[ad_1]

The art world has begun its unofficial fall semester, and as much as I love a good syllabus, I’ve never been more grateful to be able to choose my own readings. Several new books and writing coming out this season give us stirring ideas to look forward to, from Didi Jackson’s poetry after Hilma af Klint to a newly translated Sophie Calle book. Some titles pair well with older books, with contributor Bridget Quinn recommending a memoir by Manjula Martin to accompany Obi Kaufmann’s A State of Fire. I hope to re-read critic Hettie Judah’s short 2023 book chock full of interviews with artist-parents before diving into her new release, On Art and Motherhood. Titles on the visual language of occult traditions across time, a fictionalized account of art patron Peggy Guggenheim’s life, propaganda posters from around the world, Sonya Kelliher-Combs’s metamorphic sculptures, and more promise captivating reads to be challenged and changed by. —Lakshmi Rivera Amin, Associate Editor

Bound Up: On Kink, Power, and Belonging by Leora Fridman

This book begins, “Like many a nice Jewish girl, I begin in Hebrew class,” but what follows is my impressionist take — not an exhaustive list — on the author’s literary journey in 240 pages. First stop, generational trauma (same, Leora, same), then onward to a network of other themes: racialization and minoritization (a theme that suffuses the book and offers some of the most astute writing), her relationship to Israel (timely, and you got my attention), kink with a German (let me grab my popcorn), illness and shame (yes, I’ll have that gummy and maybe a little cry), insomnia (oof, feeling this deeply), Nazi furries and shame (how did I get here; but I’m so committed now), reflections on looking at people’s pets (so many thoughts), role-playing and BDSM (a favorite leitmotif), being an American in Berlin (explaining The Sound of Music to Germans is funny), the afterlives of the Holocaust (relatable, and her takes feel informed by a lot of contemporary research which makes them feel particularly poignant), diasporic ruminations (straight into my veins!), reflections on nudity (mostly wholesome and thought-provoking), repeated visits to various art exhibitions (some more interesting than others, but clearly coming from a place of love), her take on Ginuwine’s “Pony” in the Magic Mike franchise (unexpected and meaningful), thoughts of her partner’s cremaster (touching and sweet), and then the Matthew Barney series (the self-consciousness of looking is key here and helps ground the book in ideas around spectatorship). And the art hipster milieu of Berlin, an exile city, permeates throughout, as do thoughts about fascism — how could they not?

Fridman’s writing is full of observations that tend toward essayism rather than more austere criticism. She discusses writers and thinkers such as bell hooks, Sarah Schulman, Saadiya Hartman, Hannah Arendt, Chris Krauss, and many others. You feel Fridman’s body walk through spaces, which is the type of embodied criticism I tend to enjoy most. At one point she writes, “When people fix things … they want the broken things to be gone… repair can erase memory, whether we are thinking about a precious broken cup or a crime.” Fridman is not repairing anything, but sometimes I’m not sure she isn’t. This book succeeds in that ambiguity. —Hrag Vartanian

Buy on Bookshop | Wayne State University Press, September 2024

Seeing Baya: Portrait of an Algerian Artist in Paris by Alice Kaplan

Self-taught Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine has been getting more attention than ever, and her personal story is part of the reason we can’t get enough of her. While her art is vibrant and eludes easy characterization, her story is the stuff of legend in our biography-obsessed age. Orphaned at the age of five and then raised by her grandmother, she was adopted by a French woman in Algiers who would force the young Mahieddine to perform household duties, while allotting her art supplies to pursue her fast-growing visual talents. Mahieddine had her first Paris show at the age of 16, a rarity for a female artist, never mind a North African one, and renowned Surrealist André Breton wrote the preface to her first catalog. She would later join Pablo Picasso to work on some of his pottery. If you think this is enticing, then you’ll love this volume that tells her story, which intersects with what feels like every sphere of French intellectual life in the 20th century. —HV

Buy on Bookshop | University of Chicago Press, October 2024

Mark: Sonya Kelliher-Combs, edited by Julie Decker

I’ve never encountered an artist who explores the topics of sexual abuse and suicide with the visual sensitivity of Anchorage-based Iñupiaq and Athabaskan artist Sonya Kelliher-Combs. Cruel realities are rendered into incredibly complex, emotionally charged objects of contemplation that resist categorization but draw us in by providing clues that slowly reveal their histories. Sleeves are transformed into elegant tubes, parka toggles are like secrets in a bottle, and mittens become symbols of interiority that leave their mark on our consciousness. Edited by Julie Decker, the director of the Anchorage Art Museum, the exhibition catalog includes an extensive interview with curator Candice Hopkins. Essays by artist Tanya Lukin Linklater, art historian Heather Igloliorte, and curator Laura Phipps complete the volume, along with poems by Taqralik Partridge and numerous images of the artist’s drawings, paintings, sculptures, and installations. A pure joy of creativity. —HV

Buy on Bookshop | Hirmer Publishers and Anchorage Art Museum, October 2024

The Sleepers by Sophie Calle, translated by Emma Ramadan

In April 1979, French conceptual artist Sophie Calle offered her bed to strangers. It’s not what you think: She invited 27 individuals to each sleep in her bed for eight hours as long as they agreed to be watched, photographed, and answer a few questions. The result was an exhibition later that year presenting 198 photographs of the “sleepers” in various positions in Calle’s bed, collaged with brief texts describing what went on in their heads. This lovely book, promised to be “clothbound and pillow-like” when it’s released in November, is an expanded version of the 1979 exhibition, with never-before-translated first-person narratives by the artist about her end of the deal. Always ahead of her time, Calle presaged our current lives under ubiquitous technological surveillance while testing and teasing the ever-thin line between intimacy and estrangement. —Hakim Bishara

Buy on Bookshop | Siglio Press, November 2024

Peggy: A Novel by Rebecca Godfrey with Leslie Jamison

In my early 20s I developed a fascination with Peggy Guggenheim, the brilliant yet flawed collector and arts patron whose undeniable contributions to modern art have often been eclipsed by sexist narratives of her personal life. Addressing these apparent contradictions while doing justice to her taste-making legacy is no small feat (Francine Prose achieves this in her 2015 biography, The Shock of the Modern). That’s why I’m so eager to dive into late Canadian author Rebecca Godfrey’s Peggy: A Novel, an imagined account of Guggenheim’s lived experiences told from the perspective of the woman herself. (The novel was completed by Leslie Jamison after Godfrey’s death in 2022.) Will the genre of fiction open up new possibilities to recast her story in a different, more encompassing light? I’ll report back … —Valentina Di Liscia

Buy on Bookshop | Random House, August 2024

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie

The title may suggest a technical manual, but The Use of Photography, published in French in 2005 and recently translated to English, is anything but dry. The moving memoir follows an intense affair between the authors that began during Ernaux’s treatment for breast cancer at the Institut Curie in Paris. Struck by the sight of clothing strewn around rooms and dinners left out overnight, the authors began photographing these compositions. The photographs both structure the narrative and serve as vehicles for meditations on pleasure, pain, melancholy, and the transience of life. The “use of photography” here is much like the use of all art: to remember, to comfort, and to record and perhaps free ourselves from the past. —Natalie Haddad

Buy on Bookshop | Seven Stories Press, October 2024

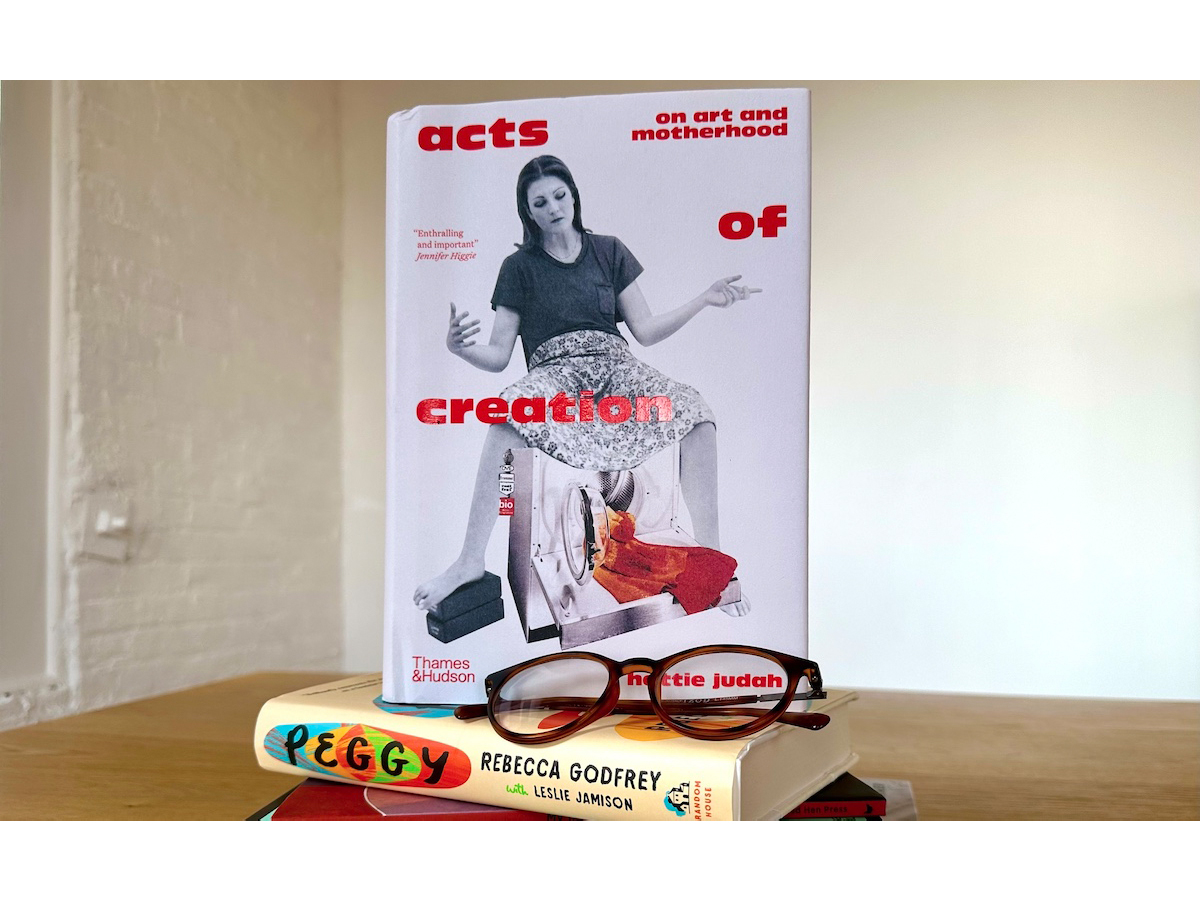

Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood by Hettie Judah

Critic Hettie Judah introduces her new book with a stern, ghostly figure she dubs “the monstrous child,” hands coated in red and blue paint. Unlike Madonna and Childs and pastoral scenes of families frolicking that pepper Western art history survey courses, Marlene Dumas’s “The Painter” (1994) sharply departs into a path rooted in personal experiences of mothering and art-making. Judah explains that this is her aim in Acts of Creation: to decipher how art across the centuries has fashioned the mother “as a medical subject, a spiritual ideal and social construct.” Her last book, How Not Exclude Artist Mothers (and Other Parents) (2023), presented a concise study of the needs and desires of artist-parents working today, an important jumping-off point I plan to re-read before diving into Acts of Creation. Weaving rigorous research with around 150 images, Judah brings her characteristic precision to a subject that has only recently been given its due. I’m counting on this book to restructure my understanding of how art created mothers from imagined, impossible ideals, and how mothers create art from their own realities. —LA

Buy on Bookshop | Thames & Hudson, September 2024

The Unseen Truth: When Race Changed Sight in America by Sarah Lewis

Colloquially, we tend to trade in the term “caucasian” for “white,” pat ourselves on the back, and leave it at that. Enter scholar Sarah Lewis and her brilliant intervention, which pries open the fissures running across popular understandings of race and sight. She focuses on the untold story of the images that circulated in the US during Europe’s Caucasus War, which concluded just before the end of the American Civil War. These renderings of communities in parts of present-day Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia forced the American public to confront the dissonance between the term “Caucasian” and actual people in the Caucasus region, posing a direct challenge to whiteness. Through reproductions of paintings, photographs, posters, and maps, Lewis brings a woefully understudied time period to light. It’s a pivotal chapter in the story of racism, yet often treated like a footnote. Lewis’s book more than rectifies this, offering a necessary reorientation for ethnic studies scholars, art historians, and everyday readers alike can learn from.

Buy on Bookshop | Harvard University Press, September 2024

My Infinity by Didi Jackson

If Hilma af Klint’s monumental paintings could speak, what would they say? Didi Jackson answers this with a resonant collection of poems, several written from the perspective of the Swedish mystic artist or taking her pioneering abstract works as entry points. Jackson, who’s published one book of poetry already, masterfully spins af Klint’s spirit into her lyrical, deeply personal writings. A pair of swallows in af Klint’s “The Tree of Knowledge, No. 2, Series W” (1913) figure into one poem quietly reflecting on her husband’s suicide, time she spent in Greece the following summer, and grief’s tendency to split our sense of self right down the middle. It’s no surprise that visual artists often write poetry, but a poet inspired by a visual artist can cast a unique kind of spell, one My Infinity promises to deliver. —LA

Buy on Bookshop | Red Hen Press, September 2024

Our Lady of the World’s Fair: Bringing Michelangelo’s “Pietà” to Queens in 1964 by Ruth D. Nelson

I’ve called Queens home for two decades, and yet I’m still constantly bumping into some new oddity about the New York World’s Fair, which, for better or for worse, may be the thing for which we’re best known. The 1964 edition was like an Olympics for culture, akin to the Venice Biennale in scale and a pop-up in commercialism, stranger than them both. Hosted at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, the event boasted 139 pavilions by 80 nations, with exhibitions, rides, food; it brought Belgian waffles and the Ford Mustang into American popular consciousness.

It also marked the first — and only — time Michelangelo’s “Pietà” (1498–99) left its longtime home at St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. In Our Lady of the World’s Fair, author Ruth D. Nelson explains that the marble masterpiece made the Vatican’s pavilion the second-most visited one of the event, “after General Motors.” Nelson’s got a winkingly wry sense of humor, but she’s first and foremost a scholar. The book is well-researched, grounded in historical context, and neatly subdivided into chapters and sections. But a subtle warmth lights this book from within: The author visited the fair as a child. “Though I do not remember much,” she writes, “what remains in my heart is a sense of wonder and happiness.” It introduced her to the “Pietà,” possibly sparking her interest in art history; she’s come full circle with this book. —Lisa Yin Zhang

Buy on Bookshop | Three Hills, an imprint of Cornell University Press, September 2024

Occult: Decoding the Visual Culture of Mysticism, Magic and Divination by Peter Forshaw

“As above, so below,” a phrase attributed to the Ancient Egyptian sage Hermes Trismegistus, opens this new and deeply insightful book by researcher Peter Forshaw. It takes us on a journey through the visual language of occult traditions broadly ranging from Europe and the Mediterranean to West and Central Asia. The author poetically describes the occult as “a belief in the existence of correspondences between all things, of a web of creation, a great chain of being.”

We begin with foundational elements, such as astrology and alchemy, and move into the philosophies of magic, closing out with a look at the rise of spiritualism and the New Age movement. The book is lush with images for artists and visual thinkers alike to pore over, such as a two-page spread of the 1411 Horoscope of Sultan Iskandar from the Book of the Birth of Iskandar, the grandson of Timur, the Turkmen-Mongol founder of the Timurid dynasty, and Victor Brauner’s “The Surrealist,” a 1947 self-portrait that draws heavily from tarot symbology. Forshaw shows us how these images are in visual dialogue with each other across centuries, contextualizing the world of astrology apps and tarot influencers today. —AX Mina

Buy on Bookshop | Thames & Hudson, September 2024

Sam Gilliam by Ishmael Reed, Mary Schmidt Campbell, and Andria Hickey

Sam Gilliam experimented with abstraction over six decades, up until his death in 2022 at age 88. The artist’s eponymous monograph from Phaidon gathers images of his prolific oeuvre, from his early career affiliation with the Washington Color School to his sculptural drape paintings and the textural canvases made toward the end of his life. The allure of Gilliam’s works is so dependent on their texture, tactility, and physicality, best experienced up close and personal. But the publication reproduces his artworks with great detail, offering close-up shots capturing their material quality — the staining and smudging, the drips, the crinkling — and allowing for close study, resulting in a gorgeous object of a coffee table book.

Phaidon’s smartest choice, perhaps, is the inclusion of a lengthy text by Mary Schmidt Campbell. The art historian and curator dives in with a rich essay explicating the ways that Gilliam pushed boundaries as a Black abstractionist, “standing comfortably in the contradiction between radical control and liberating improvisation.” It’s a fantastic exploration of every facet of Gilliam’s life and work — his Southern upbringing, his influences (jazz, Japanese culture, politics), and his evolution as an artist. It’s accompanied by a poem by Ishmael Reed, a transcribed commencement speech given by Gilliam to the Memphis School of Art in 1986, and a detailed timeline of his career by Andria Hickey. —Jasmine Weber

Buy on Bookshop | Phaidon, December 2024

Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice, edited by Glenn Kaino and Mika Yoshitake

I’m often dumbfounded by the fact that we humans spend time, energy, and resources on anything other than mitigating ecological collapse and ensuring justice for every living being, yet I’m immediately suspicious of anything art world-related that claims to do just that. Published in conjunction with a show opening on Saturday at the Hammer Museum as part of PST ART: Art and Science Collide, the exhibition catalog Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice features environmental art practices concerned with the climate crisis and its disasters and their intersections with social justice issues. Anticipating the book with writings by Chus Martínez — along with the exhibition itself, featuring works by intergenerational, international artists and activists including Mel Chin, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Zheng Mahler, and Otobong Nkanga — I’m hoping that it will at least change jaded attitudes like mine, and perhaps, in turn, help change the world. —Nancy Zastudil

Buy on Bookshop | Delmonico Books and the Hammer Museum, October 2024

Painted: Our Bodies, Hearts, and Village: Pueblo Perspectives on the American Southwest

In 1898, a broken wagon wheel forced two artists traveling to Mexico to stay in Taos, New Mexico. The two would go on to be founding members of the now-famed Taos Society of Artists (TSA), a group of Anglo-American painters who depicted the landscape and Native peoples of the Southwest, including Taos Pueblo, an epicenter of exchange. Trade route-associated tensions are evident in the group’s truly beautiful paintings, but Pueblo people’s stories neither begin nor end with the TSA. The exhibition Painted: Our Bodies, Hearts, and Village on view from May of 2023 through last July at the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine, critiqued how the TSA’s works have been exhibited and contextualized to date, centering Native worldviews through consultation with and curation by Pueblo and other Indigenous artists and culture bearers, including 2022–23 Center for Craft Archive Fellow Siera Hyte (Cherokee). With works from the museum’s holdings, the Lunder Collection, and select loans installed amidst Virgil Ortiz’s dynamic exhibition design, plus critical writings, I’m eagerly awaiting this catalog’s release. —NZ

Buy on Bookshop | Delmonico Books and the Colby College Museum of Art, October 2024

Beyond Vanity: The History And Power Of Hairdressing by Elizabeth L. Block

An art historian and senior editor at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Elizabeth L. Block is also a pioneer in the field of hair studies (yes, please). Her book Beyond Vanity takes on hair and hairdressing in early America as the important cultural signifiers that they are, examining, in her words, “the concept of hair as a site of critical meaning in society.” This is my favorite kind of history, about overlooked art and artists — hair and hairdressing have been mostly ignored or scorned as frivolous (read: feminine) — that also has high stakes. Yes, it’s a fascinating look at some fashionable and fabulous material culture, and is beautifully illustrated, but it’s also a clear reminder of how much the culture around hair reflects the racial and economic inequalities of society writ large. I live in California, where the passage of the CROWN Act (“Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair”) in 2019 is a reminder of how discrimination and control are a still-living part of America’s complicated relationship with hair. —Bridget Quinn

Buy on Bookshop | MIT Press, September 2024

The State Of Fire: Why California Burns by Obi Kaufmann

Obi Kaufmann is an artist and naturalist whose bestselling California Field Atlas (2017) is a beloved illustrated guide to the flora and fauna of the state. He’s published several illustrated books of California natural history, on forests, coasts and deserts, including The State of Water: Understanding California’s Most Precious Natural Resource (2019). His newest book, The State of Fire, feels inevitable and welcome. I had to leave San Francisco in 2020 due to the pandemic and its complications, and now live in a small town surrounded by the impending possibility and sometimes terrifying fact of wildfire. Like a lot of Californians, fire has become a fairly obsessive interest. Add Kaufmann’s inimitable watercolor illustrations and I can’t wait to get my hands on this manual of the natural world and California history. Pair with writer Manjula Martin’s 2024 memoir, The Last Fire Season, for a visceral-plus-visual understanding of what it is to love the natural world and to live alongside fire, itself an essential part of that world. —BQ

Buy on Bookshop | Heyday Books, September 2024

R.H. Quaytman: Book

Book, as the artist writes in her introduction, is the second volume in a project that began with Spine, her retrospective volume from 2011 that covers every painting from the first 20 chapters of the ongoing book of her oeuvre. And it is the first volume to undisguisedly arrive wearing its name the way a person does, with its first designating letter boldly capitalized. Like a physiognomic map of its dimensions, every individual painting — each one made on a square or rectangular plywood panel with beveled edges resembling the pages of an uncracked book, their dimensions related to those of a sculptural work from 1928 by the Russian-born Polish constructivist artist Katarzyna Kobro — is reproduced to scale, existing entirely “within the context of the page.” Quaytman spent the last two years writing and composing Book, and, when it is finally published later this fall, it will be an art book more than just in name. —V. H. Wildman

Buy on Bookshop | Glenstone Museum, October 2024

Propagandopolis: A Century of Propaganda from Around the World, edited by Damon Murray and Stephen Sorrell

Just in time for election month in the US, a collection of propaganda imagery from around the world to stir the senses — and hopefully alert the mind to the uses and abuses of fear-mongering in the present through its many guises in the past. Propagandopolis, culled from a website of the same name that sells reprints (you too can own a 1960 Chinese army training poster!), is arranged alphabetically by country, with examples of visual bombast from Afghanistan and Angola to Yugoslavia and Zimbabwe. Intended to horrify, rouse sentiment, or move to action, these images are variously succinct, lush, fearsome, and occasionally inadvertently hilarious (“Normal people don’t need drugs,” claims a British health council poster from 1965 picturing such creepily clean-cut youth it must have prompted a run on the nearest street-corner dealer). In the book’s informative short history of the genre, contributing writer Robert Peckham reminds us that “much artmaking exists in an ambiguous space between propaganda and commerce.” And the reproductions remind us that beauty is sometimes next door to coercion. —Melissa Holbrook Pierson

Buy on Bookshop | Fuel, November 2024

[ad_2]