[ad_1]

Newsprint pages flitting in the wind, a scatter of pins, a cracked mirror, an exposed garter belt on a blurred body, a blinking eye. Kitten heels dancing the Charleston, painted brows and a string of pearls, a masked woman arching her neck for a kiss, a trio in striped tank tops tossing oversized die across the floor.

The disjunctive dreamscape that comprises Le retour à la raison (Return to Reason), a cinematic quartet of May Ray’s early silent films, beguile and bemuse in equal measure. Recently restored to 4K definition, the experimental shorts vividly reflect the era’s zeal for art and its ability to embrace and adapt new technologies. Born in 1890 in Philadelphia to Russian Jewish immigrants, Ray, best known for making photography an art form, reluctantly applied his artistic vision to the commercial realm of fashion. Filmed in Paris in the 1920s, his Return to Reason series anticipated the extent to which the motion picture would inform how we curate and call up memory, excavating the depths of the subconscious.

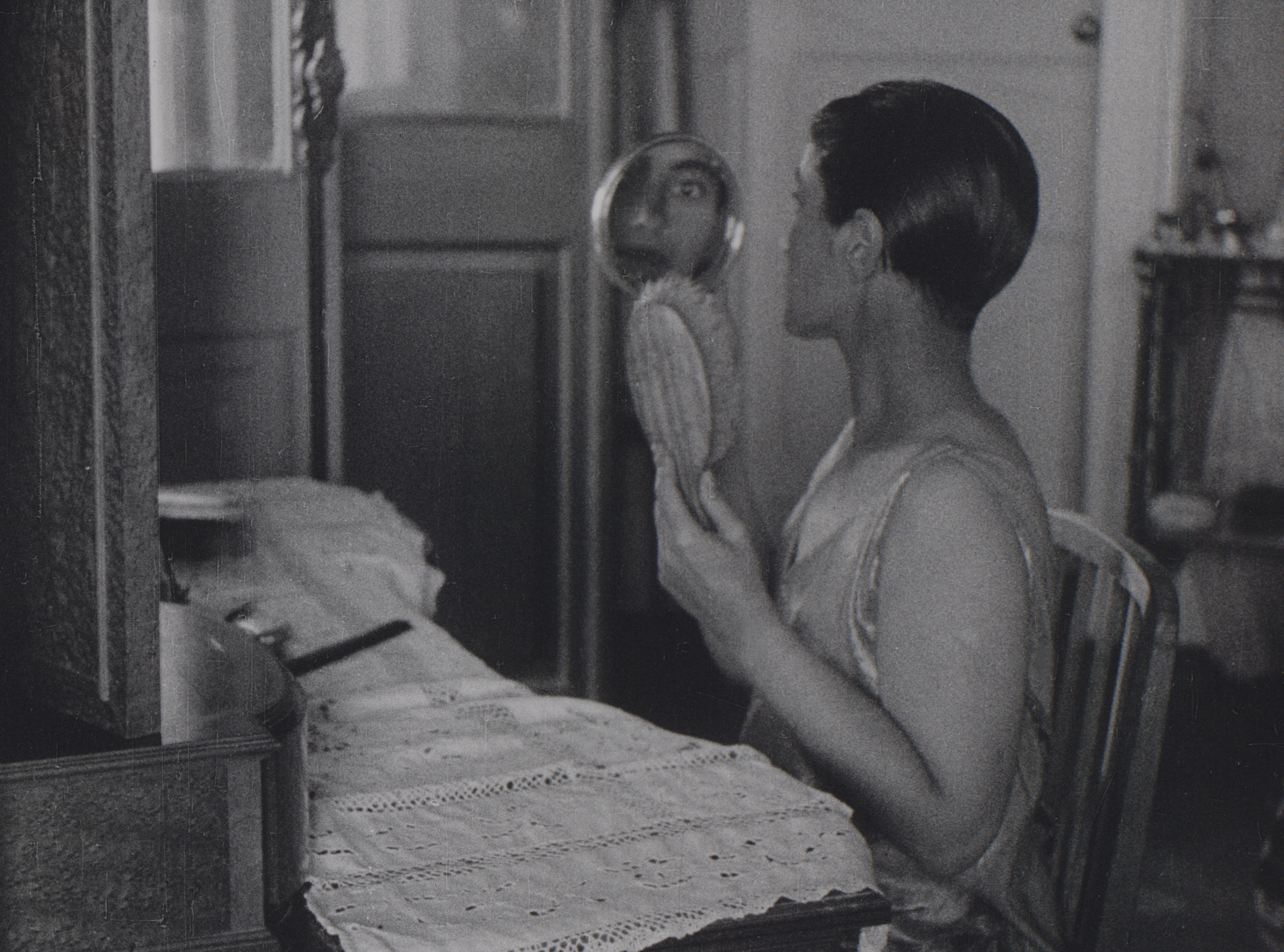

Though only one of the films — “Emak Bakia” (“Leave Me Alone” in Basque) — is overtly labeled a “cinépoéme,” all four shirk narrative for a sublime rapture of imagery, warping traditional perspective and rupturing any conventional sense of character or climax. In “L’étoile de mer” (“The Starfish”), a woman and man prepare for a tryst in what seems to be a remote inn; a gelatin filter covers the lens to obscure both their likeness and partial nudity. A train speeds through a series of towns, a starfish becomes a glinting knife. Filmed primarily at a villa in France’s Basque region, “Emak Bakia” launches with an eye reflected in the camera’s lens, inviting our voyeurism. Fluttering shapes and graphics follow; from there, the camera hops onto a speeding motorcar, foreshadowing Dziga Vertov’s 1929 Man with a Movie Camera, succeeded by shots of a woman applying lipstick, an ocean at tide, and a pig, interspersed with cameos of Ray’s own modernist sculpture.

“Le retour à la raison” (“Return to Reason”), only three minutes long and the most abstract, floods the eye with frenetic particles; salt and pepper, thumbtacks, and string are applied directly to the celluloid, segueing into the spinning lights of a carousel at night. While Ray’s investment in avant-garde experimentation was certainly serious, a playful humor dominates “Les mystères du château du dé” (“The Mysteries of the Castle of Dice”), where, as one intertitle reads, “a throw of dice will never abolish chance.” Wearing nets over their heads, a jocular group of pleasure-seekers take over a modernist home — doing handstands in the pool, tumbling from a swinging trapeze.

Three of the four films feature Jazz Age icon Kiki de Montparnasse, who clearly enjoys waggishly toying with the camera’s gaze, subverting Ray’s frequent fetishization of her body parts. “Women’s teeth are objects so charming,” reads an excerpt of “L’etoile de mer” (“The Starfish”) by Surrealist poet Robert Desnos, one of many lines that appear during the film of the same name, giving off a more droll than earnest tone.

Set to a drone-rock score from SQÜRL, the musical project of Jim Jarmusch and Carter Logan, who also produced the movie, these trippy films transport us to a time when the magic of film was palpable in every frame.

Man Ray: Return to Reason screens at the IFC Center (323 Sixth Avenue, Greenwich Village, Manhattan) through May 23, with a national rollout to follow.

Related

[ad_2]