Today, you likely often authenticate or pay for things with a tap, either using a chip in your card, or with your phone, or maybe even with your watch or a Yubikey. Now, imagine doing all these things way back in 1998 with a single wearable device that you could shower or swim with. Sound crazy?

These types of transactions and authentications were more than possible then. In fact, the Java ring and its iButton brethren were poised to take over all kinds of informational handshakes, from unlocking doors and computers to paying for things, sharing medical records, making coffee according to preference, and much more. So, what happened?

Just Press the Blue Dot

Perhaps the most late-nineties piece of tech jewelry ever produced, the Java Ring is a wearable computer. It contains a tiny microprocessor with a million transistors that has a built-in Java Virtual Machine (JVM), non-volatile storage, and an serial interface for data transfer.

Technically speaking, this thing has 6 Kb of NVRAM expandable to 128 Kb, and up to 64 Kb of ROM (PDF). It runs the Java Card 2.0 standard, which is discussed in the article linked above.

While it might be the coolest piece in the catalog, the Java ring was just one of many ways to get your iButton. But wait, what is this iButton I keep talking about?

In 1989, Dallas Semiconductor created a storage device that resembles a coin cell battery and uses the 1-Wire communication protocol. The top of the iButton is the positive contact, and the casing acts as ground. These things are still around, and have many applications from holding bus fare in Istanbul to the immunization records of Canadian cows.

For $15 in 1998 money, you could get a Blue Dot receptor to go with it for sexy hardware two-factor authentication into your computer via serial or parallel port. Using an iButton was as easy as pressing the ring (or what have you) up against the Blue Dot.

Indestructible Inside and Out, Except for When You Need It

Made of of stainless steel and waterproof grommets, this thing is built to be indestructible. The batteries were rated for a ten-year life, and the ring itself for one million hot contacts with Blue Dot receptors.

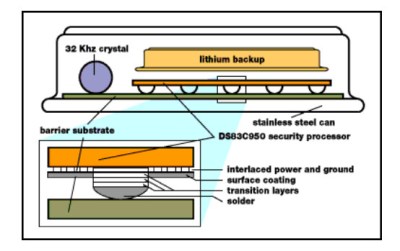

This thing has several types of encryption going for it, including 1024-bit RSA public-key encryption, which acts like a PGP key. There’s a random number generator and a real-time clock to disallow backdating transactions. And the processor is driven by an unstabilized ring oscillator, so it constantly varies its clock speed between 10 and 20 MHz. This way, the speed can’t be detected externally.

But probably the coolest part is that the embedded RAM is tamper-proof. If tampered with, the RAM undergoes a process called rapid zeroization that erases everything. Of course, while Java Rings and other iButton devices maybe be internally and externally tamper-proof, they can be lost or stolen quite easily. This is part of why the iButton came in many form factors, from key chains and necklaces to rings and watch add-ons. You can see some in the brochure below that came with the ring:

Check out the lofty language on this thing!

The Part You’ve Been Waiting For

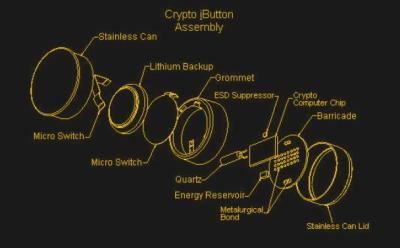

I seriously doubt I can get into this thing without totally destroying it, so these exploded views will have to do. Note the ESD suppressor.

So, What Happened?

I surmise that the demise of the Java Ring and other iButton devices has to do with barriers to entry for businesses — even though receptors may have been $15 each, it simply cost too much to adopt the technology. And although it was stylish to Java all the things at the time, well, you can see how that turned out.

If you want a Java Ring, they’re on ebay. If you want a modern version of the Java Ring, just dissolve a credit card and put the goodies in resin.