[ad_1]

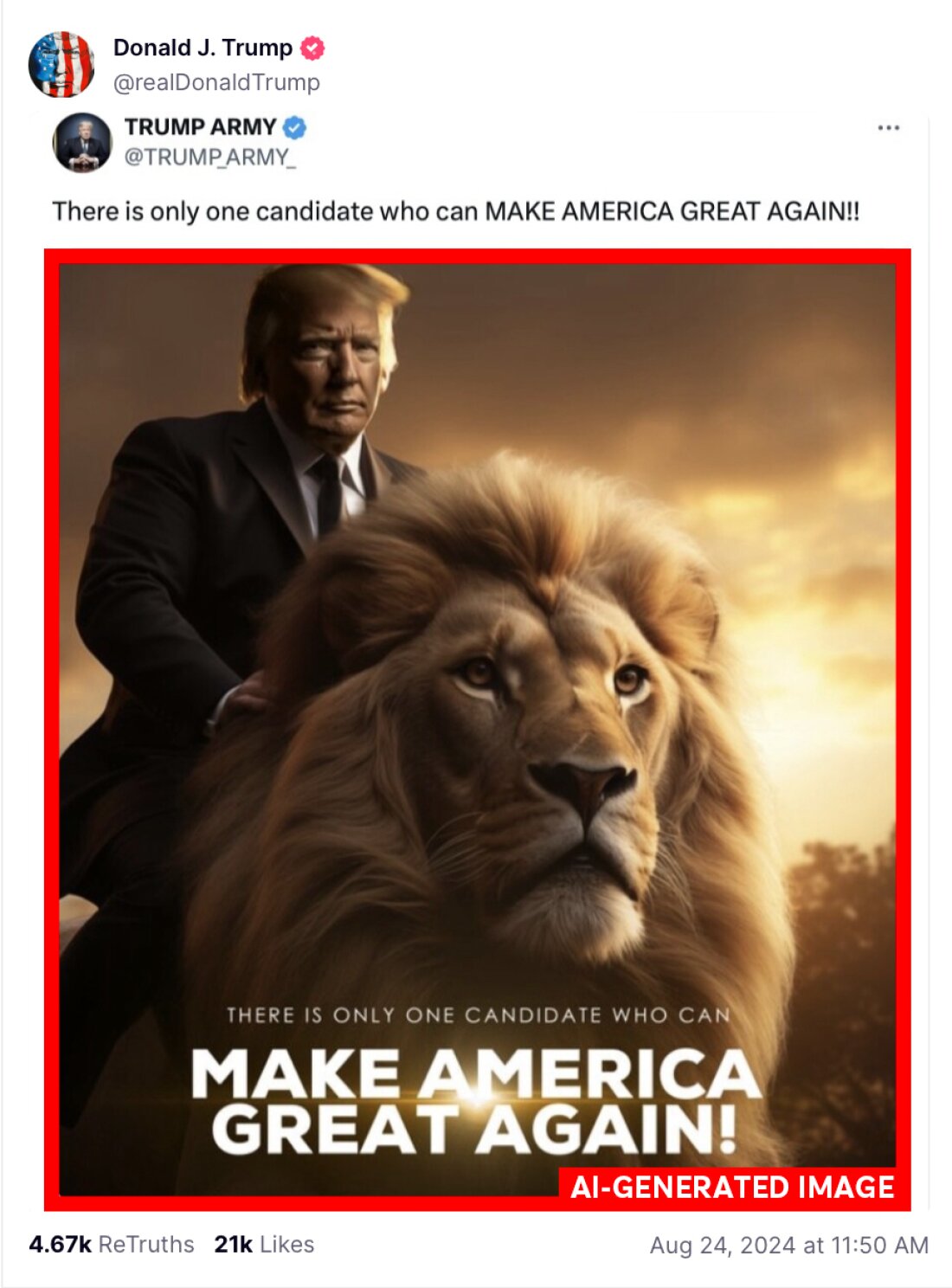

An AI-generated depiction of Donald Trump riding a lion. The image was first posted by a Trump supporter on X before Trump reposted the depiction on his Truth Social account. Trump has embracing reposting AI-generated images created by his supporters. NPR added the borders to the image to make clear the image was AI-generated.

@TRUMP_ARMY/screenshot by NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

@TRUMP_ARMY/screenshot by NPR

Last week, Donald Trump posted on Truth Social an artificial intelligence-generated image of Taylor Swift in an Uncle Sam outfit, falsely claiming she had endorsed him. The image is clearly fake and was accompanied by other depictions, some also apparently AI-generated, of young women in T-shirts reading “Swifties for Trump.”

In fact, Swift has not endorsed any candidate for president this year, and she endorsed Joe Biden over Trump in 2020.

Days later, Trump acknowledged the images weren’t real.

“I don’t know anything about them other than somebody else generated them, I didn’t generate them. Somebody came out, they said,’ Oh, look at this.’ These were all made up by other people,” he told Fox Business in response to a question about whether he was worried about a lawsuit from Swift.

“AI is always very dangerous in that way,” he continued, saying he has also been the subject of fakes implying he’s made endorsements he never did.

But in reality, Trump himself has repeatedly shared AI-generated content on social media in the latest example of how artificial intelligence is showing up in the 2024 election. The Trump campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Typically, Trump reshares posts from his supporters who have embraced new tools that make it easy to turn quick text descriptions into images, both plausible and fantastic.

An AI-generated image of Donald Trump playing guitar with a storm trooper character from Star Wars that was created by a supporter and posted on X. Trump’s supporters often create fantastical images of the former president in all kinds of settings that are shared on social media. NPR added the borders to the image to make clear the image was AI-generated.

@amuse/screenshot by NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

@amuse/screenshot by NPR

The subject of the images they create is often Trump himself: astride a lion, as a bodybuilder, performing at a rock concert with a Star Wars stormtrooper (really).

Other times, they mock or smear his opponents — like a recent fake image he shared of what appeared to Vice President Harris addressing a Soviet-style rally, complete with a communist hammer-and-sickle flag.

“One thing AI in particular is good at doing is taking ideas or claims being made in text and turning them into metaphorical representations,” said Brendan Nyhan, a political science professor at Dartmouth College. He says this is an AI-powered spin on the kind of memes, satire and commentary that are a staple of political communications.

“It’s chum for the folks who read a lot of political news online and tend to have slanted information diets,” he said.

An AI-generated image posted by former president Trump’s X account that depicts Vice President Kamala Harris delivering an address before a Soviet-style political convention. Trump’s supporters often generate images that denigrate and mock Trump’s opponents. NPR added the border to the image to make clear it was generated with AI.

@realdonaldtrump/screenshot by NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

@realdonaldtrump/screenshot by NPR

Trump supporters embrace AI for jokes, satire

Many of these AI images do not seem to be intended to be taken as literally true. They are often shared as jokes or parodies. Indeed, some of the fake Swifties for Trump pictures Trump posted were labeled as satire by their original creator.

They are aimed at an audience of people who are already Trump fans. That’s in keeping with Trump’s long history of resharing crude memes, bestowing belittling nicknames and making jokes at his rivals’ expenses.

“These images serve the function of reminding people which side they’re on, which politicians they like and don’t like, and so forth,” Nyhan said.

As AI tools have become widely available, worries have focused on their most malicious uses to deceive voters, like deepfakes of candidates, or photorealistic depictions of events that never happened.

Some of those worries have come to pass both in the U.S. and abroad — like the AI-generated fake robocall impersonating President Biden telling Democrats not to vote in New Hampshire’s primary.

There’s a lack of consensus among the companies behind AI generators over what guardrails should be in place. OpenAI, the maker of DALL-E and ChatGPT, prohibits users from creating images of public figures, including political candidates and celebrities. But the recently launched AI image generator on X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, appears to have fewer limits. When NPR tested it in mid-August, the tool produced depictions that appear to show Trump and Harris holding firearms and ballot drop boxes being stuffed.

Even more mundane uses of AI can also contribute to an environment where people trust what they see less and less, said Hany Farid, a professor at UC Berkeley who specializes in image forensics.

Trump himself has capitalized on that distrust, claiming falsely that the Harris-Walz campaign had used AI to fake a crowd at a recent rally. (The crowd, and photo in question, was real.)

“If you constantly see fake images and ones that look really compelling and really highly photorealistic … are you then less likely to believe it? Do you now start to just doubt everything?” Farid said.

AI-generated material could inflame tensions

Nyhan says while this type of AI content is unlikely to win over people who aren’t already aligned with Trump, it may inflame or even mobilize those who already hold the most extreme views. That’s why he worries about representations of violence, even ones that are obviously fake.

“People will, of course, encounter AI content online. Everybody will. But people who are encountering the most misleading or inflammatory content are likely to come from the fringes already,” he said. “These people are already polarized. Is it likely to polarize them more? It’s probably not going to change their vote. In what ways could this be harmful?”

There’s still plenty of time before Election Day for deceptive or misleading AI content to go viral, or, as some observers say is the greater risk, to be targeted at individual voters in private channels.

“The most pernicious types of deceptive synthetic media around elections are not even going to be efforts to discredit a particular candidate or make them look bad. … It’s going to be efforts to try to suppress voters and mislead voters and keep them from casting their ballots,” said Daniel Weiner, director of the elections and government program at the Brennan Center for Justice, a public policy nonprofit focused on voting rights.

He’s worried that could be used to make convincing false claims of threats or outages at polling places — and, ultimately, further erode trust in elections themselves.

“The biggest concern around AI is that it tends to amplify threats that result from other gaps and weaknesses in the democratic process,” he said.

[ad_2]