[ad_1]

Politics

/

August 30, 2024

But the hope I felt when she became the nominee has been curdling into despair over her refusal to allow a Palestinian to address the convention—and her continuing silence on Gaza.

In my first job out of college, in publishing, I learned the importance of flap copy—the text that introduces the book on its cover.

“If you get it right,” my boss said, “you’ll be amazed at how many reviewers will repeat exactly what you write.”

To my astonishment, this turned out to be true: If you wrote that a novel, say, was an unforgettable saga of three generations of women, lots of reviewers—not all but quite a few—would describe the novel as an unforgettable saga of three generations of women.

I thought of that lesson a lot over the past week, during and after the Democratic Convention.

The word on the cover, in this case, was “joy”—and I was astonished to see just how many pieces came out discussing this word. I saw it whooshing past on social media, including among my friends. I was a little embarrassed, as I was at my first job, when I realized how easily people could be manipulated. But I got it. I myself felt jaded, cynical—a lot of years have passed since I graduated from college, and I’ve gone through too many electoral disappointments to feel joy at the thought of most politicians—but I felt relief when Biden stepped aside. I felt hope when I thought that a second Trump presidency began to seem avoidable. And a week ago I felt optimism: I was excited by the selection of Tim Walz.

But as the days went by, the word “joy” made me cringe more and more—and not just because it was so overused. Every day during the convention, it became clearer that nothing was going to be said about the war on Gaza. It became clear that the Democrats, who were billing themselves as the party of anti-racism and inclusion, who even allowed anti-choice Republicans to speak, were not going to allow a single Palestinian or Muslim American to speak about a question of life and death. This was notable—given, as Jon Stewart said, that the convention “was only four nights, eight hours a night.” My optimism turned to amazement when I reflected on easy it would have been to do this. There are dozens of Muslim elected officials in the party. There are hundreds of people they could have found to mutter some anodyne, carefully vetted words about “pain” and “peace” and “both sides.”

Current Issue

For me and for the millions of Americans who care deeply about this horrible war, this refusal felt like contempt. And the tentative optimism I had felt at the beginning of the week started to curdle into emotions I didn’t want to feel—like despair, betrayal, rage. I wanted to keep these emotions to myself, because I’m aware that you’re not supposed to express them when demanding justice for marginalized groups. I remember so well how gay people were told not to “screech.” I remember the warnings to women not to be “shrill.” I remember how often black people are told not to be “angry.”

But over the course of the week, that’s how I started to feel.

A little screechy!

A little shrill!

A little angry!

And I knew I wasn’t the only one. Great majorities of Democrats and Americans are horrified by what is happening in Gaza. We all know that it wouldn’t be happening without the support of the administration in which the vice president is the second-in-command. Does she dissent from her boss in any way? If so, she might have used some language that indicated, however politely, her distance from him. And if she thought it was too risky to express another opinion, she could have at least allowed Palestinian Americans four or five minutes. Her refusal tells me everything I need to know about who she is. And who she isn’t.

You’ll often hear that foreign policy is not a priority of Americans. That may be true of some foreign policy issues, but what most people on every side of this issue understand is that Israel-Palestine is not really foreign policy. We all know that this war is made in America: On Monday, Israel received its 500th shipment of bombs from the United States. We know how many billions of dollars in aid we send Israel, without the slightest restriction. We have all seen the horrifying footage of schools and hospitals and refugee camps blown up, and we all know where the bombs are made. And we have also seen a Democratic administration—the same administration in which Kamala Harris is the vice president—refuse to go through even the rhetorical motions of condemning this unbelievable horror.

We know that Palestine is an American problem. It’s not like Rwanda, say, or Bosnia. You can say that the United States could have stopped those genocides, but not that the United States caused or supported them. We were not actually sending billions of dollars to the Hutus or the Serbs. We were not handing out machetes in Kigali as we are handing out 2000-pound bombs to Israel. Slobodan Milosevic was not, like Benjamin Netanyahu, getting standing ovations in the United States Congress.

Ad Policy

We also know that Palestine is a moral problem that goes to the heart of who we are—or who, at the convention, we were pretending to be. It is a problem that asks a harsh question: Do the principles to which the Democrats pay such joyous lip service, the principles that go to what we were always told was our nation’s very reason for existing, actually mean anything? After all, it’s not as if we didn’t hear about those principles at the convention. We heard a lot about freedom. We didn’t hear a lot about what that might look like for the Palestinians, or how many more decades they are expected to wait for it. We heard, ad nauseam, that Trump broke the law. We didn’t hear so much about how Israel’s constant defiance of international law—most recently, of a damning verdict from the International Court of Justice—makes a mockery of the entire idea of law and justice. We heard a lot about feminism, about the “glass ceiling” confronting powerful women like Kamala Harris and Hillary Clinton. We didn’t hear too much about the women of Gaza. We heard about “saving democracy.” We didn’t hear so much about bringing democracy to a trapped population that has no citizenship, no vote, and no civil rights.

It’s not that people didn’t want to talk about these things. It’s that they were not allowed to.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

All that was allowed was “joy.”

But joy was not the emotion I saw.

I saw self-righteousness, heartlessness. I saw people denouncing racism while cheering people responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of people who were killed because they belong to another “race.” I saw a woman who insists that she be allowed to finish her sentences forbidding certain people to speak. And when I saw that callousness and cynicism, I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to feel. But one thing was sure: aAt the start of the convention, I was planning to vote for Kamala Harris. I hadn’t wanted my own convention bounce—the cautious hope I felt at the beginning of the week—to turn into a lead balloon.

Now? I’m still open to voting for her. There is still time for her to earn the votes of people for whom this war is not a side issue. Because however much they try to shut down our voices, the Palestinian cause is not—can never be—a foreign cause. It is our cause, and we aren’t going away just because we are ignored. The vice president can’t rely on silencing people, or speaking of Palestinian suffering only in the passive voice. At a certain point, she is going to have to address this issue. I hope that when she does, she and the whole Democratic Party can feel a deeper sense of joy: the joy that comes from embracing a just cause, and from proving that freedom and democracy are not just empty words.

Can we count on you?

In the coming election, the fate of our democracy and fundamental civil rights are on the ballot. The conservative architects of Project 2025 are scheming to institutionalize Donald Trump’s authoritarian vision across all levels of government if he should win.

We’ve already seen events that fill us with both dread and cautious optimism—throughout it all, The Nation has been a bulwark against misinformation and an advocate for bold, principled perspectives. Our dedicated writers have sat down with Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders for interviews, unpacked the shallow right-wing populist appeals of J.D. Vance, and debated the pathway for a Democratic victory in November.

Stories like these and the one you just read are vital at this critical juncture in our country’s history. Now more than ever, we need clear-eyed and deeply reported independent journalism to make sense of the headlines and sort fact from fiction. Donate today and join our 160-year legacy of speaking truth to power and uplifting the voices of grassroots advocates.

Throughout 2024 and what is likely the defining election of our lifetimes, we need your support to continue publishing the insightful journalism you rely on.

Thank you,

The Editors of The Nation

Benjamin Moser

Benjamin Moser is a Nation contributing writer. For Sontag: Her Life and Work, he won the Pulitzer Prize. His next book, Anti-Zionism: A Jewish History, is coming from Doubleday in 2026.

More from The Nation

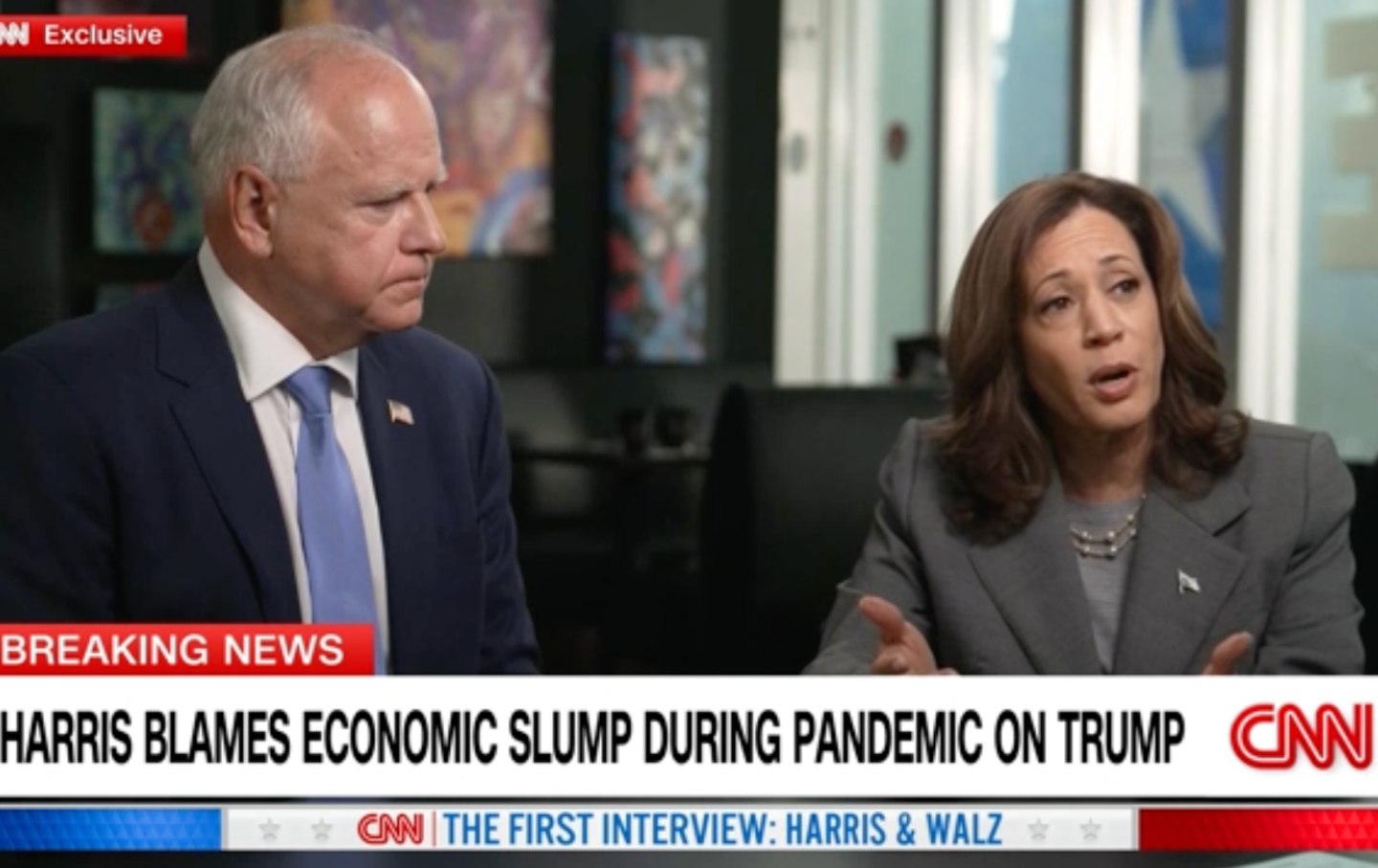

Harris and Walz held their own during an interview driven more by media-made controversies than substance.

Joan Walsh

The GOP’s new league of fringe figures tries to replicate the party’s winning formula of 2016. And it just might work again.

Jeet Heer

Should Kamala Harris win in November, her attorney general pick will be among her most critical cabinet appointments. Progressives should start organizing now.

Elie Mystal

Pamela Price, the Alameda County DA, is fighting a recall vote and to defend her unwavering refusal to over-criminalize young people.

Piper French

A lack of knowledge about the process—from registration to marking a ballot—is often the main barrier between youth and voting. “If young people sit it out, that will have an impa…

StudentNation

/

Aminata Gueye and Nikole Rajgor

We will have to overcome the MAGA project’s attacks on the electoral system even after the November election.

Sasha Abramsky

[ad_2]