[ad_1]

Heather Booth has a secret, of sorts. It was unknown to me, at least, and to a lot of the activists who’ve worked with the veteran organizer in recent years.

In 1968, in the first presidential election in which she could cast a ballot, she did not vote for the Democratic nominee, Vice President Hubert Humphrey. A passionate grassroots anti-war and civil rights activist, Booth believed that he hewed too closely to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s policy of escalation in Vietnam. She wasn’t alone; many people on the left refused to back Humphrey. Some sat on the sidelines; others, like Booth, voted for Dick Gregory, the Black comedian and activist who ran a gadfly but politically attuned campaign that year. Richard Nixon beat Humphrey by 0.7 percent of the vote.

“I was so angry about the war, I couldn’t vote for Humphrey,” Booth says as she sits in her small home office in Washington, DC, the walls decorated with posters reflecting the causes and campaigns to which she has devoted her life. While Booth believes that her vote for Gregory didn’t tip the balance (“I looked it up—he got about 50,000 votes,” she says), the general disenchantment of the left arguably did.

Then came the consequences. “Because of the social fracture,” Booth recounts, “Nixon was elected. He pursued the war for another four years; hundreds of thousands, if not millions more, died in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam.” Then there was Watergate; and Nixon’s elevation of political henchmen like Roger Stone, Pat Buchanan, Donald Rumsfeld, and Dick Cheney; and the GOP’s harnessing of the white ethnic grievance politics that ultimately gave us Donald Trump.

Some 56 years later, Booth is still haunted by this story, which has become a kind of touchstone for her—a reminder of what’s at stake in the 2024 election. “She’s seen this before,” one old friend of Booth’s tells me on background: Johnson, a Democratic president with a remarkable record of domestic policy accomplishments, brought down over an unpopular war, and his even more liberal vice president rejected as his successor for the same reason. It’s one of the reasons that, at age 78, Booth agreed to take on the role of spearheading progressive outreach for President Joe Biden’s reelection campaign, reprising a job she did in 2020, when she ran his senior citizen and progressive outreach. But she didn’t know how hard it would be this time around. As in 1968, a ruinous war threatens to split the Democratic coalition. And now Booth is in the position of trying to knit those two sides together.

The founder of the legendary Midwest Academy in Chicago, which has trained progressive organizers for half a century, and a veteran of almost every major American left/liberal movement for even longer, Booth was the first person hired to lead progressive outreach for Biden’s 2020 run. This time around, his campaign brought her on not in mid-summer, as it did in the previous election, but in January. Biden needs her. He is facing resistance from the left wing of his party and from moderate Muslim and Arab American Democrats, all of whom are furious about his support for Israel’s bloody assault on Gaza in the wake of the October 7 Hamas attack. Hamas killed at least 1,200 Israelis and took more than 200 hostage; Israel, with US-supplied weapons, has killed at least 35,000 Palestinians and is starving the population. In response, a coalition of progressives, Muslims, and Arab Americans has launched a campaign in several states calling on Democrats to vote “uncommitted” or to leave their ballots blank in the primaries, signaling their protest of Biden’s stance on the war. “The movement is frayed over Gaza,” says Maurice Mitchell, the national director of the Working Families Party, who has known Booth for more than 20 years and whose organization is helping to spread the uncommitted campaign.

“There’s nobody else I can think of who could play this role,” says Alex Han, a longtime Chicago labor and progressive organizer who has worked alongside Booth, adding that he has a “deep appreciation” for her personally and her work. Now the executive director of In These Times (full disclosure: I worked there in the mid-1980s), Han has long been involved in progressive politics and was Senator Bernie Sanders’s Midwest political director in his 2020 campaign. “Heather’s storied history and ironclad reputation as a change-maker for justice make it possible that we wind up with a united front against fascism in November,” he says. Possible, that is, but not inevitable.

Sometimes it feels as if Biden’s progressive outreach director is trying to reach the Heather Booth of 55 years ago. Can that be done—with a president implicated in a devastating war, seemingly ignoring huge swaths of his base, and up against a second coming of the democracy-immolating, race-baiting, serial sexual assaulter Donald Trump? We’ll find out.

“She knows the left needs liberals, and liberals need the left,” says Michael Kazin, the Georgetown University historian and scholar of social movements, who has been friends with Booth for over three decades. He isn’t sure whether she can bring the left on board with Biden’s presidential campaign. But he believes that if anyone can do it, Heather Booth can.

The 2016 documentary Heather Booth: Changing the World called its subject “the most influential person you never heard of.” For her boosters, the reason Booth might be able to pull off her current assignment is that for more than half a century, wherever the big progressive fight was, she was there. She worked on Mississippi’s 1964 Freedom Summer with Fannie Lou Hamer, as part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; was involved in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in 1965; and began organizing the abortion collective known as the Janes that same year. “She was the original Jane, literally!” says her friend Robert Creamer, a progressive strategist and organizer who has known her since the late ’60s. Booth gave out her phone number and fielded calls from women seeking abortions.

An organizing spirit has pervaded her life. Dick Flacks, a former SDS colleague of Booth’s, is an emeritus professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and a beloved elder statesman of the movement. Eight years older than Booth, he was her professor at the University of Chicago. “So she comes up to me one day and says, ‘Professor Flacks, I just want to tell you how intimidating you are. It discourages students to speak,’” he says, chuckling at the memory. “How intimidating could I really have been if she could come up to me?” Nevertheless, he recalls, “she changed my whole style of teaching in one encounter. She ‘organized’ me right there!”

With the money she won after suing an employer for wrongful termination after she encouraged its secretaries to form a union, Booth started Midwest Academy in 1972. Then she cofounded Citizen Action, which at its height had affiliates in at least 34 states, and the Citizen/Labor Energy Coalition, both of which worked on local and state environmental and energy issues. CLEC, Creamer notes, was also Booth’s way of trying to “heal the breach” between unions and the New Left that widened painfully after the election of 1968. CLEC and Citizen Action affiliates focused on local issues, not electoral politics, “be it toxic waste in Missouri, utility rates in Ohio or tax reform in Connecticut,” as The New York Times Magazine noted in an admiring 1983 profile of their grassroots uprising.

It was Ronald Reagan’s victory in the 1980 presidential election that spurred Booth’s personal and organizational turn to electoral politics. “If you don’t do politics, politics does you,” a friend told her. That same year, Booth herself said, “If we want a majority constituency, we need alliances with people who have organized primarily in an electoral direction. We need to build a political machine.”

And so she did. In Sam Rosenfeld’s 2017 book The Polarizers, Booth is credited with infusing the large-scale renewal of door-to-door canvassing, a hallmark of the civil rights movement, into Democratic politics. Mitchell calls her the “OG organizer.” In that role, she helped elect Chicago’s first Black mayor, Harold Washington, in 1983 and again in 1987; supported Jesse Jackson’s landmark presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988; and helped elect the country’s first Black female senator, Illinois’s Carol Moseley Braun, in 1992.

Ad Policy

After that, she joined the Democratic National Committee’s outreach effort to women, labor, and other progressives, and became its training director in 1996. In 2000, she became founding director of the NAACP National Voter Fund. She also worked on major policy issues and legislative efforts: She helped block George W. Bush’s Social Security privatization in 2005, headed up labor support for the Affordable Care Act in 2009, worked with Senator Elizabeth Warren to establish the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) around the same time, and got arrested supporting the rights of Dreamers to legal status in 2018.

As Warren recalled in the documentary, when she was working to establish the CFPB—which has provided $19 billion in consumer relief since its 2011 founding—she was told she needed to organize beyond the Beltway. She asked a colleague how, and that person said, “I’ve got two words for you: Heather Booth.”

The Biden campaign is betting that the same two words will stand between him and Trump.

Heather Booth is a passionate evangelist of the view that Joe Biden is the most progressive president of the last 50 years. She ticks off Biden’s achievements to me: “Whether it’s student loans [or] taking on the issue of tax fairness, Biden is fighting for so much of what progressives have always been fighting for: a more inclusive society, greater freedom, freedom to vote, reproductive freedom, climate investment, healthcare, building our infrastructure, and more.”

When I ask Booth about Biden’s record on Israel and Gaza, she’s patient with my questions. “I know the president understands people’s horror at what’s going on in Gaza and Israel. Our hearts are breaking seeing homes destroyed, people without medicine, whole families dead,” she tells me. But she makes it clear that she doesn’t think Biden’s record can or should be judged solely by that. Yet she still wants to work with those who disagree. “We care about every possible voter, including people who voted ‘uncommitted,’” she says. “One of the reasons I think I was brought on is to make sure there is outreach and engagement and understanding and listening.”

Booth and Creamer hold twice-weekly Zoom and phone meetings with members of 60 to 80 progressive groups. I was invited to listen in on one, entirely on background. All I can report is that it was impressive in its scope and diversity—and that Booth did way more listening than talking.

In 2020, hired by the Biden campaign just four months before the election, Booth had no official staff, but she recruited 250 full-time volunteers and 8,000 general volunteers. This year, the campaign will deploy additional staff for progressive outreach; officials declined to say how many, only that the effort will be more “robust.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

But then and now, Booth mainly works through progressive and progressive-adjacent groups, giving them what they say they need to be successful, whether that’s specific messaging on the administration’s stances on their issues, a surrogate to speak at their events, or connections with other organizers who are trying to do similar things. MoveOn, for instance, has more than 1,000 volunteers who say they’ll lead house parties during the campaign. “These are the vote mobilizers,” says its executive director, Rahna Epting.

Booth’s progressive outreach seeks to mobilize the members of groups like MoveOn, Swing Left, the Sierra Club, Indivisible, the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, SEIU, and others. Given that she has worked on issues ranging from abortion to financial reform to labor rights to immigration reform, Booth has ties with the leaders of almost every progressive group. She also works closely with official campaign organizations like Women for Biden, Students for Biden, and Latinos con Biden, though she points out that those groups include Democrats of every stripe, not just progressives.

Right now the campaign, and especially Booth’s effort, is widely deploying the Reach smartphone app, which was developed by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s campaign and relies on “relational organizing”: getting people who back Biden to contact their friends and family to see whether they’re open to voting for Democrats, and then sharing information about the administration’s record that’s relevant to them and ultimately getting them out to vote. It’s been piloted this year in Wisconsin, and WisDems leader Ben Wikler calls it a success. “More than half of the voters that volunteers are contacting through Reach are people that are not already on our voter list,” he told NPR in March.

In 2020, Covid made texting and phone-calling the campaign’s, and Booth’s, main approach. This year, there will be many more in-person events: house parties, and progressive surrogates like Representative Jamie Raskin, as well as Booth herself, traveling around the country to appear at meetings and rallies, even knocking on doors. The Biden-Harris campaign’s director of youth outreach, Eve Levenson, began as a volunteer for Booth in 2020. She says she’s excited to do “in-person work” this time around, and Booth’s long experience with canvassing and door-knocking over the years—remember, she helped reintroduce it to the party—“helps us understand what works.”

Melissa Byrne, a student debt-relief activist who supported Sanders in the 2016 and 2020 primaries, says Booth helped immeasurably in “amplifying” that issue in the 2020 campaign and has also evangelized on what the Biden administration has achieved on it since then. Even after the Supreme Court struck down Biden’s student-loan forgiveness plan, “they had a Plan B ready to go,” she says, and did as much as possible incrementally. One after another, Biden’s moves on loan forgiveness have added up to $153 billion for nearly 4.3 million people. Still, Byrne notes, many people, even borrowers, don’t know how much Biden has done. She and Booth are trying to change that.

Getting progressives excited about Biden was supposed to be Booth’s role, and that role would have been hard enough a year ago. But now it’s exponentially harder.

Even her admirers aren’t sure Booth can heal the fractures on the left that have resulted from the brutality of Israel’s war on Gaza. Booth “can only cook with what she has in the kitchen,” Maurice Mitchell says. “She has Biden’s domestic record: It’s hard to argue that this isn’t the most progressive administration in a long time.” But, Mitchell adds, what she doesn’t have “in the kitchen” so far are significant concrete steps on Biden’s part to stop the war in Gaza or at least minimize its horrific effects on Palestinian citizens.

Booth and I first spoke for this article on February 28, the day after 100,000 Democrats, or 13 percent, voted “uncommitted” in the Michigan primary. Since then, the uncommitted protest movement has spread to other primaries: In Minnesota, almost 20 percent of Democrats voted “uncommitted” in that state. In the New York, Wisconsin, Rhode Island, and Connecticut primaries on April 2, the protest vote made up between 8 and 15 percent of the total, with a solid 15 percent in the blue state of New York (and 25 percent in the progressive borough of Brooklyn). Meanwhile, a student protest movement has gripped college campuses; more than 2,900 protesters have been arrested or detained at 67 campus protests.

How do you find people who are upset about this issue, I ask her, but are willing to work with you on the campaign?

“Well, I’m one of those people,” she replies. “You’re one of those people.

“We care—a lot—about Gaza and Israel. We care about the health and strength of the progressive movement. I’m finding that there are people out there who’ve been waiting to engage. ‘Is someone gonna bring me some hope?’ They want hope.” To me, and to all of her political allies, Booth emphasizes the evolution in the Biden administration’s rhetoric on the issue, and particularly the evolution in rhetoric from Vice President Kamala Harris. In a March speech commemorating the 59th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Harris described the starvation, violence, and lack of medical aid that was leading to a “humanitarian catastrophe” in Gaza and called for an immediate temporary cease-fire.

Others note that Biden deserves credit for delaying Netanyahu’s planned assault on Rafah, Gaza’s densely populated southern city. Biden made his first public move against Israel’s conduct in the war in early May, halting a shipment of 3,500 bombs to Israel. But for many in the uncommitted movement, it’s not enough. Abbas Alawieh, one of the leaders of the uncommitted campaign, described that move to The New York Times as “extremely overdue and horribly insufficient.” He says that “significant” change means Biden “com[ing] out against this war. Period.”

“Heather stresses the [administration’s] evolution in rhetoric to be tougher on Netanyahu, but when the rhetoric and the action are dissonant, it’s tough,” Mitchell says. “They’re not doing enough to provide aid and save lives there.” Waleed Shahid, the former communications director of Justice Democrats, another uncommitted organizer, says that the movement showed its power when Harris made her comments at the Selma anniversary just after the Michigan primary. But, he adds, “they couldn’t have called for some kind of cease-fire back in October?”

“I keep getting calls from reporters saying, ‘The Biden campaign says you’re all going to vote for him in November, so none of what you’re doing matters!’” Shahid continues. “Really? Are they asking us to come out against him?”

LaTosha Brown, a cofounder of Black Voters Matter and an ally of Booth’s who trained at Midwest Academy, says she backs Biden, but adds that the Biden campaign “really shouldn’t be denying that [uncommitted] people might not vote for Biden. You don’t want Heather’s voice to lose authenticity.”

MoveOn’s Rahna Epting says her membership is deeply concerned about Gaza. “The frustration that manifested into the uncommitted effort is more than understandable given the growing and urgent humanitarian crisis in Gaza,” she tells me. “But at the end of the day, the best opportunity for long-term peace and ending the violence in the region is for Biden to remain in the White House, and for the people to continue to push him to do the right thing. Our continued advocacy is critical, and it is being heard. We all know that if Donald Trump had the reins, he would only make an already bad situation drastically worse.”

Mitchell insists he’s not saying that the Working Families Party won’t ultimately back the president, whom it endorsed in 2020. “The uncommitted movement is designed to be productive. We’re saying, ‘If you think you can defeat Trump without energizing major parts of our base, you’re wrong,’” he explains. The WFP works to pull Democrats to the left, but it’s also known to be pragmatic. The party worked to reelect the moderately pro-Israel New Democrat Tom Suozzi in a February special election, because he was better than his ardently pro-Israel opponent.

“We agree it’s our moral obligation to defeat fascism,” Mitchell says. “But real critiques [of Biden] are coming from progressives, especially on Gaza. I feel like I can level with Heather—and I feel like I’m hearing the real deal from her. We’re going to continue to pick up the phone with her and talk.”

For many years, Booth wasn’t mainly “Heather Booth” to many on the left. She was “Heather and Paul Booth.” Or “Paul and Heather.” Her late husband, the national secretary of SDS in the mid-1960s, spent more than 40 years working at AFSCME, the government workers’ union, including as the executive assistant to the president. They were an indomitable team, and Paul, who died of leukemia in 2018, is still adored. In an aside, Booth tells me she was arrested as part of Jews for Dreamers on the day Paul died, adding, “I did get back to see him.”

And Paul is part of the reason she’s working again this year. “I was with my son on the anniversary of when Paul died. We do it every year. It was a lovely day and a lovely time, and we sang a number of songs and shared memories. And one of the songs we sang was the Phil Ochs song ‘When I’m Gone.’ It says: ‘I won’t know the right from the wrong when I’m gone. I can’t be part of the fight when I’m gone. I guess I better do it while I’m here.’

“And I started to cry when I was singing it. I realized this is the fight. In some ways, it’s the fight about everything we’ve ever fought for and cared about as a progressive movement in our whole lives, whether it’s civil rights or women’s rights, labor rights, LGBTQ rights, the right to vote.”

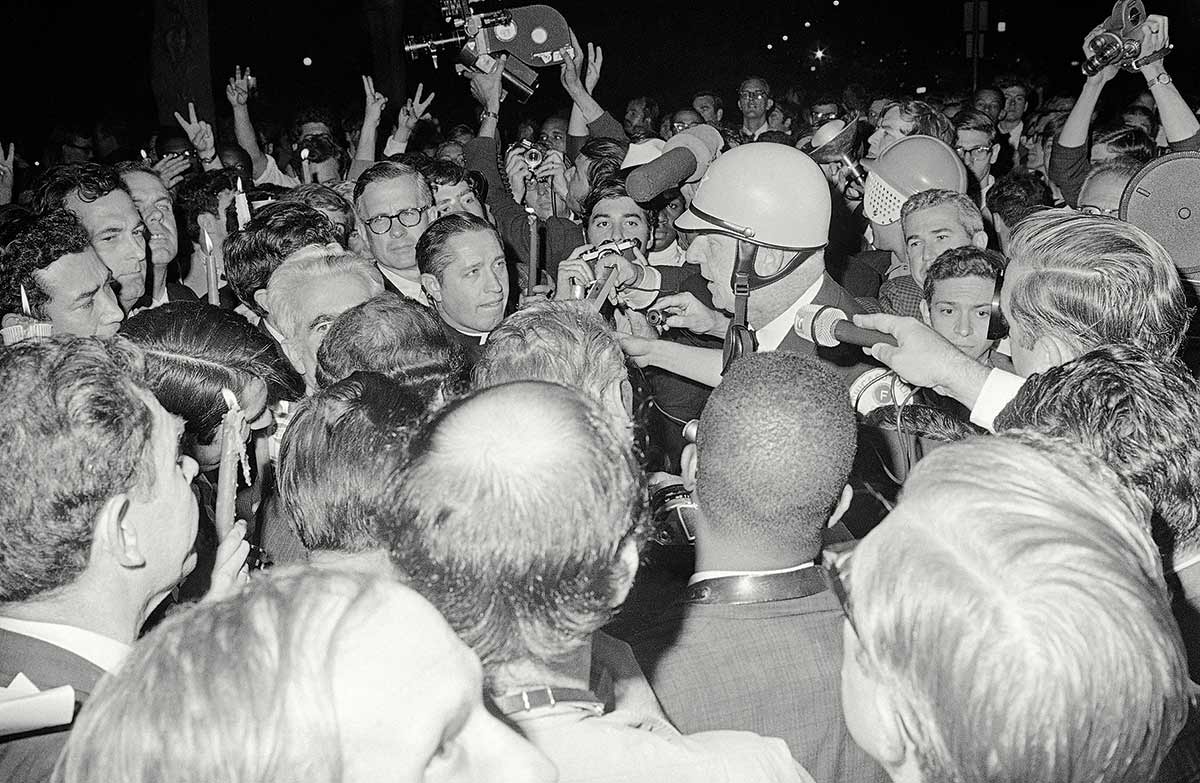

That story moved me. I was only 9 years old during the 1968 Democratic convention and the crushing election that followed. But I remember it. In case you don’t, or weren’t born yet, the convention, which was held in Chicago, was a party-destroying apocalypse. Johnson had declined to run for reelection in March, after the anti-war candidate Senator Eugene McCarthy did well in early primaries. Senator Robert F. Kennedy, the great hope of the anti-war and civil rights movements, had also jumped in, but he was assassinated in June. Inside the convention, the party’s Humphrey-supporting establishment skirmished with and ultimately shut down the insurgents who’d backed McCarthy or Kennedy; outside, anti-war protesters were bloodied by Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s brutal police force, who beat and arrested even peaceful protesters and journalists trying to report the story. It took decades for the party to heal itself, and it was activists like Heather Booth who ultimately unified it.

That legacy resonates today. “If I were Heather Booth,” Shahid says, “I’d consider myself very successful. She brought the movements—civil rights, feminism, reproductive rights, environmentalism—inside the party.” But younger activists, he adds, don’t see their causes embraced by mainstream Democrats: “They don’t see Black Lives Matter, or the movement for Palestinian rights, represented within the party right now.”

Now the Democratic Party is heading back to Chicago for its convention, and Booth and others worry that a similar fracture could put Trump back in the White House. With independent and third-party challenges from Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Cornel West, and the Green Party’s Jill Stein, there are at least three candidates who could take votes from Biden, as Stein did from Hillary Clinton in 2016. Some pro-Palestinian advocates are already planning to protest Biden’s policies at the Chicago convention in August.

Ironically, or not, many of the organizers of the uncommitted primary movement, says Alex Han, the Chicago organizer, “came through Midwest Academy or other organizations Heather founded,” including the leaders of the uncommitted effort in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. That means even if they disagree, they have a bond with her.

Booth knows this, and says she doesn’t take the bond for granted. When I note that organizers like Shahid are frustrated by Biden supporters who assume that those who voted “uncommitted” in the primaries will vote for Biden in November, she tells me quickly: “I don’t assume anything. I just try to do the work every day.”

“There are so many things we can do together,” she adds, “and facing the MAGA/Trump threat—well, the stakes are very high! We have seen that when we organize, with love at the center, even against enormous obstacles, we have made progress, even though we have so much further to go. When we organize, we will change this world.”

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply-reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish everyday at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

Joan Walsh

Joan Walsh, a national affairs correspondent for The Nation, is a coproducer of The Sit-In: Harry Belafonte Hosts The Tonight Show and the author of What’s the Matter With White People? Finding Our Way in the Next America. Her new book (with Nick Hanauer and Donald Cohen) is Corporate Bullsh*t: Exposing the Lies and Half-Truths That Protect Profit, Power and Wealth In America.

More from The Nation

We now know for sure: the movement was President Biden’s most powerful rival in the 2024 primaries. And it’s bringing that strength to the DNC in Chicago.

John Nichols

I promised my surviving family members in Gaza that I would do everything in my power to advocate on their behalf.

Laila Elhaddad

New York City police promised to minimize their presence at protests and stop brutalizing demonstrators. The NYPD is barely pretending to follow the settlement agreement.

Ella Fanger

[ad_2]