[ad_1]

Politics

/

October 8, 2024

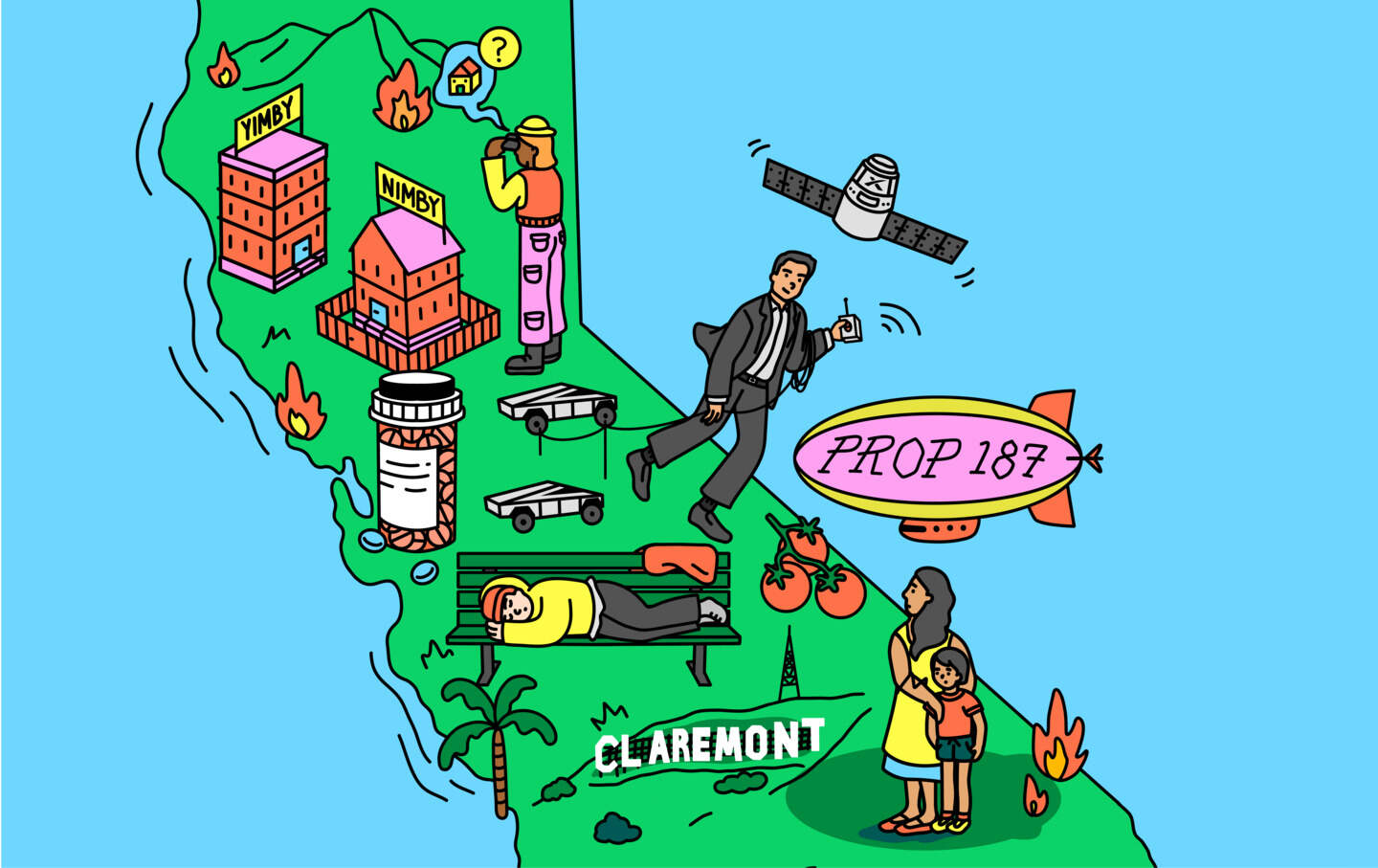

To understand US politics—for better and for worse—look to the Golden State.

In the preface to California: A History, Kevin Starr writes that California is perhaps “the most American of American places” and that it has long “become one of the prisms through which the American people, for better and for worse, could glimpse their future.” Starr, often called the dean of California historians, wrote this in 2005 and died in 2017—but his insight is perhaps most obvious today.

California’s long-brewing housing crisis is now a national phenomenon, and so is the mass homelessness that has been its inevitable consequence. For years, the state’s wildfires and heat waves have given Americans a vision of the country’s disastrous climate-change fate. Show business and Big Tech, having colonized the state’s political culture, have gone on to take over most everything. Meanwhile, the rest of the United States has grown to more closely resemble California in its visible diversity, as queerness, immigration status, and other forms of difference have become more legible in American public life.

In other words, California’s idiosyncratic political economy is becoming less idiosyncratic and more of a national condition. In some sense, this is nothing new: A broad array of American social realities, from widespread suburbanization to the peculiarities of post–New Deal radical politics, can trace much of their lineage back to California. But it has been a long time since developments in California have shaped the nation’s politics to such an extraordinary degree.

It is not surprising that Kamala Harris—the first California politician to lead a major party ticket since Ronald Reagan and the first-ever Democratic nominee from California—would carry her home state’s imprint. But both her running mate and the Republican ticket also tend to speak in distinctly Californian idioms. Each of the presidential and vice-presidential candidates is offering a California-inflected vision of the future, shaped by social crises and ideas that emerged out of the Golden State.

Current Issue

As a native of the state, Kamala Harris is, of course, the most Californian politician on either ticket; but at first glance, it can be challenging to pin down how this shapes her politics. The Harris campaign platform is largely a continuation of the Biden administration’s program; Harris has been careful to position herself as a Democratic unity candidate, not a representative of any faction or ideological tendency.

But she has taken sides in one of the most fervid intra-Democratic debates of the past 10 years, a debate that began in her own San Francisco Bay Area. This is the argument between anti-growth progressives and members of the YIMBY (“Yes in My Backyard”) movement.

San Francisco’s land-use system has long been hostile to any type of new development. As a result, the city has failed to add much housing stock even as its economy has boomed and created tens of thousands of high-wage tech jobs. This has led to one of the worst housing crises in the country, as affluent newcomers bid up the cost of a relatively fixed housing supply. Beginning in the mid-2010s, a group of activists calling themselves YIMBYs started to agitate for more housing supply, and for changes to local zoning and permitting rules that would make it easier to build. As similarly severe housing shortages have spread to other parts of the country—and to other anglophone countries like Canada, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia—the YIMBY movement has spread commensurately.

Harris gave a friendly nod to YIMBYs in her acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention when she promised to “end America’s housing shortage.” Even more revealing was her choice of Tim Walz for a running mate. As governor of Minnesota, Walz approved hundreds of millions in housing investments and even signed off on a bill to study legalizing single-staircase apartment buildings, a YIMBY priority that would lower the cost of apartment construction and allow more multifamily building on small parcels. He has even aligned himself with other YIMBY-inflected priorities beyond housing; for example, he signed a permitting reform bill intended to speed up the creation of renewable energy infrastructure. Most tellingly, during the vice-presidential debate, Walz repeatedly cited Minneapolis as a housing success story; the city comprehensively reformed its zoning and land-use rules in 2010 through the Minneapolis 2040 comprehensive plan, one of the most ambitious YIMBY initiatives implemented by any American city. Though Walz was not involved in the creation of the 2040 plan, he did sign a bill protecting it from legal challenges.

The evidence that the anti-growth politics of “neighborhood liberalism” contributed to the Bay Area’s housing crisis has led some California liberals and leftists to break from that tradition and return to something more like the industrious, pro-construction progressivism of the New Deal. A swing that parts of the Democratic Party are also making nationally.

Ad Policy

Factional conflict between YIMBYs and anti-YIMBYs in San Francisco is often vicious, but Harris has maintained friendly relations with both camps. (She even has a cordial relationship with Aaron Peskin, a long-standing enemy of the YIMBY movement and a current mayoral candidate.) Her commitment to representing the full spectrum of the Democratic Party is something she shares with the current president; Biden governed, at least domestically, as more of a progressive than his Washington centrist credentials would have suggested, in large part because he recognized that the Democratic Party’s center of gravity had shifted left since the Obama administration. But Biden brings a more backslapping approach to coalition-building, honed by his decades marinating in Senate collegiality. As her frequent references to her past as a prosecutor indicate, Harris has a harder edge.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

This combination—a catholic belief in Democratic unity and an utter ruthlessness toward people who aren’t willing to negotiate—is characteristic of politicians who manage to claw their way out of San Francisco and into higher office. It puts Harris in the company of Nancy Pelosi, and it betrays the influence of Willie Brown, the first Black man to become speaker of the California Assembly, the first Black man to become mayor of San Francisco, and Harris’s one-time political patron (and, briefly, her romantic partner).

What all these figures have in common is experience with some of the fiercest Democrat-on-Democrat warfare in the country. David Chiu, San Francisco’s city attorney, once described its politics as “a knife fight in a phone booth.”

There are two main reasons for the vituperative nature of San Francisco politics. The first is the city’s atmosphere of polycrisis: the combination of a housing shortage, mass homelessness, the fentanyl epidemic, and a dysfunctional public school system—to name just a few items on the city’s roster of current social disorders—has generated public anger and split San Francisco’s government into warring groups with different ideas about how to revitalize the city. And today’s San Francisco looks positively tranquil compared to the city of Brown’s early career—the San Francisco of Jim Jones, the Zodiac killer, the Zebra murders, Patti Hearst, and the assassinations of Harvey Milk and George Moscone.

The intensity of the political knife fight is exacerbated by the size of the phone booth. It’s not just that San Francisco, a global city with a smaller population than Indianapolis, doesn’t have enough housing for all its current residents; it also doesn’t have enough elected offices for all the political ambition that its wealth and cultural significance attracts. While there are plenty of lower-tier public offices for people just getting started on the cursus honorum—San Francisco has no fewer than 115 appointed commissions and boards—things start to get claustrophobic once all those commissioners seek out promotions. Because San Francisco is a combined city and county, the 11-person county board of supervisors acts as the city council; the city sends only one representative to the state Senate, two to the state Assembly, and one to Congress (unless you count the small chunk of the city that is in Representative Kevin Mullin’s district).

So anyone who wants to make the leap from local to state or federal politics needs to have the right friends, and they need to be willing to throw a punch. As Brown says in his memoir: “Don’t cross Willie Brown, don’t spit in the fountain of favors, because he certainly has more votes and moves than you do.” This is the school that produced Harris, and it gives us a sense of how she might govern as president. Most likely, President Harris would be pugnacious and highly competitive—while at the same time occupying the center-of-the-left space claimed by Biden.

The Republican ticket also has strong Bay Area connections through JD Vance. Vance embodies the hopes of Silicon Valley’s more fascism-curious billionaires: people like Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and investor David Sacks. Thiel, Vance’s former employer, gave $10 million to a pro-Vance super PAC ahead of the 2022 election that placed Vance in the Senate, and even personally introduced Vance to Trump. Musk and Sacks—along with San Diego native Tucker Carlson—urged Trump to pick Vance as his running mate.

The writer John Ganz has called their ideology “bossism,” borrowing from the language of apartheid South Africa. (Musk and Sacks are South African, while Thiel spent some formative years there.) As articulated at length by Curtis Yarvin, the chief theorist of neoreaction and self-described “dark elf,” their views are a flimsy latticework of political theory built to support the central belief of Silicon Valley’s authoritarian right: that as the best, most productive, smartest, and most genetically well-endowed people on earth, they deserve to rule—unshackled from government bureaucracy, worker power, or woke ideology.

The Bay Area’s housing crisis has helped fuel this authoritarian politics: As the limited housing supply has become more expensive, the shortage has transferred enormous amounts of wealth from tenants into the pockets of incumbent property owners. One of the results has been a chronic homelessness crisis, accompanied by a more ambient sense of social disorder. The failure of San Francisco’s progressive government to rein in the disorder, much less reverse it, has made reactionary alternatives look more appealing to some residents. This, in turn, has nurtured the autocratic tendencies of a faction in the tech elite.

This worldview has some resonances with the power-worshiping illiberalism of the Claremont Institute, based further to the south in the greater Los Angeles metropolitan area. That makes sense, as Claremont has attempted to build the intellectual spine (such as it is) of Trumpism through essays like Michael Anton’s “The Flight 93 Election” and Glenn Elmers’s “‘Conservatism’ Is Not Enough,” which went so far as to argue that 2020 Biden voters are an alien infection of the body politic. The Claremont Institute has also contributed a few of its own circle to Trump’s coterie, including Anton and John Eastman, who conspired with Trump in his efforts to remain in power following the 2020 election.

Moving our attention from Northern to Southern California helps us to better understand the top of the Republican ticket. While Trump comes from the world of New York real estate and tabloid culture, his political style bears some of the hallmarks of the political culture of the Southern Californian right.

The most obvious parallel is in how Trump collapses any distinction between the business of governing and the business of entertainment. Los Angeles, the Western capital of America’s culture industry, was the innovator here. It gave California two movie-star governors (Reagan and Arnold Schwarzenegger).

But while Trump shares with Reagan and Schwarzenegger a talent for transmuting celebrity into political power, he practices a very different kind of alchemy. Reagan leavened his far-right policy agenda with an appealingly sunny affect; Schwarzenegger, too, presented himself as an eternal optimist. Trump’s nastier, darker style has its roots in a different tradition.

This tradition infuses a showman’s approach to monopolizing public attention with the anxieties of a white, status-conscious, suburban middle class. One of its earlier practitioners in Southern California was Howard Jarvis, the architect of Proposition 13, which in 1978 put a low ceiling on California’s property taxes. Like Trump, Jarvis was a carnival barker who played on the resentment of the white petite bourgeoisie against government bureaucrats and welfare moochers. (It helped that property tax bills for a lot of middle-class homeowners across the state really could be quite onerous.) In Reaganland, the historian Rick Perlstein depicts Jarvis, who died in 1986, as a habitual grifter and quotes a journalist who called him an “angry muppet.” Sound familiar?

Driven by fear of the state’s changing demographics—California became less than 50 percent white around the turn of the millennium—Southern Californian conservatives also helped lay the foundation for contemporary immigration politics. As with the tax revolt, Southern California’s anti-immigrant backlash was fueled in part by economic conditions on the ground: Like the Midwestern states where Trump overperformed in 2016, the Southern California of the 1990s had been absolutely hammered by deindustrialization. The main culprit in the latter case was not NAFTA but the end of the Cold War, which decimated the region’s defense industry. The late Mike Davis wrote that when demographic change coincided with the loss of Southern California’s manufacturing base, it “opened up a Pandora’s box of bigotry and white anger.”

In 1994, Governor Pete Wilson, the former mayor of San Diego, championed Proposition 187, which would have set up an intrusive (and, according to the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, inefficient) screening process to deny undocumented immigrants access to public services like schooling and medical care.

The measure passed, but the courts voided it, and it was eventually repealed. Nonetheless, Trump has adopted Prop 187–style politics as the ideological core of his movement: both in the vicious, eliminationist language that Prop 187 supporters would deploy against undocumented Latino immigrants and in the welfare chauvinist philosophy of close advisers like Stephen Miller, who was 9 years old and living in Santa Monica at the time of the Prop 187 campaign.

More on California politics:

But if anyone provides a clear link between the Southern Californian right and Trump, it is Andrew Breitbart, the late founder of breitbart.com. Breitbart combined the apocalyptic style of post-Reagan conservatives like Pat Buchanan with an understanding of how to manipulate an information environment shaped by cable news and online media.

Breitbart grew up in the shadow of Hollywood and launched his career on the right by fulminating against left-wing bias in the American film industry. He created his own little media empire as an alternative base of culture production. In his book Righteous Indignation, he summarized his theory of power this way: “In the twenty-first century, media is everything. The left wins because it controls the narrative. The narrative is controlled by the media. The left is the media. Narrative is everything.” Right-wingers have complained about the media’s liberal bias for decades, but Breitbart—saturated in the culture of a place where entertainment is the largest industry—was unusual in his single-minded fixation on gaining and holding attention as its own end.

If narrative is everything, then controlling the narrative is more important than setting policy, appointing government personnel, or even winning elections. So Breitbart set out to create a new narrative. And while he died in 2012, his acolytes fill the ranks of the MAGA media, with Steve Bannon and Ben Shapiro serving as perhaps the most prominent examples. His brand of post-materialist white identity politics is now the mode of the Republican Party’s most powerful faction.

In other words, the social and material developments that have shaped California politics are much like those shaping the country as a whole—only more so. There is a lesson there for the left, and a warning, if we care to heed it. Government dysfunction in California has long succored reactionary politics, from the burdensome property tax assessments that inspired Proposition 13 to the broken land-use regime in Silicon Valley’s backyard. If the political coalition in favor of liberal democracy cannot govern effectively and prove itself capable of addressing crises like the housing shortage, then they will only make illiberalism look even more seductive.

Can we count on you?

In the coming election, the fate of our democracy and fundamental civil rights are on the ballot. The conservative architects of Project 2025 are scheming to institutionalize Donald Trump’s authoritarian vision across all levels of government if he should win.

We’ve already seen events that fill us with both dread and cautious optimism—throughout it all, The Nation has been a bulwark against misinformation and an advocate for bold, principled perspectives. Our dedicated writers have sat down with Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders for interviews, unpacked the shallow right-wing populist appeals of J.D. Vance, and debated the pathway for a Democratic victory in November.

Stories like these and the one you just read are vital at this critical juncture in our country’s history. Now more than ever, we need clear-eyed and deeply reported independent journalism to make sense of the headlines and sort fact from fiction. Donate today and join our 160-year legacy of speaking truth to power and uplifting the voices of grassroots advocates.

Throughout 2024 and what is likely the defining election of our lifetimes, we need your support to continue publishing the insightful journalism you rely on.

Thank you,

The Editors of The Nation

[ad_2]