[ad_1]

Ten years after the massive street protests that overthrew Ukraine’s president—and helped precipitate war with Russia—another former Soviet Republic teeters on the brink.

Georgia is a small, mountainous country that neighbors both Russia and Ukraine. Beginning on April 15, demonstrations by tens of thousands of mostly young people have brought its capital, the ancient city of Tbilisi, to a standstill. The self-styled pro-Western protesters decry the government’s perceived turn away from closer integration with the European Union, which is supported by over 80 percent of Georgians.

The catalyst for the current unrest was a proposed law requiring nongovernmental organizations and civil society groups that receive at least 20 percent of their funding from abroad to register as “organizations carrying out the interests of a foreign power.” It was dubbed the “Russian Law” by the opposition, after similar legislation passed by Vladimir Putin in 2012. Domestic critics, as well as the governments of the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and other Western countries, accuse the governing Georgian Dream party of backsliding on its commitment to EU accession. They invoke the supposed Moscow sympathies of the party’s founder, the reclusive billionaire businessman Bidzina Ivanishvili, who made his fortune in Russia in the 1990s.

“The EU has clearly and repeatedly stated that the spirit and content of the law are not in line with EU core norms and values,” the EU’s High Representative Josep Borrell said in a statement. “The adoption of this law negatively impacts Georgia’s progress on the EU path.”

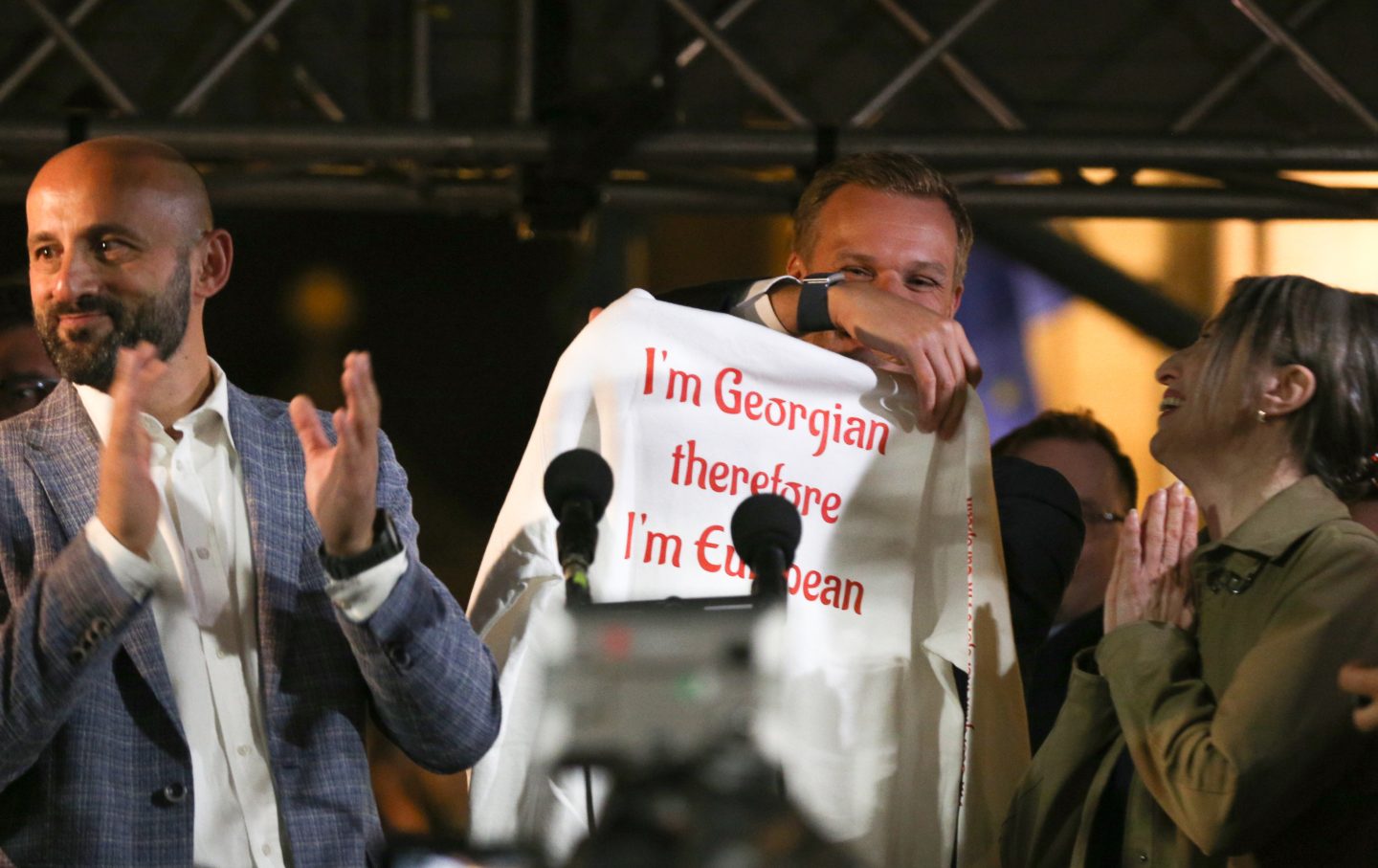

Yet despite the pressure, on May 14 Georgia’s parliament passed the law with 84 votes in favour and 30 against. Since then, the crowds have only swelled, with protests spreading across the country amid increasingly vocal demands for the government to resign. The foreign ministers of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Iceland, as well as the head of the German parliament’s foreign relations committee, joined the crowds in Tbilisi on Wednesday. It is highly unusual for senior foreign politicians to attend anti-government protests in third countries. Indeed, when Italy’s then–deputy prime minister Luigi Di Maio met with French “yellow vest” protesters in 2019, his visit was condemned by France’s foreign ministry as an unacceptable provocation.

On Saturday, Georgia’s president Salome Zourabichvili, a Parisian-born former French diplomat and erstwhile Georgian Dream ally turned opposition supporter, vetoed the law. However, Georgian Dream has the parliamentary majority required to override it.

Over the past week, senior protest figures have invoked Ukraine’s “Euromaidan” protests from 2014 and begun to call for the government’s ouster. “Believe me, there will be a color revolution in Georgia,” declared the opposition MP Tako Charkviani immediately after the law passed in parliament. Her comment referenced the 2003 overthrow of then–Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze that became known as the Rose Revolution and the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine that initially ousted Viktor Yanukovich during his first term in power. Since then, “color revolution” has become a byword for pro-Western, protest-driven regime change.

The Western media has, by and large, uncritically echoed the protesters’ narrative. According to their accounts, the standoff pits young idealists defending democracy against an authoritarian regime controlled by a pro-Putin oligarch determined to crack down on civil society and drag Georgia away from its European destiny into Russia’s arms. Ominously, such rhetoric is being used to justify calls for the ouster of a democratically elected government mere months before the October parliamentary elections, which, polls show, the opposition is expected to lose by a large margin. The reality, however, is much less black-and-white.

Current Issue

One of the biggest differences between what is happening now in Georgia and the events in Ukraine in 2014 is that then-President Yanukovich had formally rescinded Ukraine’s association agreement with the EU in favor of a last-minute deal with Russia. By contrast, despite its being routinely described as anti-European, it was the Georgian Dream–led government that pushed for, and ultimately secured, Georgia’s coveted EU candidate status just six months ago, having brought forward the application by two years—hardly the behaviour of a government merely paying lip service to EU accession. Apart from some tough rhetoric, the only concrete evidence of the government’s alleged anti-European turn cited by protesters concerns its resistance to joining EU and US sanctions on Russia. Yet the government has argued that doing so would not appreciably hurt Moscow but may open Georgia up to economic and even military reprisals. The stakes are high: Georgia’s revenues from Russia, its second-largest trading partner, represented more than 10 percent of the country’s GDP in 2023; what’s more, thousands of Russian troops remain stationed in the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and North Ossetia since the Russia-Georgian war of 2008.

Given these realities, acknowledging the serious costs of antagonizing the Kremlin is not the same as appeasing it. Many Georgians appear to agree, according to a 2022 poll conducted by the International Republican Institute and partly funded by USAID. Nearly half of respondents were in favor of either a pro-Western foreign policy that also keeps up good relations with Russia (38 percent) or an outright pro-Russia policy (9 percent), together outnumbering the 43 percent who wanted Georgia’s foreign policy to be exclusively pro-Western.

Nor is it accurate to describe the Georgian government as authoritarian. Though Georgian politics is rife with corruption, intimidation, and institutional capture, it also boasts a proliferation of political parties, a combative and free press and numerous independent NGOs and grassroots activist groups. Many if not most of these actors are vocal critics of the government—as are some of Georgia’s largest media companies. Nevertheless, since first coming to power as part of a coalition in 2012, Georgian Dream has won consecutive parliamentary and local elections deemed competitive and well-run by international observers—including representatives of the OSCE and NATO.

The party currently occupies 90 of the150 seats in parliament, a majority roughly similar to that won by the Conservative Party in the UK or the coalition supporting President Emanuel Macron in France—far from the thumping dominance of a single-party state. Even government critics accept that the opposition’s failure at the polls—the United National Movement (UNM), the largest opposition party, garnered around half as many votes as Georgian Dream in 2020—stems more from chronic infighting and lack of popular appeal than electoral manipulation or dirty tricks.

A recent poll by the respected Institute of Social Research and Analysis, conducted after the draft foreign agent bill was already introduced, found that if parliamentary elections were held tomorrow, only 9.6 percent of respondents would vote for the UNM, against 31.4 percent for Georgian Dream.

With the UNM’s electoral prospects looking dim, civil society groups and the country’s vast network of some 10,000 NGOs have become the de facto centers of opposition. Unlike the voluntary sectors in the US, the UK, and Europe, which are sustained by domestic philanthropy and volunteers, almost 90 percent of Georgia’s NGOs are foreign funded, according to recent estimates; in fact, most receive no domestic funding at all.

“Civil society in Georgia cannot survive, essentially, without Western support,” said Professor Stephen Jones, director of the Program on Georgian Studies at Harvard University. “In part, that’s because Georgian civil society organizations are not very well connected with ordinary people’s needs in Georgia. They are somewhat isolated from Georgian society.”

Unlike their Western equivalents, Georgian NGOs are widely seen as a vehicle for social advancement. Since the collapse of the USSR, there remain relatively few economic opportunities for the educated middle classes that constituted the country’s intelligentsia. The median monthly wage for teachers and healthcare workers stands at below USD 300. Yet for a certain kind of well-educated urban professional fluent in English and willing to learn concepts such as “capacity building,” joining a civil society organization would pay many times the median salary— in addition to a lifestyle of foreign travel and access to powerful mentors.

Ad Policy

“The NGO sector is the largest and most important lift into the upper middle class,” says Almut Rochowanski, a feminist activist focused on resource mobilization for civil society in Georgia and other former Soviet states.

According to Rochowanski, an entry-level NGO job for a recent university graduate can pay between $600 and $800 per month, with senior leadership receiving as much as $60,000–70,000 per year. A key reason that civil society is so against the foreign agent law, she believes, is that “they want to protect their rents.”

Another unusual feature of Georgia’s civil society and NGO sector is its high level of partisanship and near-total hostility to the elected government. “Civil society organizations in places like the UK or Europe generally have good relationships with the state,” said Jones. “It is a sort of basic understanding of Western democracy, that you’ve got to have some integration and cooperation between civil society and the state in order for it to function. This is not the case in Georgia.”

Examples of highly inflammatory language abound in the pronouncement of even the largest and most mainstream NGOs. This week, the Georgian branch of Transparency International released a statement describing the law as “an attempt to establish Putin’s rules in Georgia” and “a betrayal of all our ancestors and compatriots.”

In April, Georgia’s largest independent media organizations released a joint statement opposing the foreign agent law that claimed the Georgian Dream–led government “wants to rule the country by subjugation and control, suppression and expulsion, lies and demagoguery.” Giorgi Khveleliani, the founder of Gamziri, which bills itself as a “nonpartisan civic platform promoting EU values,” used Twitter to call on the West to “impose heavy sanctions” on Georgian Dream in response to the passage of the law.

In fact, there does not appear to be a single major foreign-funded civil society or media organization that is not fervently opposed to the elected government. “The entire ecosystem is against them,” says Sopo Japaridze, a labour activist based in Tbilisi. “And the NGOs have more power and influence than the government does internationally.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

It is difficult to imagine any government tolerating such a state of affairs without attempting to ensure that unelected and lavishly foreign-funded organizations do not exert outsize influence on domestic politics. “Most Americans would consider it absolutely intolerable if foreign institutions, especially ones linked to foreign states, played the leading part in funding de facto political groups within the U.S,” write Artin DerSimonian and Anatol Lieven of the Quincy Institute.

Despite popular associations with repressive regimes, numerous democracies have or are considering similar foreign agent laws designed to increase the transparency of civil society groups and reduce meddling from countries such as Russia and China.

In addition to the United States, which pioneered the field with Foreign Agent Registration Act (enacted in 1938), they include Australia, Finland, and Israel, as well as EU member states Hungary and Slovakia. Ironically, the EU, which has been the fiercest critic of the Georgian law, is itself currently drafting a directive that envisages a registration regime for foreign-funded media and political organizations. Shalva Papuashvili, the speaker of the Georgian parliament, claimed that much of the Georgian law’s language was borrowed from the European Commission’s draft directive.

Yet, says Japaridze, the protesters do not see Western-funded groups as foreign agents. “The only foreign agents possible in their eyes are Russian ones. They don’t care about losing any sovereignty or autonomy to Europe. They are actively asking Europe, ‘Please intervene in our domestic issues.’”

Then there is the matter of the protesters themselves. Portrayed in the Western media as the authentic voice of the Georgian people, these mostly young, urban, liberal, and highly educated men and women are in fact political and demographic outliers in a society that skews rural, older and socially conservative, one in which the 91-year-old Patriarch Ilia II of the Georgian Orthodox Church enjoys the highest popularity rating of any public figure, at nearly 90 percent.

The protesters’ disconnect from the Georgian mainstream is evident not just in the profusion of English-language signs (and American flags) at the protests (few Georgians over the age of 30 or living outside Tbilisi speak English) but also in their outspoken support for liberal values such as LGBTQ rights.

Indeed, recent legislation to ban the public promotion of homosexuality—ostensibly modeled on Russia’s notorious “gay propaganda” law—is widely cited by protesters as evidence of Georgian Dream’s antidemocratic instincts and pro-Russian drift. Yet it is more likely to have been driven by populism: A 2022 poll found 75 percent of Georgians opposed to gay marriage, with over half of respondents stating that LGBTQ people “should be legally prohibited from having the right to assemble and express themselves.”

Critically, the protesters’ simplistic view of European values and identity as homogenously socially liberal and pro-American elides vast differences between member states. There are many ways to be European, as shown by Hungary and Slovakia, who, like Georgia, combine strong European identities with socially conservative beliefs and a refusal to sever ties to Russia. Seen in this light, Georgia Dream’s brand of politics is not necessarily incompatible with membership of the bloc, particularly as right-wing and populist parties are now on the march even in traditionally liberal countries like the Netherlands.

In the tense aftermath of the law’s passage, veto, and expected revote in the coming days, opponents refuse to give up the streets. Emboldened by the support of Western politicians, foreign-funded NGOs and Georgian Dream’s political enemies, they may find a Ukrainian scenario irresistible.

“The opposition knows that they can’t win an election,” says Rochowanski, “so they want to do regime change instead.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to reflect events over the weekend, including the law’s veto.

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that moves the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories to readers like you.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

Thank you for your generosity.

Vadim Nikitin

Vadim Nikitin is a Murmansk-born, London-based Russia analyst and financial-crime specialist. His commentary and book reviews have appeared in The Guardian, The New York Times, and Dissent.

More from The Nation

Corrupt insurrectionists have no place on the Supreme Court.

Jeet Heer

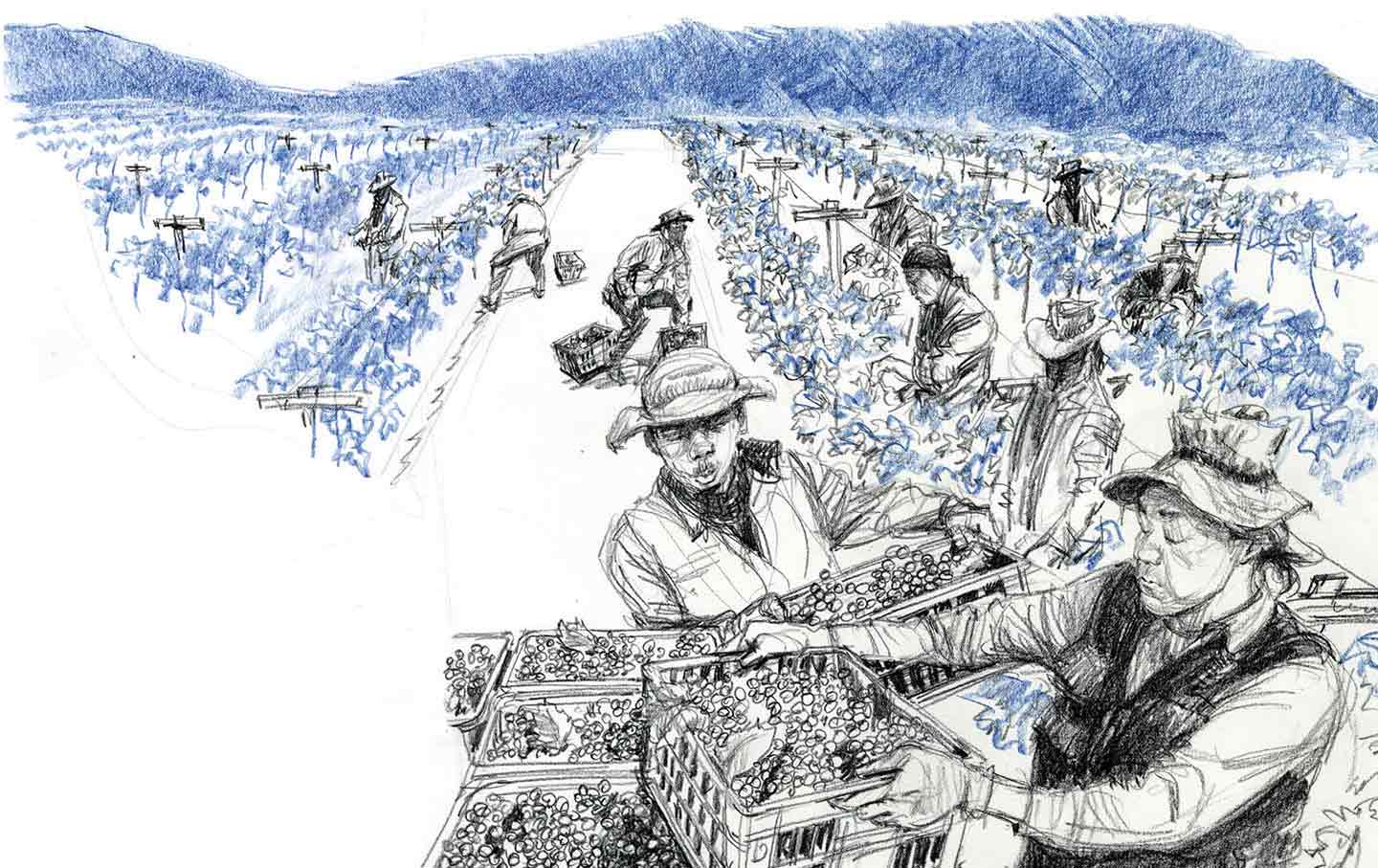

In April 2023, the community learned that an Israeli real estate company would soon construct a hotel on one-fourth of their land. “Progressively, we will lose everything.”

StudentNation

/

Joshua Yang

Manee Jirchat was one of the 31 Thai laborers kidnapped by Hamas on October 7. This is his story.

Feature

/

Timothy McLaughlin

In two decades, the ICC has never indicted a Western official. But a warrant may be coming for Benjamin Netanyahu.

Reed Brody

[ad_2]