This article contains descriptions of mental illness, alcohol addiction and suicidal ideation.

[ad_1]

Early one morning in February 2023, before the sun rose over Phoenix, Ravi Coutinho went on a walk and, for a brief moment, thought about hurling his body in front of a moving bus. He had been feeling increasingly alone and depressed; anxious and unlovable; no longer sure if he was built for this world.

Several hours later, Ravi swiped open his iPhone and dialed the toll-free number on the back of his Ambetter insurance card. After navigating the automated voice system, he was routed to a friendly, fast-talking customer service rep with a slight foreign accent. His name was Giovanni.

“How can I help you today?” Giovanni asked.

“Hi, I am trying to find a psychiatric care provider,” Ravi said.

“So, you are looking for a primary care provider?” Giovanni asked.

“No,” Ravi replied, seeming confused. Ravi tried to clearly repeat himself. “Psy-chi-at-ric.”

“Psychiatric, all right, so, sure, I can definitely help you with that,” Giovanni said. “By the way, it is your first time calling in regards to this concern?”

Ravi paused. It was actually the sixth attempt to get someone, anyone, at Ambetter to give him or his mother the name of a therapist who accepted his insurance plan and could see him. Despite repeatedly searching the Ambetter portal and calling customer service, all they had turned up so far, he told Giovanni, were the names of two psychologists. One no longer took his insurance. The other, inexplicably, tested patients for Alzheimer’s disease and dementia and didn’t practice therapy at all.

“I’m a little concerned about all this,” Ravi said.

This had not been part of the plan Ravi had hatched a few months earlier to save his own life. Diagnosed with depression and anxiety, and living in the heart of Austin, Texas’ boisterous Sixth Street bar district, the 36-year-old former college golfer had become reliant on a dangerous form of self-medication.

His heavy drinking had cost him his marriage and was on the verge of destroying his liver and his livelihood. His therapist back in Texas had helped him understand how his mental illnesses were contributing to his addiction and vice versa. She had coached him through attempts to get sober.

He wanted to save his business, which sold dream vacations to golfers eager to play the world’s legendary courses. He wanted to fall in love again, even have a kid. He couldn’t do that when he was drinking a fifth of a gallon of liquor — the equivalent of nearly 17 shots — on any given day.

When all else had failed, he and his therapist had discussed a radical move — relocating to the city where he’d spent his final years of high school. Phoenix symbolized a happier and healthier phase. They agreed that for the idea to work, he needed to find a new therapist there as quickly as possible and line up care in advance.

Ravi felt relieved when he signed up for an insurance plan right before the move. Ambetter wasn’t as well known as Blue Cross Blue Shield or UnitedHealthcare. But it was the most popular option on HealthCare.gov, the federal health insurance marketplace, covering more than 2 million people across the country. For $379 a month, his plan appeared to have a robust network of providers.

Frustrating phone calls like this one began to confirm for Ravi what countless customers — and even Arizona regulators — had already discovered: Appearances could be deceiving.

After misunderstanding Ravi’s request for a therapist, Giovanni pulled up an internal directory and told Ravi that he had found someone who could help him.

It was a psychiatrist who specialized in treating the elderly. This was strange, considering that Giovanni had asked Ravi to verify that he was born in 1986. “I mean, geriatric psychiatry is not …” Ravi responded, “I mean … I wouldn’t qualify for that.”

Annoyed but polite, Ravi asked Giovanni to email the provider list on the rep’s computer. He figured that having the list, which he was legally entitled to, would speed up the process of finding help.

But Giovanni said that he couldn’t email the list. The company that ran Ambetter would have to mail it.

“What do you mean, mail?” Ravi asked. “Like physically mail it?”

Ravi let out a deep, despondent sigh and asked how long that would take.

Seven to 10 business days to process, Giovanni responded, in addition to whatever time it would take for the list to be delivered. Ravi couldn’t help but laugh at the absurdity.

“Nothing personal,” he told Giovanni. “But that’s not going to work.

“So I’m just gonna have to figure it out.”

This baffling inability to find help had tainted Ravi’s fresh start.

In the weeks before the call with Giovanni, Ravi had scrolled through Ambetter’s website, examining the portal of providers through his thick-rimmed glasses. He called one after the next, hoping to make an appointment as quickly as possible.

Of course, it was unreasonable to expect every therapist in Ambetter’s network to be able to accept him, especially in a state with an alarming shortage of them. But he couldn’t even find a primary care doctor who could see him within six weeks and refill his dwindling supply of antidepressants and antianxiety meds.

Days before he was supposed to move to Phoenix, he texted friends about his difficulties in finding care:

“Therapists have been 0-4.”

“Called ten places and nothing.”

“The insurance portal doesn’t know shit.”

Ravi didn’t know it, but he, like millions of Americans, was trapped in a “ghost network.” As some of those people have discovered, the providers listed in an insurer’s network have either retired or died. Many other providers have stopped accepting insurance — often because the companies made it excessively difficult for them to do so. Some just aren’t taking new patients. Insurers are often slow to remove them from directories, if they do so at all. It adds up to a bait and switch by insurance companies that leads customers to believe there are more options for care than actually exist.

Ambetter’s parent company, Centene, has been accused numerous times of presiding over ghost networks. One of the 25 largest corporations in America, Centene brings in more revenue than Disney, FedEx or PepsiCo, but it is less known because its hundreds of subsidiaries use different names. In addition to insuring the largest number of marketplace customers, it’s the biggest player in Medicaid managed care and a giant in Medicare Advantage, insurance for seniors that’s offered by private companies instead of the federal government.

ProPublica reached out to Centene and the subsidiary that oversaw Ravi’s plan more than two dozen times and sent them both a detailed list of questions. None of their media representatives responded.

In 2022, Illinois’ insurance director fined another subsidiary more than $1 million for mental health-related violations including providing customers with an outdated, inaccurate provider directory. The subsidiary “admitted in writing that they are not following Illinois statute” for updating the directory, according to a report from the state’s Insurance Department.

In a federal lawsuit filed in Illinois that same year, Ambetter customers alleged that Centene companies “intentionally and knowingly misrepresented” the number of in-network providers by publishing inaccurate directories. Centene lawyers wrote in a court filing that the company “denies that it made any misrepresentations to consumers.” The case is ongoing.

And in 2021, San Diego’s city attorney sued several Centene subsidiaries for “publishing and advertising provider information they know to be false and misleading” — over a quarter of those subsidiaries’ in-network psychiatrists were unable to see new patients, the complaint said. The city is appealing after a judge sided with Centene on technical grounds.

Even the subsidiary responsible for Ravi’s plan had gotten in trouble. Regulators with the Arizona Department of Insurance and Financial Institutions found in 2021 that Health Net of Arizona had failed to maintain accurate provider directories. The regulators did not fine Health Net of Arizona, which promised to address that violation. When ProPublica asked if the company had made those fixes, the department said in a statement that such information was considered “confidential.”

These were exactly the type of failures that Ravi’s mother, Barbara Webber, confronted as the head of an advocacy group that lobbied for greater health care access in New Mexico. From her Albuquerque apartment more than 300 miles away from her son’s his new, 12th-floor studio, she listened to Ravi vent about how hard it was to find a therapist in Phoenix.

Ravi was Barbara’s only child, and they had always been close. In the seven years since Ravi’s dad died, they’d grown even closer. They talked on the phone nearly every day. Barbara was used to supporting Ravi from afar, ordering him healthy delivery dinners, reminding him to drink enough water and urging him to call crisis hotlines amid panic attacks. But when Ravi crashed at her apartment while waiting to move to Phoenix, she saw more of his struggles up close. At one point, she called 911 when she feared for his life.

Despite her desire and ability to help him, Ravi didn’t want to stay with his mom for any longer than necessary. He didn’t want to feel like a teenager again.

Barbara understood her son’s desire for independence, and when he first encountered insurance barriers, she drew from her expertise and coached him through ways to try to get past them. But by the middle of February, a few days after Ravi settled into his new place, there was no good news about his mental health care. She felt the need to step in.

So, she called Ambetter to try to get better information than what Ravi was looking at online. But Khem Padilla, a customer service rep who seemed to be working at a call center overseas, couldn’t help her find that information. She then asked Padilla to send referrals to therapists.

When Padilla followed up, he only sent phone numbers for mental health institutes, including one that exclusively served patients with autism. “I wish that everything will work together for you,” Padilla wrote in an email to Barbara and Ravi on what happened to be Valentine’s Day, “and [don’t] forget that you are Loved.”

Loneliness is one of the strongest forces for triggering a relapse in someone addicted to alcohol, and Ravi’s early days in Phoenix provided a dangerous dose.

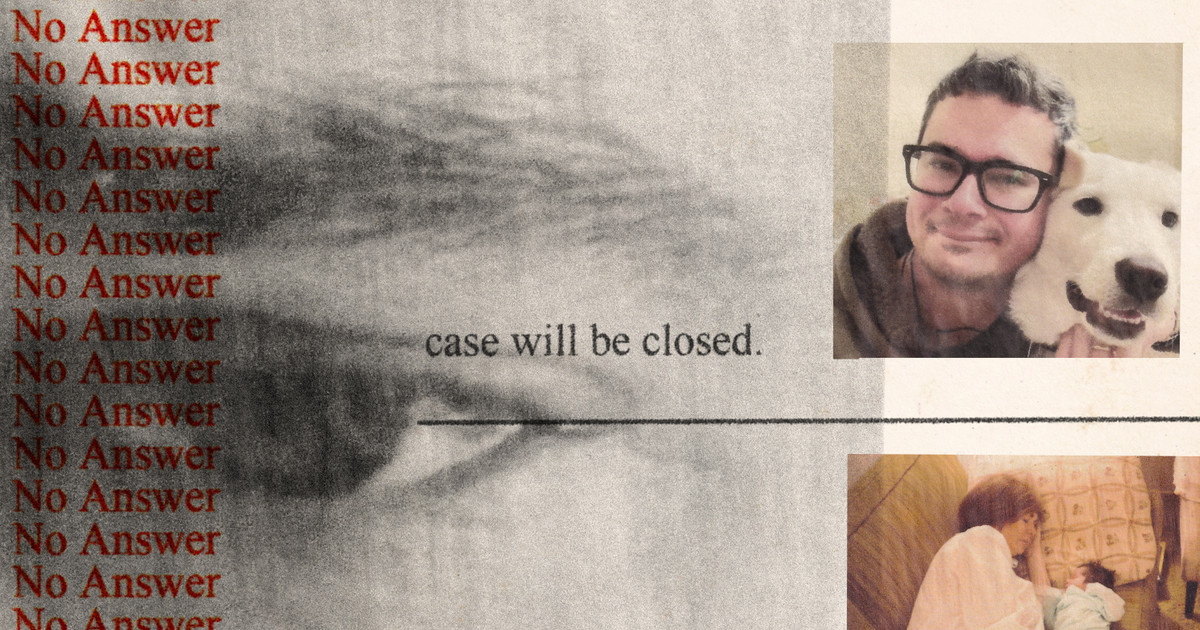

His old friends were often busy with work and family. He hadn’t found his way to a new Alcoholics Anonymous group yet. And he struggled to find matches on dating apps. (“Phoenix Tinder is a wasteland,” he told one friend.) His only consistent companion was Finn, a half-Great Pyrenees with a thick coat of fluffy white hair, whom he took on long walks around the city. “His unconditional love brings me so much joy,” he’d told his mom.

Alone in his apartment with Finn, vodka within reach, Ravi felt guilty about calling his loved ones for help. Even though his mom and his friends would pick up the phone at just about any hour, Ravi hated the idea of bothering them.

But he couldn’t resist after he hung up with Giovanni, the customer service rep. That afternoon, Feb. 22, he fired off a frustrated text message to his mom.

“How is it this hard?!” Ravi seethed.

Barbara’s next move was to reach out to a member of her nonprofit board who happened to work for a Centene company. The board member helped pull strings in late February to get Ravi a care manager, a person who works for the insurer to help patients navigate access to providers. But not even his new care manager, Breona Smith, a licensed professional counselor based in Arizona, could connect him to a therapist.

She spent 16 minutes calling in-network providers to check if they could see him. Four couldn’t. One could. Instead of calling more, she sent along a single therapy referral. When Ravi called that office, the staff had to verify if they accepted Ambetter. But Ravi never heard back.

Smith did get him a referral for a psychiatric nurse practitioner who could refill his meds; he first saw him one month into his move. Ravi hoped that the office might be able to refer him to a therapist, but none of the three providers it ultimately passed along took Ambetter. One of them had stopped taking insurance a decade ago; another had only ever seen patients willing to pay cash.

Without therapy, Ravi’s descent took on a momentum of its own.

One day, he drank himself to sleep and woke up with a pillow full of blood from his nose. On another, he white-knuckled a version of do-it-yourself detox that caused violent vomiting.

A close friend from high school, David Stanfield, was watching it all unfold. Ravi had always made David feel like they could pick up where they’d last left things. But this new withdrawn person, who would break into a sweat on a crisp night in the 60s, was a far cry from the guy he once knew.

Ravi was beginning to remind David of his brother-in-law, who had died of a drug overdose a few years earlier. So when Ravi sent a series of distressing texts, indicating that he had relapsed, David and another friend staged an intervention and took Ravi to the hospital.

But Ravi resisted rehab that didn’t come with therapy. He wondered what good another detox would do if it didn’t help him combat the root causes of his addiction. He was also worried that it would get in the way of his ability to work; Ravi was still booking some golf vacations through his business and figured he would have to surrender his phone during a rehab stay.

Instead, Ravi sated his withdrawals by feeding his body more alcohol, giving way to a March whirlwind of blackouts, massive hangovers and despondent texts to friends. When Ravi showed up to a baseball game looking pale and disheveled, a friend’s young son turned to his dad and asked: Is Ravi OK?

By early April, almost two months had passed since Barbara’s first call to Ambetter alerting them that Ravi was having trouble finding a therapist. Ambetter was obligated by state law to provide one outside of its network if Ravi couldn’t find one in a “timely manner” — which, in Arizona, meant within 60 days.

Within that span, its own records showed, he’d wound up in the emergency room seeking treatment for alcohol withdrawal and called a crisis line after he had thought about ending his life. Yet despite 21 calls with Ravi and Barbara, adding up to five hours and 14 minutes, the insurer’s staff had not lined up a single therapy appointment.

Smith called Ravi four times over two weeks, right as his mental health crisis worsened. When he didn’t respond, she closed his case on April 7. Smith did not respond to multiple requests for comment or to questions about what information she tried to share with Ravi on these calls.

As Ravi’s attempts to find a therapist slowed down, his descent accelerated.

There was the episode at a Phoenix Suns game when paramedics had to treat him for severe dehydration after he downed a bottle of vodka.

There was the time he left the dog food container open and Finn got extremely sick from eating a week’s worth of food.

As Ravi crossed into his fourth month in Phoenix, he sat alone in his parked Kia Forte, surrounded by nothing but the lonely quiet, and screamed at the top of his lungs.

Barbara didn’t expect to spend Mother’s Day with Ravi. But after he told his uncle that he was having visions again of jumping in front of a speeding bus, she boarded a last-minute flight to Phoenix and settled into his couch where she could watch him as he slept.

On the morning of May 13, she was roused by his flailing limbs. He was having a seizure. Paramedics rushed Ravi to the hospital, the second time in the past month and fourth since the year began. Doctors gave him benzodiazepines, Valium and Librium, to treat the seizures and anxiety caused by his alcohol withdrawal. “Mom,” Ravi told Barbara, “I don’t want to die.”

One kind of treatment suggested by hospital staff, an intensive outpatient program, seemed the best fit. It would allow Ravi access to his phone for his business purposes. But neither Ravi nor Barbara could get a list of in-network programs from Ambetter, nor could they find them in the portal.

As Ravi called every program he could locate in metro Phoenix, and failed to find a single one that took his insurance, Barbara decided to pester her board member again. (The board member did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

A few days later, someone with Centene provided the names of two in-network programs out of the dozens in Arizona. Only one offered the individual therapy Ravi was looking for.

That Friday, May 19, Barbara rode with Ravi to Scottsdale, where the intake staff at Pinnacle Peak Recovery drug-tested him. He tested positive for the benzodiazepines the hospital staff had administered following his seizure. Treatment programs sometimes restrict patients who test positive for those drugs because of the liability, experts told ProPublica. Pinnacle Peak Recovery’s staff urged Ravi to come back the following week. Barbara flew home, hopeful that Ravi would be admitted. (Pinnacle Peak Recovery did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

On Monday morning, Ravi wrote the date, May 22, on a sheet of paper. He tore it out of a notebook, held it up to the side of his face and took a selfie with it. It was a way of marking time as well as a milestone: the first day of his newfound, hopefully permanent sobriety.

Credit:

Courtesy of Barbara Webber

When he returned to Pinnacle Peak, however, he tested positive again. The second rejection hurt more than the first. Three days later, Ravi went back a third time; the drugs were still in his system. “I don’t know what else to do,” he told Barbara over the phone. “I am screwed.”

The answer of what else could be done was, unbeknownst to Ravi, buried in the fine print of his own insurance policy. Ambetter’s contract promised to find an out-of-network treatment program and make it available to Ravi, so long as Ambetter’s own employees decided that it was in his “best interest.”

Even though Barbara hadn’t read the fine print either, she had a sense that Ambetter could do more to help Ravi. So she pulled up the number of the last Centene employee she’d spoken with.

In a text message, Barbara expressed concern that the window to get Ravi help was closing. She was certain that, without more medical support ahead of admission to a treatment program, Ravi was bound to relapse. If that happened, Barbara pleaded, there was a good chance that he would have another seizure. She warned that he might even die.

Barbara awaited word on what to do next. She got no response.

The following morning, May 27, she drafted a message to Ravi. She described her visceral memory of his recent seizure — waking to the sound of his screams, pounding on his chest after his heartbeat briefly stopped, calling 911, uncertain if he would survive. “Those few minutes are seared into my soul and will go with me til the end of my days,” she wrote.

Barbara also wrote that she wanted nothing more than for Ravi to be around for the rest of her years. She promised to support him no matter what. If he kept going, he could find peace with Finn and find someone to love. But he had to keep going — not for her, not for Finn, not for his friends, not for anyone else. “I love you,” she wrote, “but you must love yourself.”

She hit send. Ravi didn’t reply right away, which was unusual.

An hour passed, then another. As the afternoon gave way to evening, Barbara called three times, unable to reach him. She tried to reach Phoenix’s 911 dispatch but couldn’t get through.

Not knowing what else to do, Barbara called David, whom Ravi had asked to be his local emergency contact.

David had grown deeply frustrated with Ravi for not getting the care he needed. And he was worried for his friend. He agreed to call 911.

A police dispatcher sent an officer to knock on Ravi’s door. The officer could hear Finn barking from the other side. When no one answered, the officer called David, letting him know that the police couldn’t enter the apartment without the building’s security guard, who wasn’t around right then.

Unsatisfied, David and his fiancée, Aly Knauer, drove over to Ravi’s. A security guard, who had just gotten back from his rounds, was reluctant to let them into the apartment at first. But after David and Aly explained the urgency, the guard relented. They headed up to the 12th floor and turned the corner toward Ravi’s apartment.

When the guard unlocked the door, Finn squeezed past and darted out. As Aly grabbed Finn, David peered inside, calling out his friend’s name. Four empty vodka bottles were strewn across the apartment. The Murphy bed was folded up against the wall. No one seemed to be there.

David glanced toward the window that frames the Phoenix skyline and felt a sense of relief. His friend might still be alive.

When he turned to leave, he looked again at the bed. He realized it was slightly ajar. As he leaned closer, to see why the bed hadn’t fully locked into place, David spotted something jutting out from the gap between the mattress and the wall: a lifeless foot.

We’re Investigating Mental Health Care Access. Share Your Insights.

ProPublica’s reporters want to talk to mental health providers, health insurance insiders and patients as we examine the U.S. mental health care system. If that’s you, reach out.

Expand

[ad_2]