Wireless networking is all-pervasive in our modern lives. Wi-Fi technology lives in our smartphones, our laptops, and even our watches. Internet is available to be plucked out of the air in virtually every home across the country. Wi-Fi has been one of the grand computing revolutions of the past few decades.

It might surprise you to know that Australia proudly claims the invention of Wi-Fi as its own. It had good reason to, as well— given the money that would surely be due to the creators of the technology. However, dig deeper, and you’ll find things are altogether more complex.

Big Ideas

It all began at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, or CSIRO. The government agency has a wide-ranging brief to pursue research goals across many areas. In the 1990s, this extended to research into various radio technologies, including wireless networking.

The CSIRO is very proud of what it achieved, crediting itself with “Bringing WiFi to the world.” It’s a common piece of trivia thrown around the pub as a bit of national pride—it was scientists Down Under that managed to cook up one of the biggest technologies of recent times!

This might sound a little confusing to you if you’ve looked into the history of Wi-Fi at all. Wasn’t it the IEEE that established the working group for 802.11? And wasn’t it that standard that was released to the public in 1997? Indeed, it was!

The fact is that many groups were working on wireless networking technology in the 1980s and 1990s. Notably, the CSIRO was among them, but it wasn’t the first by any means—nor was it involved with the group behind 802.11. That group formed in 1990, while the precursor to 802.11 was actually developed by NCR Corporation/AT&T in a lab in the Netherlands in 1991. The first standard of what would later become Wi-Fi—802.11-1997—was established by the IEEE based on a proposal by Lucent and NTT, with a bitrate of just 2 MBit/s and operating at 2.4GHz. This standard operated based on frequency-hopping or direct-sequence spread spectrum technology. This later developed into the popular 802.11b standard in 1999, which upped the speed to 11 Mbit/s. 802.11a came later, switching to 5GHz and using a modulation scheme based around orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM).

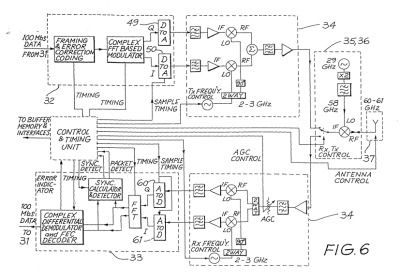

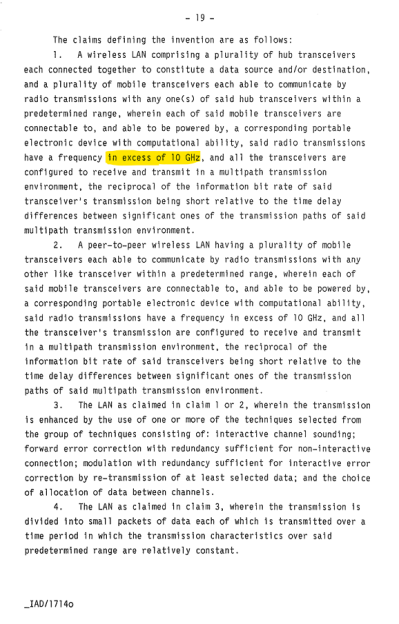

Given we apparently know who invented Wi-Fi, why are Australians allegedly taking credit? Well, it all comes down to patents. A team at the CSIRO had long been developing wireless networking technologies on its own. In fact, the group filed a patent on 19 November 1993 entitled “Invention: A Wireless Lan.” The crux of the patent was the idea of using multicarrier modulation to get around a frustrating problem—that of multipath interference in indoor environments. This was followed up with a later US patent in 1996 following along the same lines.

The patents were filed because the CSIRO team reckoned they’d cracked wireless networking at rates of many megabits per second. But the details differ quite significantly from the modern networking technologies we use today. Read the patents, and you’ll see repeated references to “operating at frequencies in excess of 10 GHz.” Indeed, the diagrams in the patent documents refer to transmissions in the 60 to 61 GHz range. That’s rather different from the mainstream Wi-Fi standards established by the IEEE. The CSIRO tried over the years to find commercial partners to work with to establish its technology, however, little came of it barring a short-lived start-up called Radiata that was swallowed up by Cisco, never to be seen again.

Steve Jobs shocked the crowd with a demonstration of the first mainstream laptop with wireless networking in 1999. Funnily enough, the CSIRO name didn’t come up.

Based on the fact that the CSIRO wasn’t in the 802.11 working group, and that its patents don’t correspond to the frequencies or specific technologies used in Wi-Fi, you might assume that the CSIRO wouldn’t have any right to claim the invention of Wi-Fi. And yet, the agency’s website could very much give you that impression! So what’s going on?

The CSIRO had been working on wireless LAN technology at the same time as everyone else. It had, by and large, failed to directly commercialize anything it had developed. However, the agency still had its patents. Thus, in the 2000s, it contested that it effectively held the rights to the techniques developed for effective wireless networking, and that those techniques were used in Wi-Fi standards. After writing to multiple companies demanding payment, it came up short. The CSIRO started taking wireless networking companies to court, charging that various companies had violated its patents and demanding heavy royalties, up to $4 per device in some cases. It contested that its scientists had come up with a unique combination of OFDM multiplexing, forward error correction, and interleaving that was key to making wireless networking practical.

A first test case against a Japanese company called Buffalo Technology went the CSIRO’s way. A follow-up case in 2009 aimed at a group of 14 companies. After four days of testimony, the case would have gone down to a jury decision, many members of which would not have been particularly well educated on the finer points of radio communications. The matter was instead settled for $205 million in the CSIRO’s favor. 2012 saw the Australian group go again, taking on a group of nine companies including T-Mobile, AT&T, Lenovo, and Broadcom. This case ended in a further $229 million settlement paid to the CSIRO.

We know little about what went on in these cases, nor the negotiations involved. Transcripts from the short-lived 2009 case had defence lawyers pointing out that the modulation techniques used in the Wi-Fi standards had been around for decades prior to the CSIRO’s later wireless LAN patent. Meanwhile, the CSIRO stuck to its guns, claiming that it was the combination of techniques that made wireless LAN possible, and that it deserved fair recompense for the use of its patented techniques.

Was this valid? Well, to a degree, that’s how patents work. If you patent an idea, and it’s deemed unique and special, you can generally demand a payment others that like to use it. For better or worse, the CSIRO was granted a US patent for its combination of techniques to do wireless networking. Other companies may have come to similar conclusions on their own, but that didn’t get a patent for it and that left them open to very expensive litigation from the CSIRO.

However, there’s a big caveat here. None of this means that the CSIRO invented Wi-Fi. These days, the agency’s website is careful with the wording, noting that it “invented Wireless LAN.”

It’s certainly valid to say that the CSIRO’s scientists did invent a wireless networking technique. The problem is that in the mass media, this has commonly been transliterated to say that the agency invented Wi-Fi, which it obviously did not. Of course, this misconception doesn’t hurt the agency’s public profile one bit.

Ultimately, the CSIRO did file some patents. It did come up with a wireless networking technique in the 1990s. But did it invent Wi-Fi? Certainly not. And many will contest that the agency’s patent should not have earned it any money from equipment built to standards it had no role in developing. Still, the myth with persist for some time to come. At least until someone writes a New York Times bestseller on the true and exact history of the real Wi-Fi standards. Can’t wait.