[ad_1]

Maggie Billiman, left, and sister Julia Billiman Torres, lead Virginia Chavez, left and Mary Martinez White to a meeting to push for reauthorization of the Radiation Compensation Exposure Act.

Claudia Grisales/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claudia Grisales/NPR

Maggie Billiman, left, and sister Julia Billiman Torres, lead Virginia Chavez, left and Mary Martinez White to a meeting to push for reauthorization of the Radiation Compensation Exposure Act.

Claudia Grisales/NPR

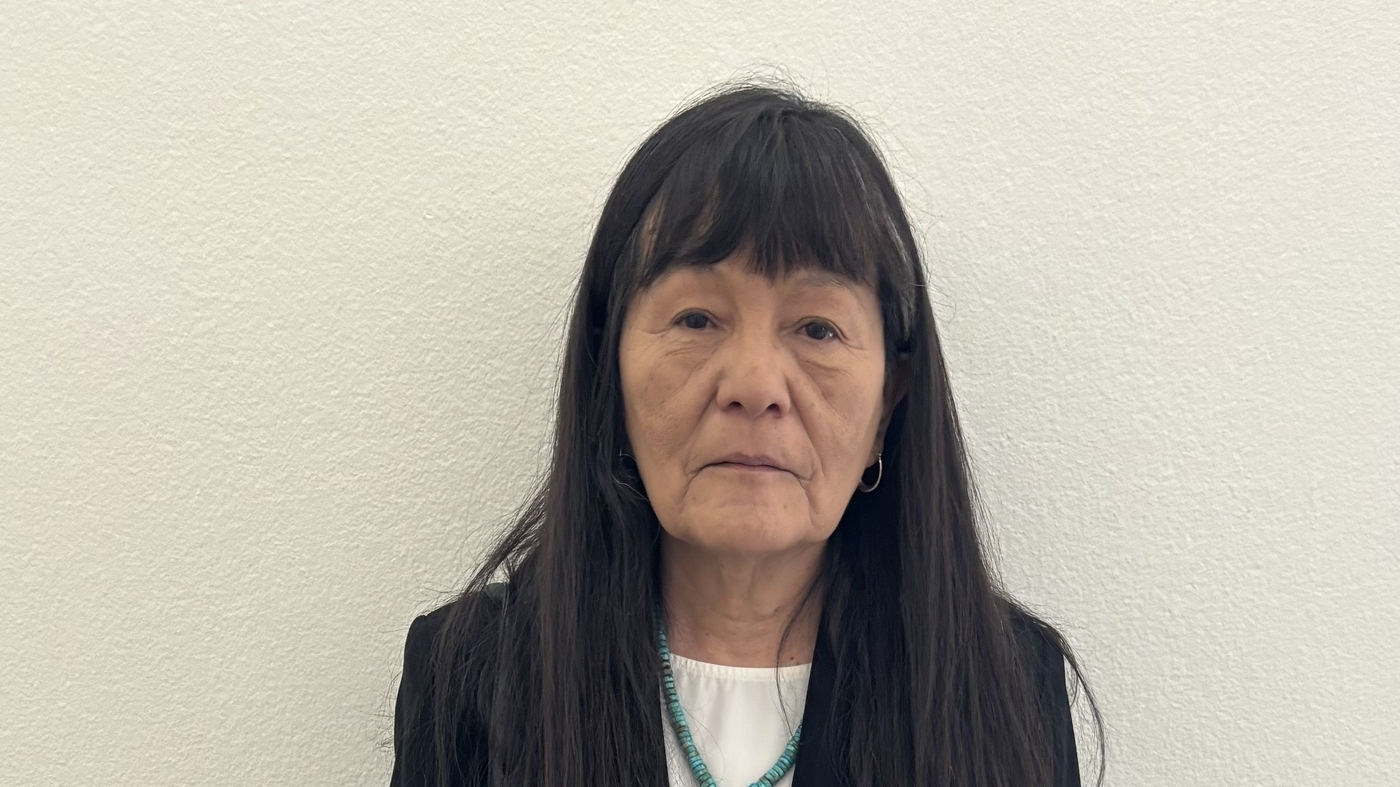

Between meetings in a busy congressional hallway, a tearful Maggie Billiman tightly gripped a picture of her late parents.

The 63-year-old tribal member worried her visit to the Capitol this week would mark her last chance to fight for families sickened by the nation’s nuclear testing program.

“I just want to make sure that these leaders hear us,” an emotional Billiman told NPR. She traveled to Washington from Navajo Nation despite ongoing thyroid and pancreatic illnesses.

Billiman is joining about two dozen advocates on Capitol Hill this week to fight for the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, or RECA. The 34-year-old federal program is set to expire on June 7th, removing a lifeline for the so-called atomic veterans, downwinders and more.

Their push includes visits to dozens of House lawmakers’ offices to tell their stories one by one in hopes of spreading the word that time is running out. On Thursday, they’ll join a key group of lawmakers, including Sens. Ben Ray Luján, D-N.M., and Josh Hawley, R-Mo., for a press conference pushing to save RECA.

Billiman’s late father, Howard, was a World War II Navajo code talker for the U.S. Marine Corps. He later died of stomach cancer, part of a long list of illnesses for the family.

Billiman relayed her story in a closed-door meeting with a congressional staffer.

Sisters Maggie Billiman, left, and Julia Billiman Torres, lead Virginia Chavez, left and Mary Martinez White to lobby members to reauthorize the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act.

Claudia Grisales/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claudia Grisales/NPR

Sisters Maggie Billiman, left, and Julia Billiman Torres, lead Virginia Chavez, left and Mary Martinez White to lobby members to reauthorize the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act.

Claudia Grisales/NPR

“My family is dying and we’re all getting cancer left and right,” she said.

In the past year, the Senate approved multiple bipartisan bills sponsored by Luján and Hawley to reauthorize and expand the RECA program. However, the bill stalled out in the House, where some Republicans object to its cost.

The plan’s sponsors argue that’s been addressed by reducing a 2023 estimate of $143 billion down to $50 billion to $60 billion.

“Thousands of Americans will lose …lifesaving help” if lawmakers fail to act, Hawley recently told NPR.

Luján, who has filed legislation to expand the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act annually since 2008, hopes this isn’t the year it expires.

A complicated history with a new spotlight

Since its enactment in 1990, RECA has provided lump sum payments of up to $75,000 to atomic veterans and others sickened by the nuclear testing program. In all, the Justice Department program has disbursed $2.7 billion in payments to more 40,000 recipients.

The Oscar-winning film of the year, Oppenheimer, spotlighted the Manhattan project, but lawmakers worry the film’s attention may not be enough.

New Mexico resident Mary Martinez White, 66, is one of the advocates hoping their trip to Capitol Hill his week will finally win over support from House Speaker Mike Johnson. Martinez White grew up in a community 45 miles from the site of the first atomic bomb test.

Maggie Billiman holds a picture of her late parents, Mary Louis and Howard Billiman. She believes her father died of cancer related to his exposure to nuclear fallout.

Claudia Grisales/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claudia Grisales/NPR

Maggie Billiman holds a picture of her late parents, Mary Louis and Howard Billiman. She believes her father died of cancer related to his exposure to nuclear fallout.

Claudia Grisales/NPR

“This is our last opportunity before the sunset to win over Mike Johnson and others — especially Mike Johnson,” she said. “We are hoping that he will have a heart and not betray his fellow patriots like we’ve been betrayed in the past.”

Martinez White is a member of a group known as the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, which is raising awareness of illnesses tied to Trinity, the code name for the first nuclear bomb test in 1945.

She blames the test’s fallout for a half of dozen cases of cancer in her family of 10. Martinez White and at least another half dozen relatives are also suffering from thyroid-related illness.

“I would often go home for funerals and everybody in Tularosa was dying of cancer. We knew something was very weird,” she said. “There’s no industry in the whole Tularosa Basin but for White Sands Missile Range, where the Trinity bomb was detonated.”

[ad_2]

Victor osuhon

Interesting