[ad_1]

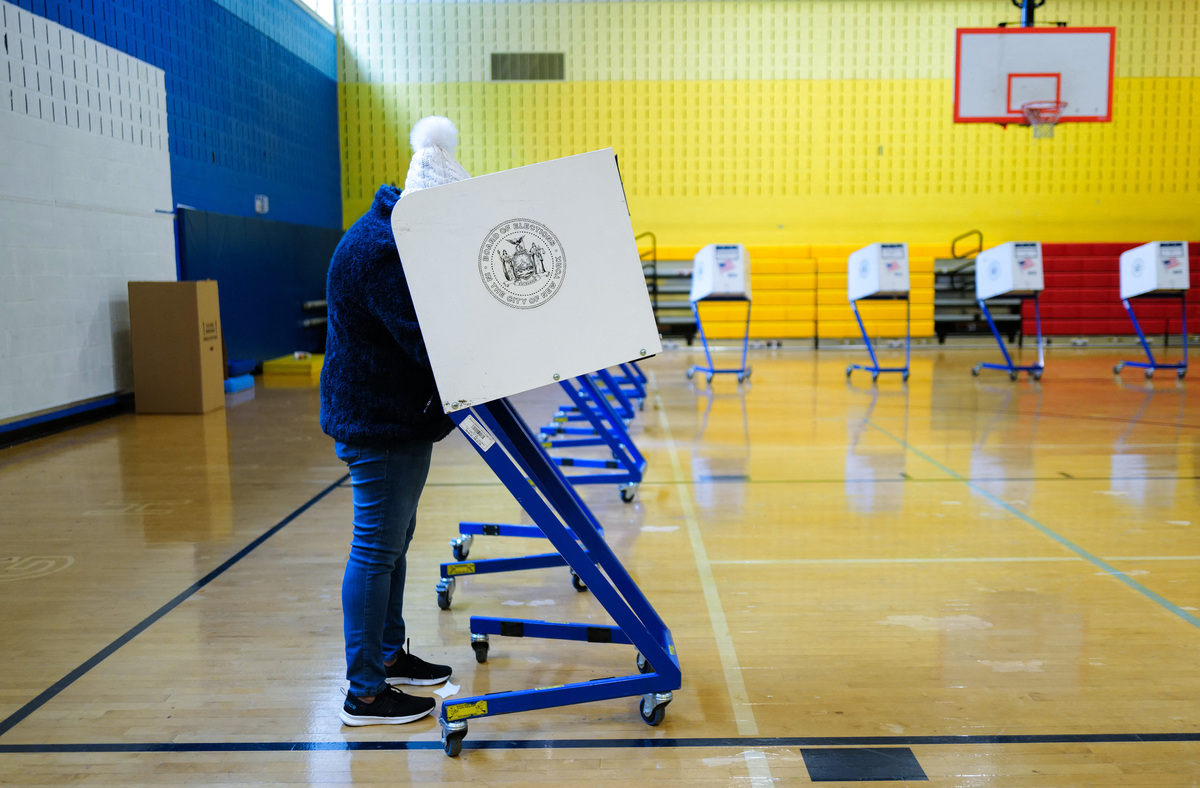

A person votes at a polling station in Manhattan during New York’s presidential primary on April 2.

Charly Triballeau/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Charly Triballeau/AFP via Getty Images

A person votes at a polling station in Manhattan during New York’s presidential primary on April 2.

Charly Triballeau/AFP via Getty Images

Elections in the United States are chronically underfunded.

It’s one of the few things voting officials across the political spectrum agree on.

In Kentucky, for instance, Republican Secretary of State Michael Adams said before he came into office in 2020, the state had not adjusted how much it gave to counties to support elections since the 1980s.

“We had election equipment that was nearing decertification,” Adams said. “We weren’t able to do the most basic things, like recounts.”

Estimates on exactly how much the country spends on democracy every year vary, but one recent report from MIT and the American Enterprise Institute found that local governments spend roughly the same amount to support voting as they do to maintain their parking facilities.

So when the U.S. Department of Homeland Security announced last year that it would require a portion of a multibillion-dollar grant program to go toward election security, much of the voting community celebrated — even if it was just a sliver of the money many experts say is ultimately needed.

“This new funding has the potential to provide meaningful support to our guardians of democracy,” elections experts Larry Norden and Derek Tisler of the Brennan Center for Justice wrote at the time. “It is also a meaningful statement from the federal government that it understands threats of physical violence against those who run our elections are a threat to our democracy itself.”

But NPR has learned that in many cases, the grant allocations did not go as planned.

Multiple election officials and experts told NPR that at least some portion of the money either did not actually go to reinforcing the country’s voting infrastructure, or was spent in a haphazard manner with little thought to what was most necessary ahead of a highly contentious presidential election that has many voting officials fearful for their safety.

“That money could be really significant in buying basic things like keycard access to make sure that nobody can get in to reach voting machines, or bulletproof glass,” Norden said, in an interview with NPR. “It’s disappointing that in some cases, election officials around the country didn’t feel like they got what they needed.”

A number of issues with the 2023 election grants, including a “redirect” back to policing

The money comes from an annual grant program, administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, which is meant to help state and local governments prepare for and prevent terrorism and disasters. For some of the grants, DHS designates priority areas to further target what the money is spent on, and in 2023, the agency designated election security as one of those priorities.

In total in 2023, DHS allocated more than $2 billion in preparedness grants, with at least $30.9 million supposed to go toward supporting election security.

It’s unclear exactly how much of that money actually went to what voting officials in those places would have deemed effective, but it’s clear that at least a sizable portion did not.

One state election official told NPR that they were not consulted by the emergency management coordinator in their state before the election security money was allocated, and instead were told how it would be spent just a few days before the deadline for the grant application. The official did not have permission to speak publicly, but spoke to NPR about their experience with the grant program on condition of anonymity.

After asking for months to be involved in the process, the week of the grant application deadline, the election official said they joined a call with their statewide emergency management coordinator who laid out their plans for the election security money.

The election official was most struck by one line item during the meeting: Tens of thousands of dollars were slated to be spent on cybersecurity risk assessments for local governments.

The only problem?

Those exact services are already offered to local governments by the federal government at no charge.

“They were completely duplicative of things we could get for free,” the official said.

But when that was brought up, the emergency management lead said it was too late to make changes to the proposals for the money.

One problem with the grant rollout, according to multiple government sources NPR spoke to, is that localities traditionally begin working on their DHS grant applications close to a year before they are due in the spring. But the federal government did not announce the election security requirement until late February — just a couple months before the application deadline.

FEMA officials say they can’t issue guidance until grant amounts are determined by Congress and signed into law by the president.

The cramped timeline coincided with the fact that the grant applicants often don’t have a working relationship with the local or state election administrators, says Kim Wyman, a former local election official who worked on election security issues with DHS until last year.

“These grants historically have been really focused on emergency management and law enforcement, so the people in those communities knew exactly when they were coming out, how to apply, how to submit those applications,” said Wyman, now a senior fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “Whereas a number of election officials were caught flat-footed because they’d never seen them before, weren’t aware of them.”

The election official who spoke to NPR on background said it was clear that the applicants in their state were trying to satisfy the election security requirement without actually adjusting how the money was spent. Another line item was a bomb training exercise that supposedly was to benefit election security, but when asked which election officials were invited to the exercise, the emergency management lead said none.

“It was a redirect,” the voting official said. “They took federal money that was supposed to go to election security, and put it towards policing.”

FEMA did not respond to questions from NPR about the grants, but it’s clear the agency is aware of the problem.

A Government Accountability Office report from earlier this year noted the difficult rollout of the new election security requirement.

In one instance, a locality fulfilled its election security obligation by purchasing “a single security barrier … which the grantee said is restricted to use for election security purposes only,” according to the GAO report.

The report authors spoke with 16 federal officials involved with distributing the grant money, and found that eight of them “had challenges” meeting the election security requirement. Among the listed reasons for that trouble were a “lack of subject matter expertise” and “absence of a regional need to address this issue,” seemingly implying there was no need for election security funding in those locations.

“That’s a preposterous response,” said the official who spoke to NPR about their experience with the grant process. “What that tells me is you didn’t try. You didn’t talk to anybody. You just sat there and waited for the phone to ring.”

Optimism for improvements going forward

A voter casts a primary ballot at a polling place in Atlanta on March 12.

Elijah Nouvelage/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Elijah Nouvelage/AFP via Getty Images

Last week, DHS announced this year’s preparedness grant total would be more than $1.8 billion, with a required spend of roughly $27.8 million on election security.

Generally, officials and experts NPR spoke with expressed optimism that voting officials would be more involved this time around.

“I think part of it was it was the first time it was happening. It happened kind of late in the cycle. And so election officials were not always as included as they should have been in developing the plan,” said Norden, of the Brennan Center for Justice. “My guess is that it’s going to be a little bit smoother this year, because everybody that’s involved in that process is going to be more aware from the start that election officials need to be included in the process to begin with.”

The election official who spoke to NPR on background said this time they made a conscious effort to engage the local grant applicants ahead of the deadline, but they weren’t sure that was happening in other states.

Multiple experts including Norden said the grant rollout pointed to a broader challenge for local election officials: They never have a clear sense of when or how much more funding is coming from the federal government, so it’s hard to plan around.

In the past six years, unrelated to the DHS grants, Congress has allocated more than $400 million some years and zero dollars others. In 2024, lawmakers settled on $55 million for elections — a fraction of what many election experts say is needed each year.

“If we could see a consistent number that election officials could rely on, that would make planning a lot easier. And frankly, it would mean that we wouldn’t be falling behind the way we are now when there are new challenges, whether it’s physical security or artificial intelligence that election officials have to address,” Norden said. “Hopefully this little bucket of money, this $30 million [of DHS grant money], will now be consistent. So election officials will know that it’s there. And again, while it’s small relatively … it’s definitely better than nothing.”

[ad_2]

Badejo Titilope

Good