No parent wants to witness their child suffering from addiction, nor do they wish to see them end up as a sex worker. While the latter can sometimes be a choice, the first issue is broader, more dangerous, and often fatal. It’s easy to rush to judgment, to mock those who are in pain, but such reactions only deepen the wounds of the vulnerable. The world could be a better place if more people chose compassion, if they guided others toward the light rather than leading them into darkness.

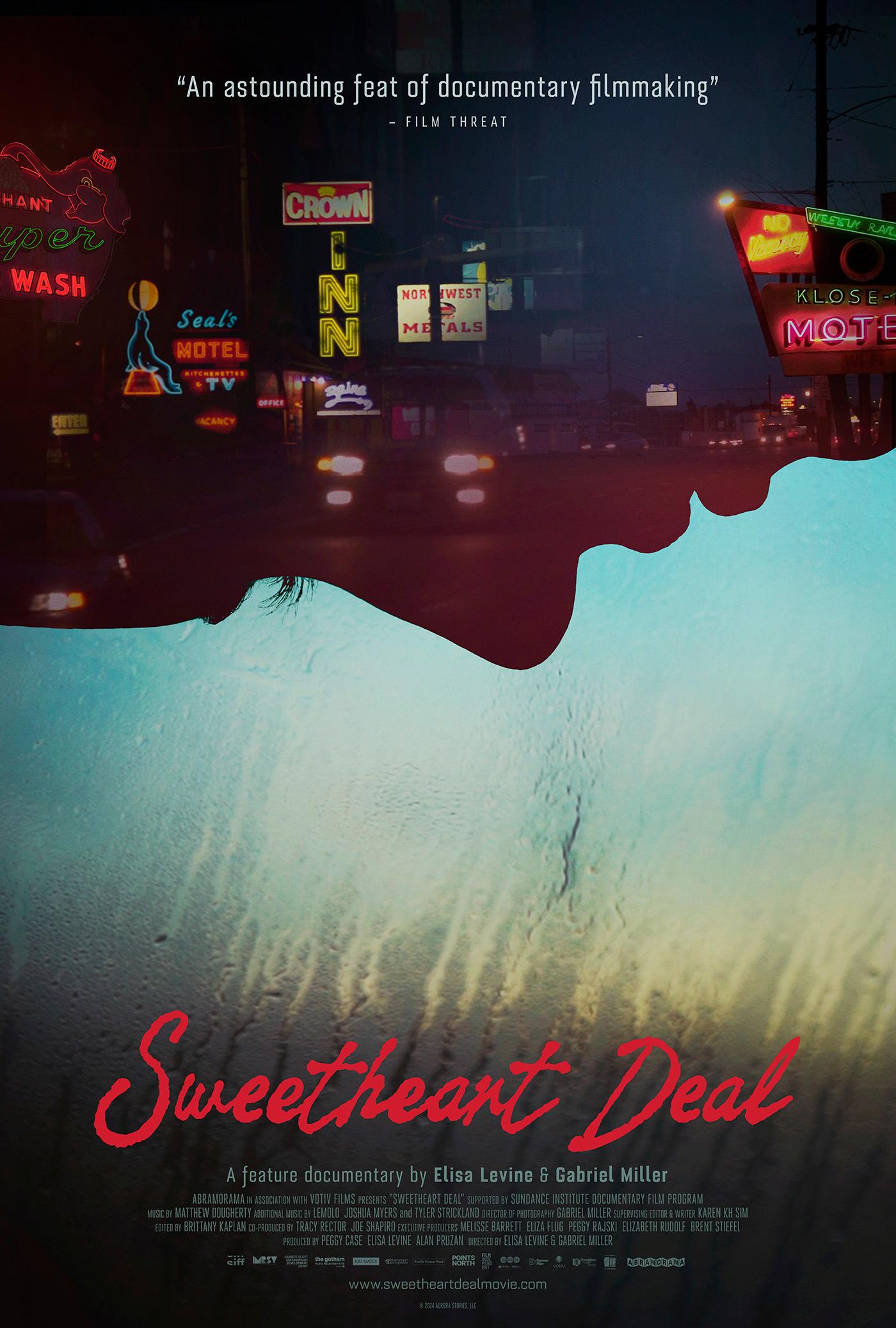

The Sweetheart Deal is a documentary that follows a group of women—sex workers who are fragile and vulnerable—finding what they believe to be a safe haven. This place, a motorhome, is owned by a man named Elliott, a mysterious figure whom these struggling women rely on as their savior. Kristine, Sara, Tammy, and Krista battle their addictions, though not all of them succeed. They sought refuge from the constant abuse of the outside world within Elliott’s motorhome, but they had no idea that an even greater danger lurked within those dark walls.

I must admit that anger, disgust, and frustration were the dominant emotions I felt throughout this film. As I watched, paying close attention to every detail shared by these four women, I could hardly imagine the horrors they endured daily. The sentiment of “I wish I knew” falls flat because, frankly, it is absolutely unacceptable that these women were left without help, abandoned to face a slow and torturous demise. But what will make you truly mad is the eventual and horrific revelation of the events that occurred within the motorhome, where Elliott, the so-called savior, committed acts of unspeakable evil, betraying those who relied on his “generosity” in the most heinous way.

Directors Elisa Levine and Gabriel Miller avoid the clichés often seen in films about drug addiction. They expose the raw truth, showing the reality of those who have no escape plan, who spiral into self-destruction. But can we truly blame those who lack the strength to overcome poverty, powerlessness, and addiction, especially when the system itself is ill-equipped to help them? Some might argue that it’s a personal choice, but once someone becomes an addict, that choice is stripped away.

There are a few hopeful stories of people rising above their circumstances, defeating the grip of addiction, but these are far outnumbered by the dead bodies left behind. Indifference is impossible after witnessing such a stark reality. That’s why documentaries like The Sweetheart Deal are so crucial—they keep us sober, awake, and aware. They remind us not to jump to conclusions without understanding the full picture. The film is powerful and poignant, but it’s also heartbreaking and gut-wrenching to realize what everyday life is like for those who are not fortunate enough to experience the beauty of life. And when they believe they do—it’s merely the result of what their bodies consume—a fleeting illusion of an excellent and carefree life that vanishes as soon as the effects wear off. But how do we convey this to those who most need to hear it? I don’t know. And after watching The Sweetheart Deal, it seems I may never know.

Like this:

Like Loading…

Related