[ad_1]

And the Supreme Court may be about to make the situation worse.

Police misconduct continues to be among the nation’s biggest public problems, putting Black Americans especially at risk every day. The policy tools to tackle this problem range from strengthening the powers of federal investigation and criminal prosecution to more comprehensive structural changes such as defunding and abolition. But in the absence of such public reforms, private civil rights lawsuits remain essential to holding cities and officers accountable. Those suits already are an uphill battle for people injured at the hands of the police. But the climb may soon get steeper for an unexpected reason.

Cities have been using the American bankruptcy system to shield themselves from liability for police misconduct. Although those cases have been rare so far, the United States Supreme Court is set to rule any day on a case that could make bankruptcy an even more formidable barrier to accountability for excessive force and other wrongs. The practical effect would be to chill civil rights lawyers from even trying to enforce victims’ rights in cities where police reform is most needed.

Most bankruptcy filers are individual people, with companies in a distant second place. But cities, as “municipalities,” also are eligible under some circumstances. Bankruptcy law makes it possible to change all creditors’ rights without obtaining consent from each and every one. The bankruptcy system’s doors initially opened to governments in the 1930s so they could reset the repayment schedules for municipal bonds they’d issued.

Current Issue

Fear of a New York City collapse prompted Congress to give municipal bankruptcy filers a bigger toolbox in 1976. An even broader overhaul of the American bankruptcy system in 1978 allowed all kinds of cases to change the rights of more claimants than ever before—including people alleging injury, whether or not they had filed or prevailed in lawsuits. Bankruptcy law treats allegations of police brutality—a bodily harm rooted in constitutional rights—the same way it treats an invoice for office supplies or credit card debt.

Civil rights obligations do not drive big cities into bankruptcy. According to professor Joanna Schwartz, a leading expert on police misconduct liability, civil rights judgments typically constitute less than 1 percent of local budgets. Instead, the big issues tend to be the inability to honor the terms of municipal bonds and other financial instruments and underfunded public pensions. When a case is centered on reworking obligations like bonds and pensions, cities offer no seat at the negotiating table to injured individuals, whether they have been hit by a city bus or subject to police abuse. Canceling civil rights liabilities has become an incidental “benefit” of bankruptcy, even if unnecessary for economic recovery.

A decade ago, the City of Detroit used federal bankruptcy law to cut $7 billion in debt. The breadth of modern bankruptcy law made it possible for Detroit—a majority-Black city with a long history of police problems—to change the rights of people who had alleged police misconduct and other civil rights violations. Detroit promised civil rights claimants a low level of compensation (just 10–13 percent of their claims)—a payment level that sunk to pennies on the dollar in the years after a court approved the city’s plan. Claimants who didn’t file the proper paperwork couldn’t recover at all.

Notably, Detroit’s civil rights claimants retained important rights because the court denied the city’s request to use its bankruptcy to shield police officers of their own personal liability. Detroit remained on the the hook to pay those judgments under collective bargaining agreements with the police.

Depending on the outcome of the pending Supreme Court case, civil rights claimants in other cities won’t get to retain those rights. The question in the Supreme Court case is whether an entity can use its own bankruptcy to permanently shield third parties that have not filed for bankruptcy themselves. In the case before the Supreme Court, the bankruptcy filer is OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma, and the protected parties are the wealthy Sackler family. But if the highest court greenlights Purdue Pharma’s plan, cities contemplating bankruptcy are more likely to seek liability shields for their police officers.

The risk is not hypothetical; police officers in the City of San Bernardino, California, got protection from that city’s bankruptcy in 2016. How much compensation for the loss of their civil rights did claimants against the city and the officers end up getting? One penny on the dollar.

The Supreme Court ruling also could affect people alleging wrongdoing by officers in the City of Chester, Pennsylvania, currently in bankruptcy. Again, police misconduct problems did not drive Chester into bankruptcy, but Chester has racked up settlements, judgments, and more lawsuits relating to its choke hold practices that could be permanently affected by the case.

To be sure, many police misconduct victims cannot win lawsuits whether or not the city enters bankruptcy. An expansive interpretation of the controversial doctrine of qualified immunity already leads many lawsuits to get tossed. Over the years, courts have explained that civil rights law’s checks and balances are necessary to protect local government finances and to prevent chilling police officers in the line of duty.

But even if we accept that rationale, it hardly justifies bankruptcy offering a supplemental legal and financial shield. Bankruptcy becomes a layer of unqualified immunity unplanned by policymakers.

Ad Policy

If the Supreme Court authorizes protecting third parties through another party’s bankruptcy, the ruling could encourage cities to use police brutality as a bargaining chip. Cities that need to cut compensation or benefit packages can offer police officers insulation against responsibility for misconduct as a concession.

The bigger-picture impact is to undercut the primary mechanism in our current—and far from perfect—legal system to enforce the constitutional rights of people, particularly Black Americans, harmed by the police: private, and privately funded, litigation. Financial compensation, said the US Supreme Court once upon a time, would help vindicate “cherished constitutional guarantees” and serve “as a deterrent against future constitutional deprivations.” Although injured people bring lawsuits for nonfinancial reasons, the reward of money is key to ensuring that experienced lawyers can invest considerable time and resources in the case. In other words, if governments can use bankruptcy to insulate themselves and their officers from civil rights liability, bankruptcy could deter accountability in the very cities that need it most.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish every day at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

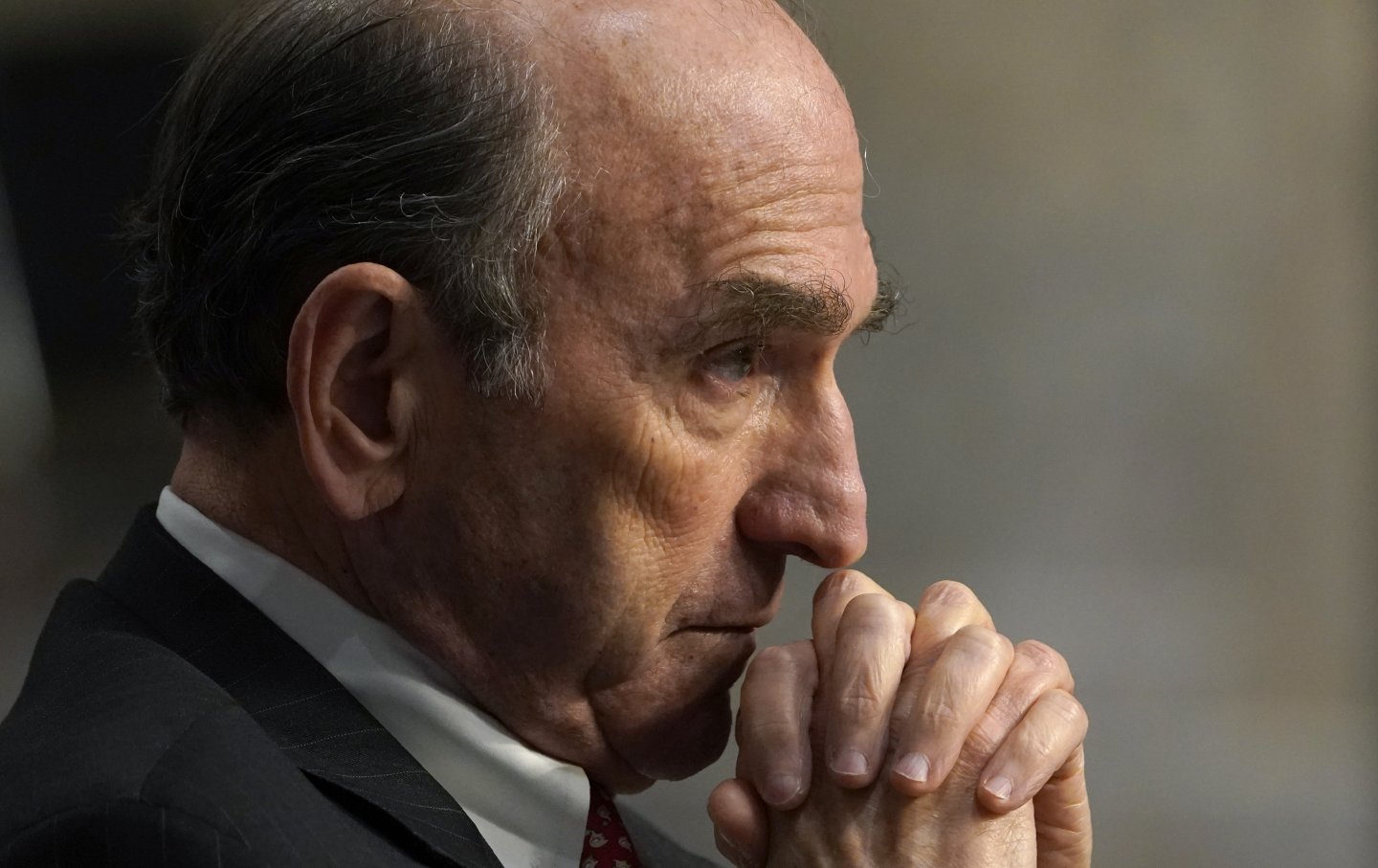

A career nearly as steeped in blood as Henry Kissinger’s hasn’t prevented the establishment from embracing—and whitewashing—this serial slanderer.

Eric Alterman

The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act protects workers who need to take time off to have an abortion. But now a Louisiana judge has eliminated that provision for anyone living in Missi…

Bryce Covert

Administrators announced the closure with little warning on May 31. “It was like a slap in the face or a punch in the gut. It just didn’t feel real.”

StudentNation

/

Lucy Tobier

When the “Race to the Top” becomes winner take all, students are the big losers. And as the stakes grow higher and higher, public education falls further behind.

Feature

/

Jennifer C. Berkshire and Jack Schneider

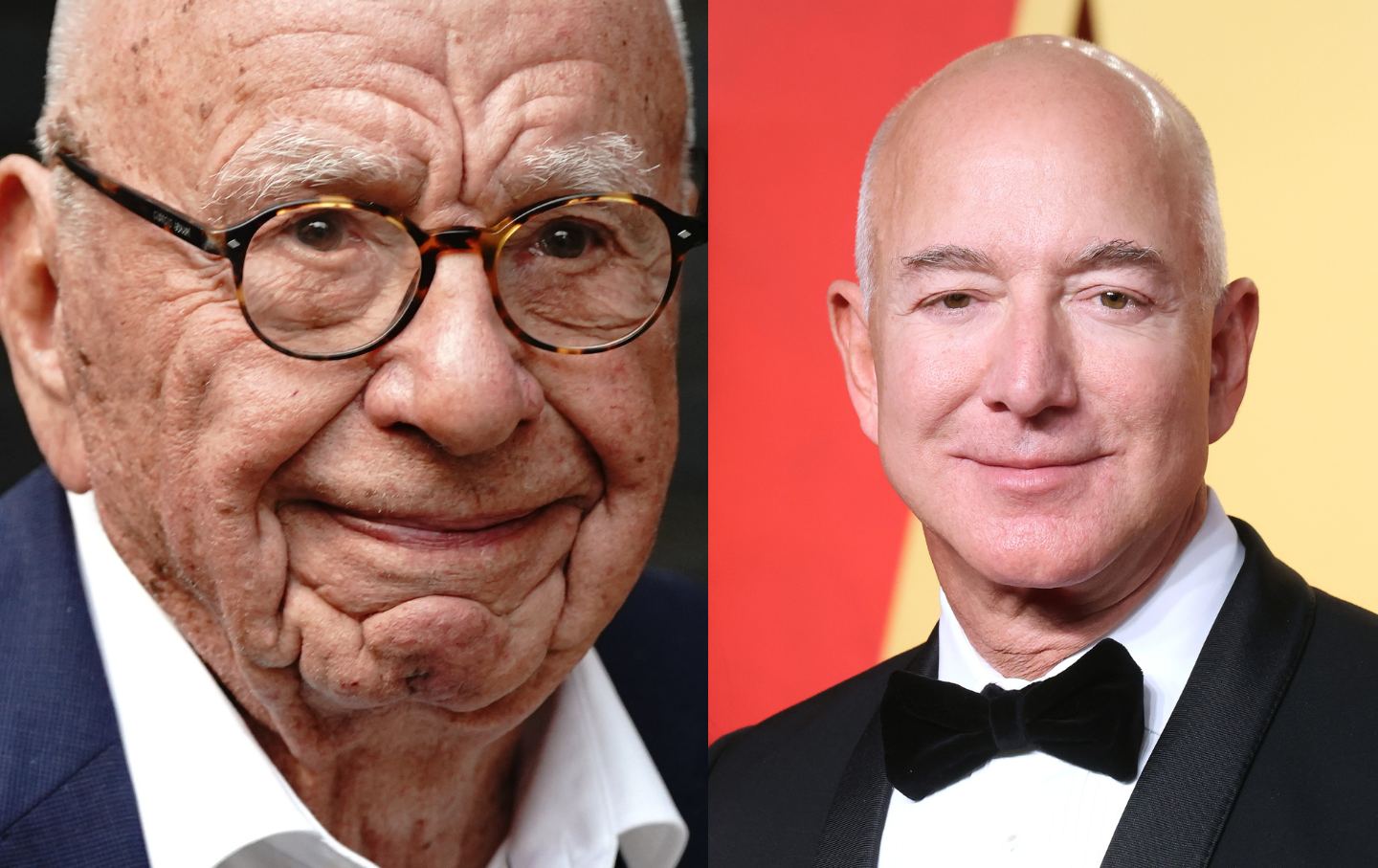

The Washington Post is now run by a master of squalid tabloid journalism.

Jeet Heer

This is the only possible conclusion after their decision striking down the federal ban on bump stocks.

Elie Mystal

[ad_2]