[ad_1]

July 3, 2024

Yet there is a resurgence of organizing by the left.

Technically speaking, it’s not flyover country. The passenger jets shooting overhead have taken off from Roissy, a town in the ninth constituency of the Val-d’Oise department that’s home to the Paris region’s sprawling Charles de Gaulle Airport. But once in a cab or aboard an express train to the capital city, few travelers probably know that they’ve momentarily passed through a political fault line, the type of place driving a realignment of France’s party system that could soon bring Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement national (National Rally, RN) to power.

Le Pen and her allies may now be on the verge of forming the first far-right government in France since the Vichy regime. On the backs of President Emmanuel Macron’s surprise dissolution of the National Assembly—a risky move to both restore authority after his party’s defeat in the June 9 European elections and “clarify” political allegiances, as the president has said—voters returned to the polls for the first round of snap elections on June 30.

The decision has turned into a major debacle for Macron, confirming the far right’s near-dominant position in French political life. The RN and its allies emerged on top in the first round with 33.2 percent of the vote, outdistancing the left-wing New Popular Front Alliance at 28 percent. RN candidates are in first place for 297 run-off races, with over a hundred second-place finishes. According to speculative seat projections, the far right is expected to secure the biggest bloc in the next National Assembly, possibly winning anywhere between 230 and 280 seats. Two hundred and eighty-nine votes are needed for an absolute majority.

In places like the ninth Val-d’Oise constituency—once a relatively humdrum seat, changing hands between the establishment parties of the center-left and center-right—Macron’s coalition has been quite simply blown off the map. On June 30, the New Popular Front Alliance, led by incumbent deputy Arnaud Le Gall of La France insoumise (France Unbowed, LFI), won just over 40 points, with 17,157 votes—roughly 4,000 votes ahead of RN cand0idate Agnès Marion. With over 70 percent of the electorate divided between the left-wing and far-right oppositions, the local Macronist candidate placed a distant third at 14.6 percent.

According to sources in Le Gall’s campaign, however, these results point to a very tight race in the second round. With the far right likely to absorb much of the vote from the other right-wing forces, they expect the fight over the seat to come down to a few hundred votes.

“This constituency is a prime example of what we’ve been predicting for years,” says Le Gall, who was first elected in 2022, replacing the Macronist candidate who had held the seat since 2017. “Once all the chips are down, it will be us or them.”

Current Issue

By “us or them,” Le Gall was referring to the hard-right nationalism of Le Pen, on the one hand, and the forces of the Popular Front. France’s leading left-wing parties—LFI, the Greens, the Communist Party, and the Socialist Party—agreed in June to a broad-based reform program, including a hike in the minimum wage, investments in public services, and a repeal of Macron’s 2023 increase in the retirement age. In 2022, Le Gall was elected with a 56-44 spread over the local RN candidate, a relatively safe margin that nonetheless spoke to the advances made by the far right in a seat situated so close to Paris. In a parliamentary vote that year that came on the heels of the presidential elections, the RN did outperform Marine Le Pen’s national second-round support at roughly 41.5 percent. The gap is now expected to be far closer, as the RN absorbs the remains of traditional suburban center-right voters, consolidating its hold on the broader French right.

It’s a duel that seems etched into the social geography of Le Gall’s district, which straddles the northern edge of the Paris urban area and an exurban, semirural hinterland. On the district’s southern end, towns like Gonesse and Goussainville mark arguably the last of the Paris-area banlieues. They are home to a predominantly working-class and multicultural community, including a considerable share of immigrants or their children and grandchildren. Dependent on low-wage service-sector jobs in the Paris area or in the logistical hub around the Roissy airport, a town like Goussainville is characteristic of the high level of economic insecurity in some of Paris’s suburbs, with the poverty rate approaching 29 percent, according to the latest study from Insee.

“The far right’s first victims are going to be in communities like this,” says Houari, an LFI activist who moved from Algeria in the late 1990s before gaining French nationality in the 2008. Although the party has walked back many of its past redistributive and social promises in a bid to improve ties with the business community, the RN has clung to the core of its racist, anti-immigrant platform. The party is promising to accelerate expulsions, end birthplace-based citizenship rights, and bar binationals from certain state jobs. Its hallmark proposition is the codification of “national preference” for things like access to employment, social services, and housing.

But one wonders if the fear of the far right, and everything that the Le Pen name carries with it, still has the same ability to mobilize voters in rejection. “There’s still the same old fear, because it would represent a major leap into the unknown,” said one Goussainville resident, who calls himself Le Commandant and works at a subcontractor for the national rail network. But what seems to have most relativized anxiety about the far right are the nationalist and anti-minority policies from mainstream political forces, including the sitting and soon to be lame-duck president. “Already with Macron and Darmanin [the hardline incumbent interior minister], France is about harassing immigrants and Muslims,” Le Commandan continued.

We were speaking on the sidelines of the open-air market in Goussainville days before the June 30 first round. This is one of Le Gall’s electoral strongholds, where he and LFI have developed deep roots with local activist networks and community leaders. And the electoral work and organizing has paid off: On June 7, 56.98 percent of Goussainville voters supported the NFP. “Marine Le Pen appeals to people in villages far away from places like Goussainville, but she has never actually come to see how people live here,” says Houari.

But in a district like Le Gall’s, the zones of far-right strength are not that remote, in fact. The northern arc of the ninth Val d’Oise constituency is a shift into leafier small towns and villages. Wealthier than Goussainville or Louvres, it’s lower-middle-class bedroom communities like Chaumontel or Luzarches where National Rally has made major inroads among a formerly center-right electorate. Even in more solidly middle-class towns like Saint-Witz, home to many pilots and middle managers at firms like Air France, Le Pen’s local candidate emerged in first place in the June 30 first-round vote.

Ad Policy

Much is made in France of the rural-versus-urban divide. In a district like Le Gall’s, however, the two brush up together, making it into something of a microcosm of the national showdown between the two blocs vying to mark a break from the Macron era. And if this summer’s lightning campaign precluded the deeper work of going out to convince voters seduced by Le Pen, many of the problems facing the district as a whole ultimately stem from similar causes, whether that’s anxieties about purchasing power or insecure employment or the dearth of investments and access to public services.

“We’re on the wrong side of the 95,” said one young man in a housing project in Louvres, referring to the zip code of the broader Val-d’Oise department, which stretches from wealthier communities in the west to working-class and lower-middle-class towns in the ninth constituency furthest to the east.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Like much of the “big crown” departments in Paris’s outer suburbs, the district has seen a rapid population expansion in recent decades, predominantly from people moving out of areas closer to the metropolitan core. What hasn’t followed is investment and public planning: The district contains only one hospital with an emergency room—in an area with roughly 110,000 residents. Declining standards of living for teachers has meant a dearth of staffing at public schools—a habitual problem to manage with local school districts for Le Gall’s constituent services. The main public transportation option to central Paris, the RER D, reaches through towns like Goussainville and Gonesse, although it is notoriously prone to delays and halts in service. The “Grand Paris” expansion of the metropolitan transport network does plan for one stop in Gonesse, but it’s still unclear if a future line 19 through the Val-d’Oise will traverse the district.

The name of the game for Le Gall is turnout. This goes for France more broadly, of course, with the rise of the far right in recent decades running parallel to a dramatic falloff in electoral participation. These snap elections look set to mark a significant break in the trend, with upwards of 66.7 percent of voters turning out for the first-round vote. Nationally, that’s the highest level of voter participation since 1997, and nearly 20 percent higher than the 47.5 percent who made it to the polls in 2022 parliamentary elections.

The problem is especially marked in a district like Le Gall’s, which has long been a competitor for French records in abstention rates. Only 37.8 percent of local registered voters turned out in the 2022 first round, a figure that leaped to 60.28 this year. Le Gall has a simple appeal to the voters he meets: “If people vote, we can crush them. And we have to crush them.” Yet one of the revelations of Sunday’s vote is that increased participation has benefited candidates on the right as well. The question going into the second round is if further abstentionists can still be brought out, as the NFP could find it difficult to fall back on a reservoir of voters from other parties.

Agnès Marion, the RN’s candidate in the ninth, has mounted a relatively light-impact campaign. Then again, the strength of the far right has never been in grassroots organization. What has for years given the former Front national its momentum is contextual: a flattened, bowdlerized political landscape; centrist political forces or media organizations that set the agenda around its securitarian and identarian obsessions. Then there’s the increasingly common equivocation between the left-wing and far-right “extremes,” in the plural—with many in the political center hesitant to call to support the NPF in possible runoffs.

By comparison, the left’s best strength here is its presence on the ground. Le Gall is a talented retail politician, distributing flyers in central Goussainville, or shaking hands with familiar faces at the city’s fifth annual African Nations’ Cup youth soccer tournament. His campaign has knocked on thousands of doors, with packs of activists fanning out over the district since June 9.

Le Gall also can benefit from the work done over the last two years as an incumbent. Though the left-wing opposition was in no position to get its laws passed, Le Gall worked alongside local social movements and groups, attending picket lines with striking workers at the Charles de Gaulle airport, helping constituents seeking the security clearance required to get hired, or serving as an intermediary for parent associations. LFI’s local networks helped organize Goussainville’s rally this winter for a cease-fire in Gaza.

One boon for organizing comes with the hope that local leaders will boost the get-out-the-vote campaign, sending out messages in WhatsApp groups, between members of local football clubs, or text chats between mothers in housing projects. “Whatsapp networks are where people really get information and communicate locally,” says Yssa, one of Le Gall’s important local relays with a long history in local social movements and organizing.

“It’s not clientelism,” says Le Gall, dismissing the usual critique of LFI’s strength in the banlieues. “We’re mobilizing citizens. The dominant interests in the country want these people to not vote.”

Another crucial asset for Le Gall’s potential voters is Jean-Luc Mélenchon. A veteran left-wing figure and founder of La France insoumise, Mélenchon has developed a highly controversial reputation, with many on the center-left hoping he will withdraw from the political centrality he’s held in recent years. But in parts of Le Gall’s district and in many places of strong left-wing popular support, he’s something of an icon, attracting voters with a strong egalitarian message, a no-taboos critique of racism, police violence, and Islamophobia, and his party’s firm calls for a cease-fire in Gaza. “Tell him he’s a bandit,” the young man in Louvres said, when Le Gall told him that he’s a candidate with Mélenchon’s party. “Tell him that the guys in Louvres thinks he has real balls.”

“Be honest, are these elections rigged?” he asked Le Gall. “The day of the vote it isn’t,” the candidate replied. “It’s what happens long before and beyond the polling booth that can make the difference.” That math, as the two know, is dramatically tipping in Le Pen’s favor.

Thank you for reading The Nation

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply-reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Throughout this critical election year and a time of media austerity and renewed campus activism and rising labor organizing, independent journalism that gets to the heart of the matter is more critical than ever before. Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to properly investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories into the hands of readers.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

More from The Nation

Last year recorded 162,000 conflict-related deaths, Ukraine and Gaza account for nearly three-quarters of deaths. Barcelona street art.

OppArt

/

Andrea Arroyo

The feud between the Dutertes and the Marcoses could have dire consequences for the cold war between China and the United States.

Feature

/

Walden Bello

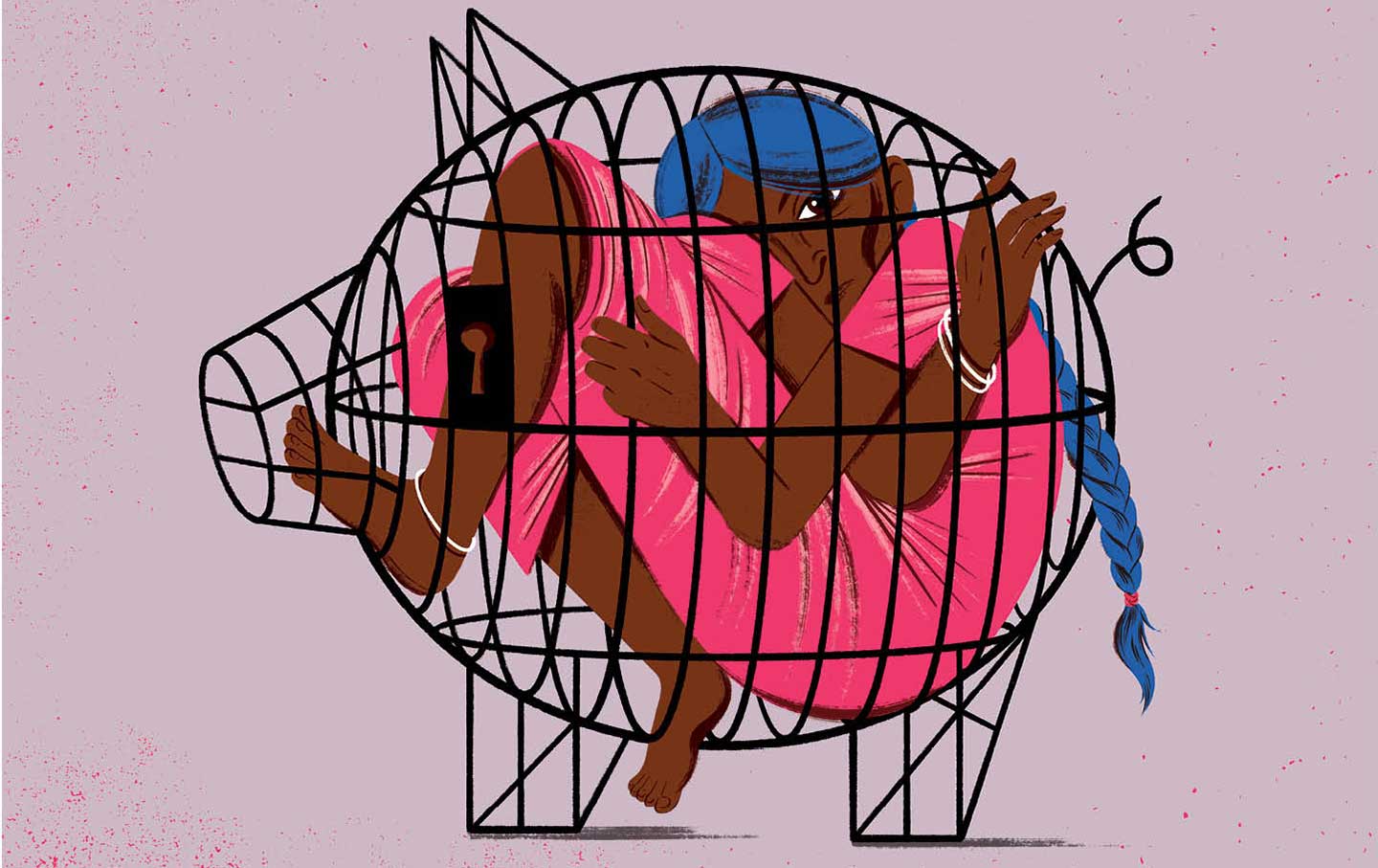

Microfinance has been touted as a miracle cure for poverty in the global south. The reality has been a lot messier.

Feature

/

Mara Kardas-Nelson

Is the Netanyahu administration planning to rake in cash on the site of an ethnic cleansing?

Razing Hell

/

Kate Wagner

[ad_2]