipped in the system, Merit would lose water above the fifth floor — a warning that others in the city weren’t getting water either.

Merit, which by 2015 was the only hospital in the city without its own water supply, eventually decided to pay $11,000 a month to park water trucks outside in case of an outage. The bill goes up to $10,000 per day when the hospital needs the water.

At the Henley-Young-Patton Juvenile Justice Center in South Jackson, every two months or so the water pressure would decline so severely that staff needed bottled water to cook and flush toilets, said Eddie Burnside, the facility’s operations manager. That started in 2018 and continued until at least 2023, he said.

In 2020, Hinds County installed a pump at the facility to draw water from the city’s pipes, Burnside said. But problems continued; Burnside said detainees drank bottled water when pressure dropped too low to trust what came out of the pipes.

Jordan Rae Hillman, JXN Water’s chief operating officer, confirmed in a written statement that pressure at Henley-Young dropped whenever there were significant line breaks anywhere in the city. She said it was a consequence of the facility’s relatively high elevation and the water system’s challenges in keeping the system pressurized.

Now, with the intervention of the federal government, pressure across the city has begun to increase. Melanie McMillan, Merit Health’s spokesperson, said the hospital has seen “tremendous improvement.”

That’s due to a drastic reduction in water loss, said Henifin, head of JXN Water. The city’s two plants now produce just 38 million gallons a day to meet demand, down from 55 million gallons a day last summer. “Great progress,” Henifin said; still, half of that water doesn’t make it to customers.

JXN Water has periodically monitored pressure outside Henley-Young, part of a new network of sensors across the city. The most recent measurement in February showed street-level pressure of 38 psi, just above what the guidelines recommended by the EPA say is the lower limit for normal pressure. Soon, a new jail nearby will provide well water, permanently freeing the juvenile facility from the city’s water service.

Though Mississippi regulators defended their oversight of the city’s water system, Edney acknowledged in two interviews that MSDH could do more to make sure communities have reliable, safe drinking water. When systems are out of compliance, the state will use the threat of fines to force water systems to make repairs, he said.

Kopocis, who headed the EPA’s Office of Water during the Obama years, echoed water regulators in a few other states in saying that the gaps exposed by the Jackson water crisis extend beyond Mississippi. Most states do not have water quality laws that are stricter than the federal government’s. And regulators in several states said inspectors there focus on water plants, not pipes.

That means problems like Jackson’s may go undetected before a major failure. Robert Brownwood, who works for California’s water regulator, said Jackson is like Flint, Michigan — another struggling, majority-Black city that made headlines for a water crisis beginning in 2014. “As Flint was for lead,” he said, “Jackson is the poster child for distribution infrastructure and repair.”

[ad_2]