[ad_1]

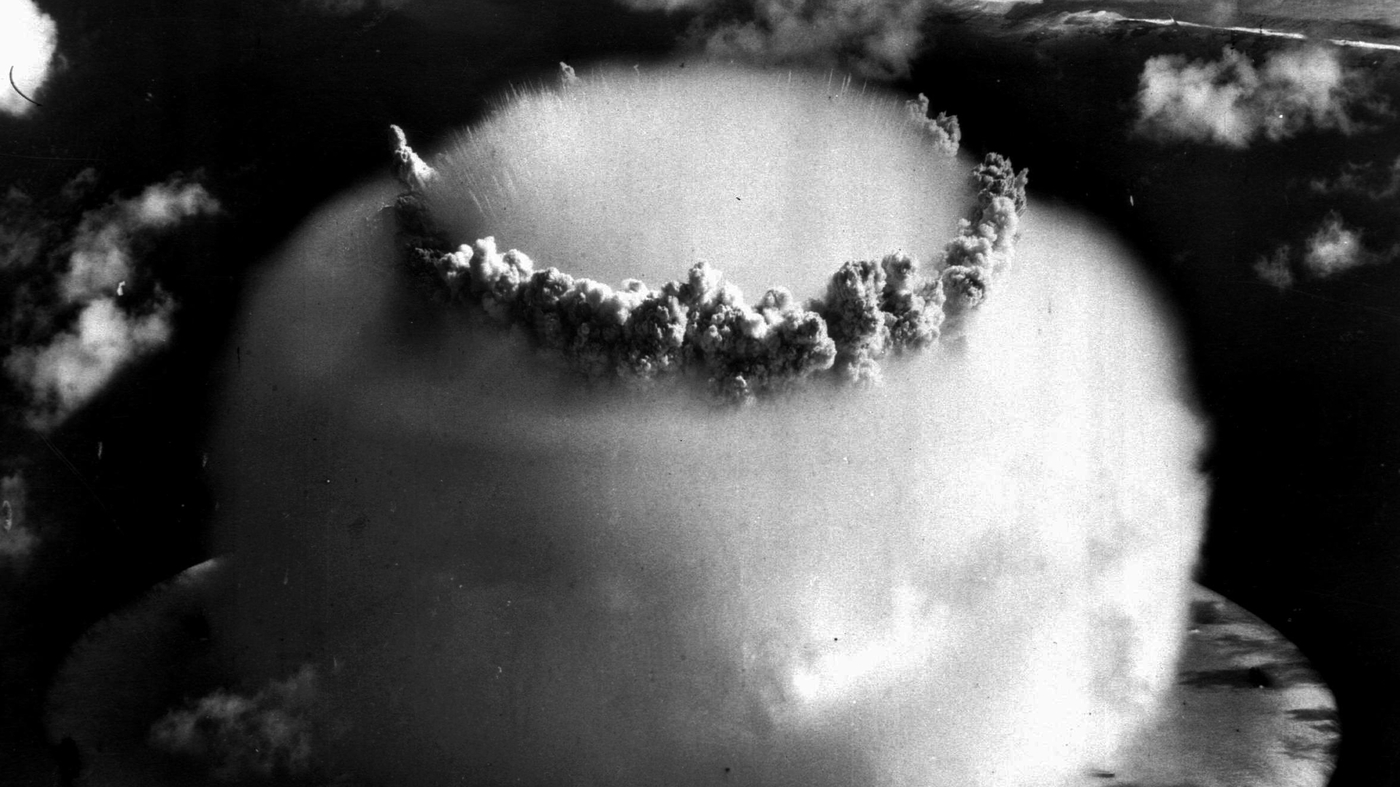

So-called atomic veterans who worked on nuclear weapons tests, like this one from July 25, 1946 file photo above Bikini atoll in the Marshall Islands, are fighting to renew funds that compensate them for health effects from their work.

File/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

File/AP

So-called atomic veterans who worked on nuclear weapons tests, like this one from July 25, 1946 file photo above Bikini atoll in the Marshall Islands, are fighting to renew funds that compensate them for health effects from their work.

File/AP

In the Spring of 1947, Navy sailor Lincoln Grahlfs went to an Oakland, Calif., hospital suffering from a 103-degree fever, a strange facial abscess and an abnormal white blood cell count.

A doctor there responded with an unorthodox treatment: x-rays to the sailor’s face with only a shield to cover his eyes.

Soon after, the abscess and other symptoms cleared.

“He said ‘we call that the hair of the dog that bit ya,'” Grahlfs told NPR.

The dog that bit Grahlfs, in this case, was his exposure to the U.S. nuclear testing program.

In his 20’s, the petty officer first class participated in Operation Crossroads in the Pacific Ocean, the first atomic bomb tests since the 1945 nuclear weapon attacks in Japan.

Over the next seven decades, more mysterious illnesses surfaced for Grahlfs–and in the generations of his family that followed.

Military servicemembers like Grahfls are known as “atomic veterans,” and they’re on the verge of losing federal benefits meant to compensate for the long-term health effects of their work.

They’re part of a group fighting for a critical lifeline known as the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, or RECA. The 34-year-old law is set to expire next month.

“I am affected by this thing as far as I’m concerned — lifetime — because it’s in my blood,” Grahfls said from his senior living facility in Madison, Wisc.

At 101 years old, he is the country’s oldest known atomic veteran.

He’s one of least 200,000 U.S. troops who participated in the tests and cleanup operations during World War II and later in the Pacific Ocean, the Nevada desert, New Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean.

They took the human brunt of deadly ionizing radiation that contaminated nearby lands, water and communities. Many are said to have died of related illnesses.

Now, a group of lawmakers are pushing for to renew legislation to recognize that a new generation of workers and residents may still be affected by the tests, including uranium mine workers and so-called “downwinders” caught in toxic exposures.

“A godsend”

Keith Kiefer, national commander of the National Association of Atomic Veterans, or NAAV, participated in cleanup operations in the 1970s.

The Air Force veteran’s work was based at the Enewetak Atoll in the Marshall Islands, and he’s suffered his own share of illnesses. He isn’t eligible for the existing version of RECA , but a new Senate bill would expand the program to include him.

Kiefer took over as head of the organization in 2018 and says he has seen the toll of radiation exposure on the group’s members and their families.

“In some cases, you can’t hold a job at all… But on top of the suffering… you have the financial burden,” Kiefer said. “Often RECA is a difference for these veterans between potentially becoming bankrupt or becoming homeless. So it’s you know, it’s a godsend.”

Since its enactment in 1990, RECA has provided lump sum payments of up to $75,000 to atomic veterans and others sickened by the nuclear testing program. In all, the Justice Department program has disbursed $2.7 billion in payments to more 40,000 recipients.

The Oscar-winning film of the year, Oppenheimer, spotlighted the Manhattan project and the atomic bomb’s earliest days. But a key group of lawmakers say the film’s attention may not be enough.

“Your government poisoned you”

On Capitol Hill, Missouri Republican Sen. Josh Hawley has spotlighted the issue in his state, where generations of Missourians have been exposed to radioactive waste tied to the Manhattan project.

And now he has a dire warning for Congress.

“We have one month until the RECA program expires, goes dark,” he says on his way to Senate votes on a recent morning.

In the past year, the Democratic-led Senate has approved multiple bipartisan bills to reauthorize and expand the RECA program, with a more recent amendment garnering a large bipartisan vote. And Hawley has threatened to hold up additional legislation to pass the plan in the Senate again.

However, the Republican-led House has refused to take up RECA for months. Hawley is betting House Speaker Mike Johnson will change that.

“It’s going to be really hard to …say, ‘No, we think that you should get nothing despite the fact your government poisoned you,” Hawley said. “I think at the end of the day, the speaker is not going to want to deliver that message right before an election.”

Some House Republicans have raised alarm about the plan’s price tag.

However, sponsors say they’ve addressed those concerns. They say a 2023 estimate projecting the program’s costs of $143 billion has since been shaved down to $50 billion to $60 billion instead.

“Thousands of Americans will lose the lifesaving, literally lifesaving help that they have come to depend on,” Hawley said. “And people in my state, victims in my state, in New Mexico, other states will get nothing.”

“An American issue”

New Mexico Democratic Senator Ben Ray Luján knows about the need for that lifesaving help all too well.

He’s seen the scores of New Mexicans and tribal members sickened since Trinity, the code name for the first nuclear test in 1945.

His father also worked at the Los Alamos Nuclear Laboratory, where the weapon was developed. His father died in his 70s after he was diagnosed with Stage IV lung cancer.

“He was not a smoker, but he got sick. And we believe he got sick because of the work that he did,” he said. “I saw him leave sooner than he should have. And what that did to my mom and him and to our family.”

This past week, Luján and Hawley were among a group of 30 bipartisan lawmakers who signed a bipartisan letter to Speaker Johnson demanding the House take up the legislation before time runs out.

Every year since 2008, Luján has filed legislation to expand the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act. This annual 17-year tradition is now consumed by supreme frustration.

“We need to pass this. This injustice is far too long. It’s decades and decades old,” Luján said. “This is not a blue state or red state issue. This is an American issue.”

Grahlfs says regardless of the program’s fate, the struggles remain.

A retired sociology professor who wrote about the atomic vets, Grahfls has outlived both his children who also suffered from curious illnesses. A granddaughter was born with a deformity.

He argues it’s all tied to his exposure to radiation.

“People who have been affected by radiation are still affected,” he said, “whether they sunset the the act or not.”

Next week, the atomic veterans will join forces with other survivors on Capitol Hill to personally pressure Congress to approve the plan that acknowledges their sacrifices.

[ad_2]