[ad_1]

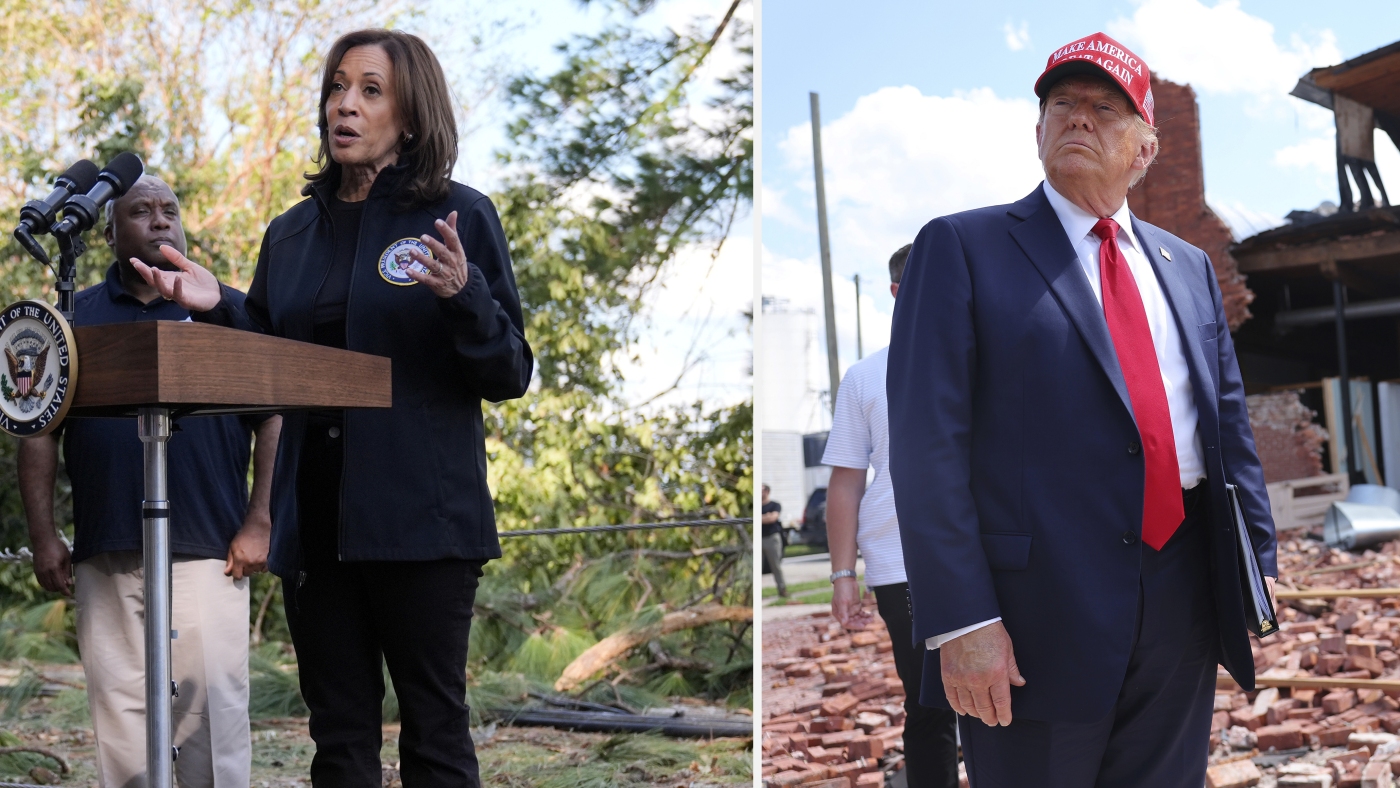

Both presidential candidates visited Georgia after Hurricane Helene: Vice President Harris in Augusta on Oct. 2 and former President Trump in Valdosta on Sept. 30. Trump has tried to weaponize the federal response to the storm.

Carolyn Kaster/AP; Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Carolyn Kaster/AP; Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Election season and Atlantic hurricane season always overlap on the calendar. And this year, they’re coming together to form quite the political storm.

First came Helene, which hit Florida as a Category 4 hurricane before drenching a deadly path across several southeastern states. The late September storm killed more than 230 people, flooded entire communities and destroyed critical infrastructure, particularly in hard-hit western North Carolina.

As the road to recovery begins, the federal government’s response has been hampered by considerable politicization and misinformation, mostly online.

While some Republicans have praised the Biden administration’s response, many others — most notably, former President Donald Trump — are seeking to weaponize it against his presidential opponent, Vice President Harris.

On rally stages and social media platforms like X, they have accused local governments of preventing private citizens from helping people in need and alleged that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has no money for hurricane recovery because of spending on migrants and foreign wars (none of these claims are true).

“We absolutely have the funding that we need to support the ongoing response to Helene and the response that we’re preparing for Hurricane Milton,” FEMA administrator Deanne Criswell told NPR’s Morning Edition on Tuesday.

She called the misinformation around the storm “absolutely the worst I have ever seen,” telling reporters on a separate call Tuesday that the conspiracy theories — which the agency has set up a webpage to debunk — are dissuading survivors from seeking help and hurting responders’ morale.

Against this backdrop, federal and state authorities are preparing for Hurricane Milton, an unusually fast-growing storm poised to bring a life-threatening storm surge and winds to Florida midweek.

That has fueled further political drama, with NBC News reporting on Monday that Florida’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis — whose response to several major hurricanes in 2022 partially helped him win a second term that year — refused to take Harris’ calls about hurricane relief. He has spoken to President Biden.

DeSantis denied the reports about Harris’ calls, and each has since publicly accused the other of playing “political games.”

So how much of an impact could these hurricanes — and the candidates’ responses — have on the upcoming presidential election?

The widespread destruction and displacement as a result of Helene could significantly disrupt the voting process in the key swing states of Georgia and North Carolina, where election officials are changing rules and making plans in the hopes that all eligible residents will still be able to vote, either by mail or in person.

But how — and whether — voters impacted by the storm fill out their ballots remains to be seen. In the meantime, here’s a look at some of the major hurricanes that have shaped elections in recent years.

2005: Hurricane Katrina

President George W. Bush looks out the window of Air Force One on August 31, 2005, as he surveys Hurricane Katrina damage over New Orleans on his way from Texas to Washington, D.C. The photo and flyover were widely panned, and he later called them a mistake.

Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images

Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall in southeast Louisiana on Aug. 29, 2005, was one of the most destructive in U.S. history, causing more than 1,800 deaths and some $125 billion in damage.

The painful aftermath of the storm was exacerbated by a series of bureaucratic failings, from poor communication between state and federal leaders to partisan fighting over federal relief for New Orleans to what is widely regarded as an embarrassingly too-little-too-late response by then-President George W. Bush and his administration.

Critics of Bush slammed him for initially ignoring the storm to continue a previously planned vacation at his Texas ranch and releasing now-infamous photos of himself surveying the damage from Air Force One en route back to Washington, D.C.

Bush went on to face further criticism for delaying visits to affected areas and heaping what many considered undeserved praise on FEMA Director Michael Brown (“Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job,” was Bush’s much-criticized quote, uttered while thousands were sheltering without food or water in the Superdome)

But those early photos stood out to many Americans as a symbol of his detachment from the crisis. Bush himself acknowledged years later that they made him look “detached and uncaring,” calling the flyover a “huge mistake.”

“I should have touched down in Baton Rouge, met with the governor and walked out and said, ‘I hear you. We understand. And we’re going to help the state and help the local governments with as much resources as needed,’ ” Bush told NBC in 2010. “And then got back on a flight up to Washington. I did not do that. And paid a price for it.”

The fallout from Katrina — as well as the turning tide of public opinion against the Iraq War — sent Bush’s approval ratings to new lows, from which he never recovered. He left office in 2009 with an approval rating of 24%, according to Pew Research Center.

Since the tragedy unfolded just a year into Bush’s second term, it had no immediate electoral consequences. But lessons from that disaster informed how he and his successors responded to major hurricanes in the years that followed.

2008: Hurricane Gustav

First Lady Laura Bush (R) and Cindy McCain (L) fundraised for Gustav relief efforts on the first day of the Republican National Convention in St. Paul, Minnesota, in September 2008.

Paul J. Richards/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Paul J. Richards/AFP via Getty Images

Hurricane Gustav touched down in southeast Louisiana as a Category 2 storm on Sept. 1, 2008 — the first day of the Republican National Convention in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Presidential nominee Sen. John McCain traveled to the Gulf Coast ahead of the storm’s landfall. And, with an eye to the optics of holding a political celebration during a natural disaster, he instructed the GOP to cancel most of the convention’s first-day events. They cut the programming down from seven hours to two-and-a-half.

“We will act as Americans, not as Republicans, because America needs us now, no matter whether we are Republican or Democrat,” McCain said, as NPR reported at the time. “And America needs all of us to do what Americans have always done in times of disaster and challenge, and that is join together and help our fellow citizens.”

Opening speeches by then-President Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney were scrapped, and the two ultimately canceled their trips to Minnesota to focus on relief efforts. Bush later addressed the convention via satellite instead.

Gustav dominated the scaled-back convention, at least at first.

First lady Laura Bush and Cindy McCain urged people to donate to relief efforts in their opening-day speeches, and hundreds of fans and delegates gathered that night for a “Fiesta America” charity concert for Gulf relief efforts, headlined by Daddy Yankee.

The Republican National Committee was also quick to criticize Democratic nominee Barack Obama, who shortly afterward swapped his stump speech for a plea for Red Cross donations on the campaign trail.

But the hurricane’s impact on the election itself appears to have been minimal. Despite the criticism, Obama went on to win.

That wasn’t the last time a hurricane has coincided with a nominating convention: Tropical Storm Isaac forced Republicans to cancel some of their events in August 2012, while Hurricane Laura came ashore in Louisiana on the day of Trump’s acceptance speech at the 2020 RNC (he visited FEMA for a briefing hours before).

2012: Hurricane Sandy

President Barack Obama (R) is greeted by New Jersey Governor Chris Christie upon arriving in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on October 31, 2012 to visit areas hit by Superstorm Sandy.

Jewel Samad/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jewel Samad/AFP via Getty Images

After making landfall in Haiti and the Bahamas in late October 2012, Hurricane Sandy — also known as Superstorm Sandy — turned toward the East Coast with a vengeance.

The storm made landfall near Brigantine, N.J., on October 29. It brought significant flooding to the entire Eastern seaboard, particularly parts of New Jersey and New York, and caused some $70 billion in damages.

Sandy hit exactly a week before the presidential election, as incumbent President Barack Obama and Utah Sen. Mitt Romney were making their final push to voters (they both stopped campaigning after the storm).

Obama’s response to the storm drew praise at the time, including from New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, a Republican, a Romney surrogate and a vocal critic of the then-president.

The two were filmed warmly shaking hands as Obama arrived on a New Jersey tarmac to survey hurricane damage. The images of that scene, less than a week before Election Day, were seen by some as an enduring image of bipartisanship.

It didn’t land well with some Republicans, however. Their embrace (or as Christie later called it: “the old, ‘nobody-ever-saw-it-because-it-didn’t-happen’ hug”) was even used against Christie in a 2016 attack ad by a conservative group backing one of his primary challengers.

While many supporters saw Obama as rising to the challenge posed by Sandy, the storm also drew attention to a potential weak spot of Romney’s.

Romeny had said earlier at a primary debate that, as president, he would support shuttering FEMA and leaving disaster relief to the states. But after Sandy hit — and Romney dodged several opportunities to clarify his stance — his campaign released a statement affirming support for FEMA funding after all.

Days later, Obama won reelection.

Polls from 2012 show that Obama led in votes from people who decided who to vote for within three days of the election, which could point to support for his handling of Sandy. In another, clearer sign, 15% of the electorate rated his hurricane response as the single most important factor in their vote.

2017: Hurricane Maria

President Trump tosses paper towels into a crowd at Calvary Chapel in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, during a post-Maria visit in October 2017.

Evan Vucci/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Evan Vucci/AP

Hurricane Maria slammed into Puerto Rico on Sept. 20, 2017. While it wasn’t an election year, the ramifications of the storm persisted long after.

Maria wiped out roads, flattened buildings and destroyed the island’s entire power grid, leaving some 3.4 million residents in the dark.

That would go on to become the longest blackout in U.S. history, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, with the last remaining households only getting power back in mid-August 2018. The island’s infrastructure is still recovering seven years later.

Many criticized the disaster response as slow, insufficient and disorganized, especially considering the high poverty rate and lack of disaster preparedness infrastructure on the island, which is a U.S. territory (meaning its residents cannot vote directly in presidential elections).

Even FEMA acknowledged in a 2018 report that it had failed to provide adequate support to hurricane victims in Puerto Rico and other areas, pointing to issues including a lack of key supplies in place before the storm, underqualified and understaffed teams and challenges with communication and delivering emergency supplies.

Several other reports from U.S. agencies would later add credence to the widely-held perception of neglect by the federal government.

A Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Inspector General report released in 2021 confirmed that the Trump administration withheld some $20 billion in hurricane relief Congress approved for Puerto Rico, then blocked an investigation into that inaction.

The following year, a U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report that found the speed and scale of federal spending for Maria paled in comparison to that for Hurricane Harvey, which hit Texas the same year.

Trump himself repeatedly opposed aid to Puerto Rico while in office, reportedly told aides he did not want a “single dollar” going there and denied and downplayed the death toll of 3,000 from hurricanes Maria and Irma.

And when he visited the island several weeks after Maria, he was roundly criticized for tossing paper towel rolls into a crowd of people at a relief center (“like they were free T-shirts at a sporting event,” NPR wrote at the time).

Maria underscored significant disparities and shortcomings in the federal government’s disaster response. In the years since, it has informed the votes of displaced Puerto Ricans who have moved to the mainland U.S. — including the key state of Pennsylvania.

2018: Hurricane Michael

Voters walk through debris to vote in a new polling location after their regular polling place was damaged by Hurricane Michael in Wakulla Country, Fla., in November 2018.

Mark Wallheiser/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Mark Wallheiser/Getty Images

Hurricane Michael hit the Florida panhandle on Oct. 10, 2018, less than a month before Floridians were due to cast their votes for governor and U.S. senator, two roles with both local and national significance.

The storm directly impacted both races, as Steve Bousquet, then the Tallahassee bureau chief for the Tampa Bay Times, told NPR at the time.

Andrew Gillum, the Democratic candidate for governor, was the mayor of hard-hit Tallahassee, while the leading Republican U.S. Senate candidate was Rick Scott, the sitting governor tasked with helping the state recover.

“What a hurricane does to alter the dynamics of politics and campaigning is it reinforces to people that without government, you have nothing in an emergency,” Bousquet said.

Gillum lost his race to DeSantis, while Scott won his. But another major takeaway from the election was the low voter turnout in hard-hit areas.

The governor issued an executive order aimed at making it easier for people to vote by loosening voting laws and consolidating polling locations in the eight counties most affected by the storm. But experts say that the order actually made it harder for people to vote in person, by closing many planned polling locations without providing funding to open up new ones.

A 2022 University of Chicago study published found a 7% decline in voter turnout in the eight most-impacted counties, which it attributes mostly to the fact that people had to travel farther to vote after polling places closed.

Co-author Kevin Morris, a quantitative researcher with the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program at New York University, told member station WUSF that year that the paper estimated more than 13,000 ballots went uncast because of the hurricane.

“In 2018, the Senate race was decided by just over 10,000 ballots,” he said. “So if the hurricane depressed turnout by 13,000, that is a really big magnitude.”

Morris said voting may understandably be a lower priority for people who have just survived a major hurricane and are struggling to meet their basic needs. But he also said the state is responsible for protecting their right to do so.

“The key question needs to be how do they keep polling places open?” he said.

It’s a question that’s come up again and again in the years since Michael struck and DeSantis took office, from Hurricane Ian in 2022 to Helene today.

[ad_2]