[ad_1]

Renewable energy will this year shrink fossil fuels’ reigning share of the global electricity market for the first time.

That is the key finding of Ember, a leading energy think tank based in London, which on Wednesday published its first comprehensive Global Electricity Review analysing data from 215 countries.

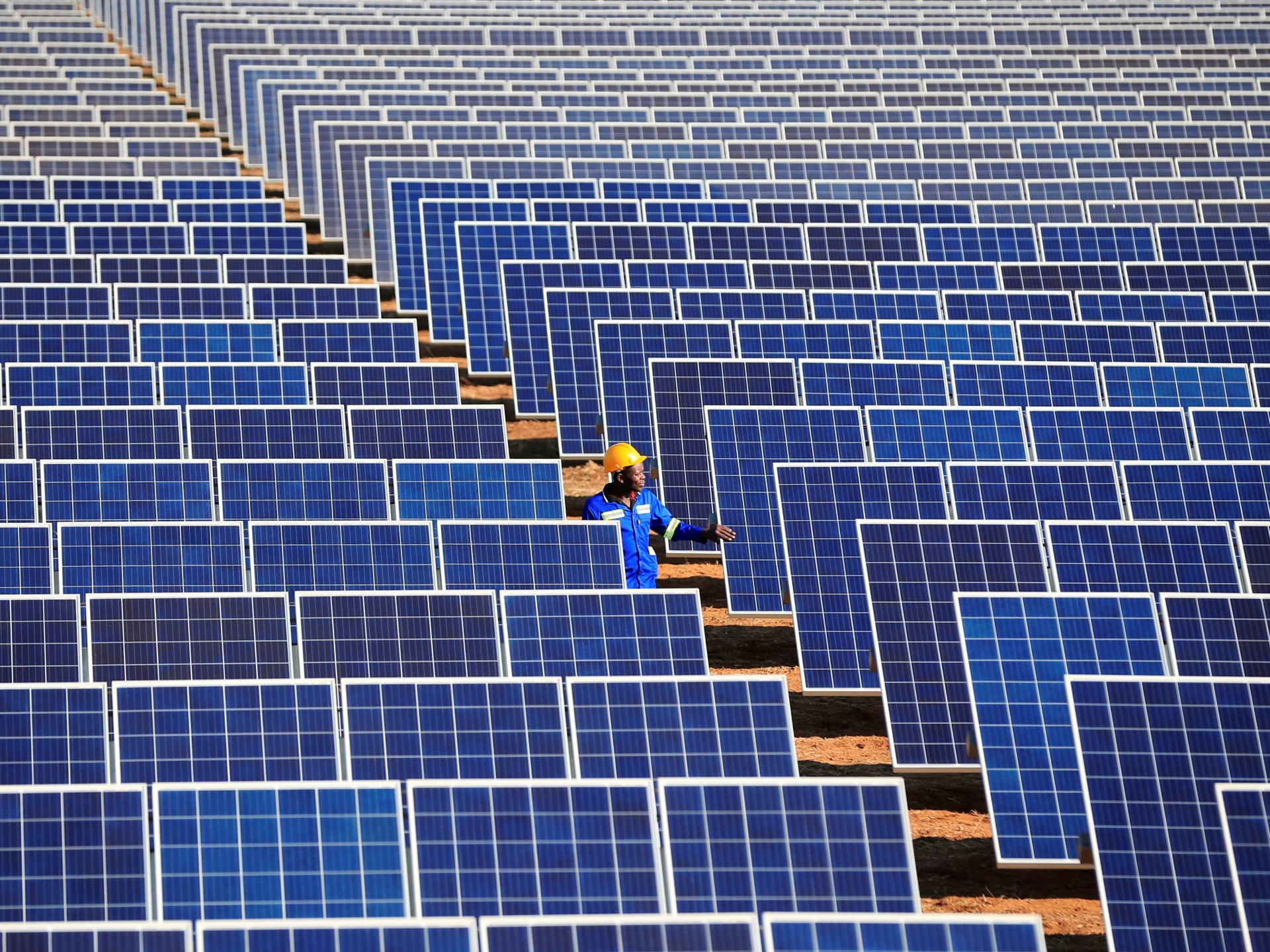

Thanks to the galloping pace of new solar and wind capacity, renewables have been claiming almost all growth in electricity demand for five years, leaving fossil fuels stagnant.

But this year, said Ember, they will also roll back fossil fuels’ market share by 2 percent – the beginning of a decade-long process of knocking them out of electricity production altogether in three dozen developed economies.

Renewables expanded by an average of 3.5 percent a year during the past decade, compared with an annual 1.5 percent in the previous decade, as prices for photovoltaic panels and wind turbines climbed down and their productivity soared.

Ember found that the world already produced a record 30 percent of its electricity from carbon-free sources last year.

Several additional factors suggest 2024 will be a turning point, said Dave Jones, one of the report’s lead authors.

For one thing, installed capacity underperformed because of light winds and droughts that hobbled hydroelectricity production – conditions that are not expected to continue.

“There’s a specific tipping point for 2023 itself,” Jones told Al Jazeera. “The buildout in solar generation only really happened towards the end of the year and it will only be in 2024 that we’ll see the full force of that buildout reflected in generation.”

In addition to the full-year effect of newly installed capacity, Jones believed a 50 percent collapse of solar panel prices in the final months of 2023 will also lead to record new installations.

Ember estimates that as a result, renewable generation this year will add a gargantuan 1,221 terawatt hours of electricity supply, compared with 513 TWh added last year.

“What’s going to happen in 2024 is going to be a next-level renewables boom, which means that for the first time, [the] fossils generation will start falling,” said Jones.

That means trouble for coal-fired power stations, but it could also mean trouble for natural gas, he said.

“There’s going to be a bit of a rude awakening on gas,” said Jones. “The gas industry before were really looking forward to coal collapsing because that was going to create a new market for them but actually … wind and solar is replacing coal and it’s replacing gas.”

Ember’s prediction relies on hydroelectric power recovering from five years of drought, and nuclear power continuing to provide just over 9 percent of the global mix.

Europe, which leads the world in clean energy production, could have progressed even faster if Germany had not decided to shut down its nuclear power plants after Japan’s Fukushima accident in 2011, said Trevelyan Wing, a fellow at Cambridge University’s Centre for Geopolitics, focusing on energy matters.

But the same forces that shut down nuclear boosted renewables, he told Al Jazeera.

“The energy transition that’s happening in Germany is to a large part because of the anti-nuclear crowd. [It] has really led the citizen-energy movement, which has installed rooftop solar panels and really made possible the near-exponential expansion of renewables in energy.”

The key role of China

China plays an outsized role on both sides of the energy transition story.

Last year it created about 29 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, twice those of the runner-up – the United States.

But it also installed half the world’s solar panels and 60 percent of the world’s wind turbines, easily rating as the green energy transition leader. It manufactures as much as 85 percent of the solar panels the rest of the world installs.

It is also a leader in the electrification of transport and heating, two of the most polluting sectors of the economy after electricity production. Last year it put more electric vehicles on the road and heat pumps into homes than the rest of the world combined, and was responsible for almost all new electricity demand.

Ember applauds this, saying, “China’s need to find new export markets is a tremendous opportunity for countries around the world to take advantage of how cost-competitive and available solar is compared to other generation sources.”

But not everyone is happy with China’s state-led model of renewables development.

“Right now the very broad spread of renewables, and especially solar, is partly based on the very large subsidies China is giving to photovoltaic infrastructure,” energy analyst Miltiadis Aslanoglou told Al Jazeera.

“Its goal is to dominate and wipe any competitors off the map so that in the coming years it will have a technology monopoly.”

The European Union and the US, leading markets for Chinese photovoltaics, are both beneficiaries and victims, Aslanoglou said.

“The accusation is that all the added value being created in China is at the expense of [what would be] a competitive market in renewables for everyone else, due to all the state subsidies being given.”

That has knock-on effects, said Aslanoglou, leaving electricity grids unprepared to carry increasing loads, and potentially up-ending the business plans of expensive gas terminals, pipelines and distribution networks, which require decades to recoup investments.

Nikos Tsafos, chief energy adviser to Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, believes that is a far preferable problem to climate change.

“What we know is that in most countries renewables are the cheapest way to produce new energy,” he told Al Jazeera. “For a country like Greece, which imports fossil fuels, renewables are cheaper and more reliable, and that creates a dynamic that is almost unstoppable.”

Under Mitsotakis, Greece has transitioned quickly, producing 57 percent of its electricity from renewables last year, and aiming to produce 80 percent by the end of the decade. For Greece, which once imported almost all of its energy, that means security of supply and price stability, undergirding what it hopes will be an economic comeback from its 2010 bankruptcy in the coming decade.

After struggling to kick-start and grow a renewable energy industry, Tsafos believes Europe has finally arrived at a very desirable problem, which is how to absorb the clean electricity it generates.

“We have hours when renewables have zero market value,” Tsafos said. “The question is no longer whether renewables are competitive, but how to reform the system to absorb them.”

Not unlike China, Europe and the US have opted for state-led solutions.

The EU’s 2020 Recovery and Resilience Fund set aside 270 billion euros ($290bn) in subsidies and loans for renewable energy installations and grid upgrades. Two years later, US President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act set aside $783bn in renewable energy and climate change mitigation measures.

“Some companies will close, others will spring up,” said Tsafos. “The energy transition is inevitable and not something you should delay or something you can prevent. If something creates a new dependence, you have to manage the tradeoffs.”

[ad_2]