ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

[ad_1]

When Ryan Millsap arrived in Atlanta from California a decade ago, the real estate investor set his sights on becoming a major player in Georgia’s booming film industry. In just a few years, he achieved that, opening a movie studio that attracted big-budget productions like “Venom,” Marvel’s alien villain, and “Lovecraft Country,” HBO’s fictional drama centered on the racial terror of Jim Crow America.

As he rose to prominence, Millsap cultivated important relationships with Black leaders and Jewish colleagues and won accolades for his commitment to diversity. But allegations brought by his former attorney present a starkly different picture. In private conversations, court documents allege, Millsap expressed racist and antisemitic views.

Various filings in an ongoing legal fight show Millsap, who is white, making derogatory comments regarding race and ethnicity, including complaints about “Fucking Black People” and “nasty Jews.”

“Ryan’s public persona is different from who he is,” John Da Grosa Smith, Millsap’s former attorney, alleges in one filing, adding: “Ryan works hard to mislead and hide the truth. And he is very good at it.”

Smith submitted troves of text messages between Millsap and his former girlfriend as evidence in two separate cases in Fulton County Superior Court. The messages, reviewed by ProPublica and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, represent a fraction of the evidence in a complex, yearslong dispute centered on compensation for the work Smith performed for Millsap.

In response to a request for an interview about the text messages and related cases, Millsap wrote that this “sounds like a strange situation,” asking “how this came up” and requesting to review the material. After ProPublica and the AJC provided the material cited in this story, he did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Many of the text messages filed with the court were sent in 2019, an important year for Millsap. He was planning an expansion of his Blackhall Studios that would nearly triple its soundstage space. Instead, Millsap ended up selling Blackhall, now called Shadowbox, for $120 million in 2021. The following year he announced plans to build a massive new complex in Newton County, about 40 miles east of Atlanta.

Smith started working for Millsap in August 2019, representing the film executive and his companies in a lawsuit brought by a business associate who claimed a stake in Blackhall. In May 2020, Smith became Blackhall Real Estate’s chief legal counsel.

Their relationship soured in early 2021. In the ensuing feud, Smith claimed that Millsap had promised him a third of his family company, as well as compensation for extra legal work — and, in a letter from his attorney, demanded that Millsap pay him $24 million within four business days: “We, however, have no interest in harming Mr. Millsap or disrupting his deal, his impending marriage, his future deals, or anything else.”

In the arbitration proceeding that followed, Millsap’s attorneys described the letter as “extortionate” and claimed that Smith was trying to “blow up” Millsap’s personal and business life and stall the sale of Blackhall Studios. _“_Smith breached the most sacred of bonds that exist between a lawyer and his or her clients: the duty of loyalty,” lawyers for Millsap later wrote.

In the same proceeding, Smith accused Millsap of firing him after he raised allegations of a hostile and discriminatory workplace, referencing Millsap’s text messages. Smith’s late father was Jewish.

In January 2023, an arbitrator sided with Millsap, ordering that Smith pay him and his companies $3.7 million for breach of contract and breach of fiduciary duty. She ruled that Smith’s conduct was “egregious and intended to inflict economic injury on his clients.”

Through his attorney, Smith declined to be interviewed. In response to a list of questions, he wrote, “This has been a tireless campaign of false narratives and retaliation against me for more than three years.” He claimed that his employment agreement with Millsap guaranteed him a cut of the profits he helped generate and that an expert estimated his share to be between $17 million and $39 million.

Even as Millsap won his legal fight with his former attorney, Smith has continued to press the court battle. In an April 2023 motion to vacate, Smith called the arbitration process a “sham” and the award a “fraud,” and he is now appealing a judge’s decision to uphold the award. In January, a lawyer for Smith filed hundreds of pages of Millsap’s texts in a separate legal dispute in which Millsap is not a party.

In a city with dominant Black representation and a significant Jewish population, maintaining a positive relationship with these communities — or at least the appearance of one — is essential to doing business.

“Mr. Millsap knows,” Smith alleged in one filing, “these text messages are perilous for him.”

On a Thursday night in January 2019, Millsap stood near the pulpit at Welcome Friend Baptist, a Black church 10 miles from downtown Atlanta in DeKalb County, near where he was planning the expansion of his movie studio.

Securing support from the community would be key in convincing the county commission to approve a land-swap deal that would be necessary for the expansion. Several commissioners saw the project, including Millsap’s promise to create thousands of jobs, as a way to revitalize the area.

Dozens of longtime residents, most of them Black, sat in the sanctuary’s colorful upholstered chairs. The attendees received information sheets on Blackhall’s plans, which cited $3.8 million in public improvements, including the creation of a new public park. They asked about internship opportunities for their children and restaurants Millsap might help bring.

Millsap raised the possibility of a restaurant, one he said could offer healthy meals. Several older Black women in the church nodded in agreement and one clapped, Millsap’s pitch seemingly helping him appeal to those whose buy-in he needed.

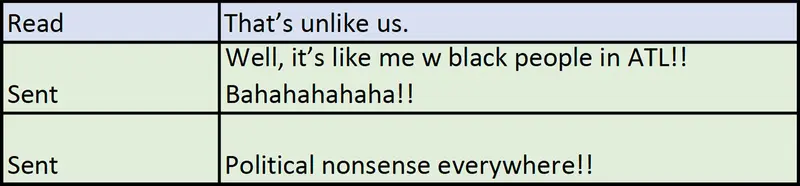

Two months later, Millsap sent his then-girlfriend a text that Smith’s lawyers later alleged shows he “laments his political work with African Americans and his distaste for having to do it.”

In the text exchange, which was filed in court, Millsap wrote: “Well, it’s like me w black people in ATL!! Bahahahahaha!! Political nonsense everywhere!! … I’m so ready to be finished w that.”

Credit:

Screenshot from a court exhibit filed by John Da Grosa Smith’s attorney in January

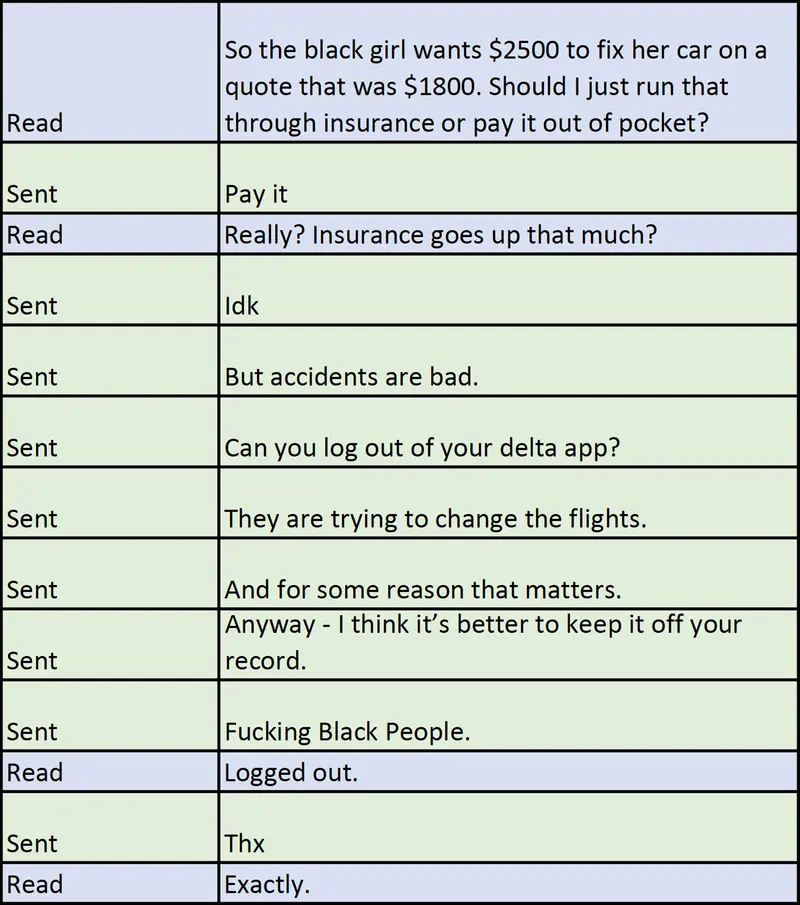

In another text filed in court, Millsap’s girlfriend alluded to the damage she’d caused another vehicle in a car accident: “So the black girl wants $2500 to fix her car on a quote that was $1800.” He responded that she should pay the woman rather than filing an insurance claim, adding, “Fucking Black People.”

Credit:

Screenshot from a court exhibit filed by John Da Grosa Smith’s attorney in January

Court records and Millsap’s own testimony show that his girlfriend at the time, Christy Hockmeyer, was an investor in his real estate company, and their text messages show she played an active role in his business dealings. In a filing that claims the company had a “hostile and discriminatory work environment,” Smith alleged that Blackhall Real Estate “through its CEO, Ryan Millsap, and one of its influential investors, Christy Hockmeyer, disfavors African- Americans and Jews.”

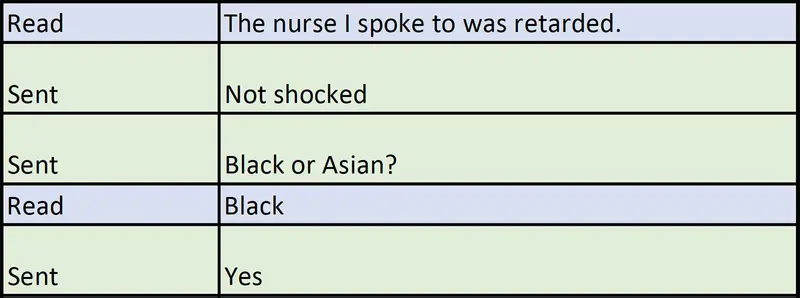

When Hockmeyer texted Millsap after a doctor’s visit, complaining that a nurse was “retarded,” Millsap responded: “Not shocked. Black or Asian?” Hockmeyer wrote back: “Black.” Millsap replied, “Yes.”

Credit:

Screenshot from a court exhibit filed by John Da Grosa Smith’s attorney in January

In other exchanges filed with the court, Hockmeyer complained to Millsap, “My uber driver smells like a black person. Yuck!” He echoed her sentiment, writing back, “Yuck!” While on a flight, Hockmeyer wrote to Millsap that a “large smelly black man is seated next to me.” Millsap wrote back, “Yucko!!”

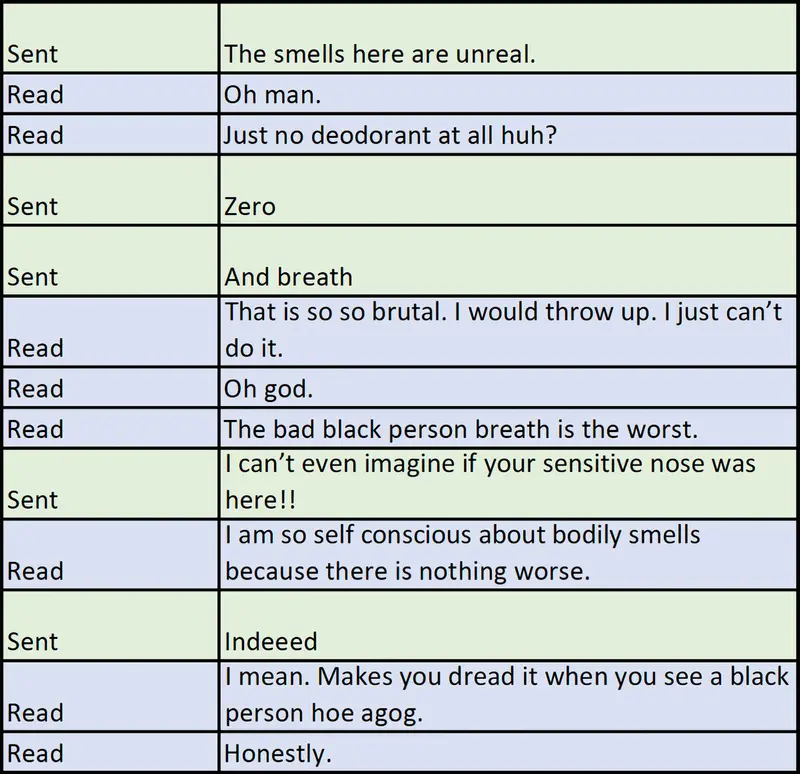

And while passing through an airport in France, Millsap texted Hockmeyer, “The smells here are unreal” and “I can’t even imagine if your sensitive nose was here!!”

Hockmeyer responded, “I am so self conscious about bodily smells because there is nothing worse. I mean. Makes you dread it when you see a black person.”

Credit:

Screenshot from a court exhibit filed by John Da Grosa Smith’s attorney in January

Smith alleged that the conversations between Millsap and Hockmeyer reveal how they think about people with whom they conduct business. “The insidious belief that ‘black’ people are beneath them and not worthy of being hired is a theme that persists in their private writings to one another,” Smith said in the filing.

At a time in 2019 when Millsap was looking to hire an executive with a track record in the Atlanta film industry, Hockmeyer texted him that he might consider bringing on someone from Tyler Perry Studios, a 12-stage southwest Atlanta lot named after its founder, one of the highest-profile Black film producers in the country. “And taking someone from Tyler Perry would be fine too,” she wrote in a text exchange filed with the court. “As long as they are white.”

She also offered another name for Millsap to consider, adding: “He’s even a Jew. That’s good for this role.” Millsap responded, “Teeny tiniest Jew.”

On another occasion, Hockmeyer “opined that Anglo-Americans do not do business with Jewish people,” Smith alleged in a court filing, referencing a text message exchange in which she wrote to Millsap: “You know why wasps won’t do deals with Jews? Because they know that Jews have a different play book and they might get screwed.” Smith also claimed in a court filing that Millsap described to Hockmeyer “a terrible meeting with one of the most nasty Jews I’ve ever encountered.”

In an email to ProPublica and the AJC, Hockmeyer wrote: “I severed all personal and professional ties with Mr. Millsap years ago because our values, ethics, and beliefs did not align. As a passive investor in Blackhall, I was not involved in the day-to-day operations of the company, nor have I been party to any of the lawsuits involving Blackhall. I consistently encouraged Mr. Millsap to treat his investors and community supporters with fairness and respect.”

In a subsequent email, she apologized for the texts between her and Millsap. “There were times when I may have become angry or emotional and tacitly acknowledged statements he made or said things that do not reflect my values or beliefs, and I deeply regret that,” she wrote, adding: “I made comments and used language that was inappropriate. I referred to people in ways I shouldn’t have. I’m sincerely sorry for what I said. Those comments do not reflect who I am and I disavow racism and antisemitism as a whole.”

Smith claimed in a court filing that Millsap regularly expressed disrespect toward Jewish people, describing three of his Jewish colleagues and investors as “the Jew crew,” calling one of them “a greedy Israelite” and saying another had “Jew jitsued” him. Millsap concluded, according to Smith, that “no friendship comes before money in that tribe.”

During the arbitration, Millsap testified in August 2022 that his remarks about people of the Jewish faith constituted “locker room talk.”

In December 2019, Millsap received several warnings from Hockmeyer, according to arbitration records that highlight excerpts from some of her text messages. (Other exhibits in the case show the couple’s relationship had become strained around that time.)

“Ryan you have to understand why people are over your bulls**t,” she wrote that month, according to the records. “They feel lied to taken advantage of and stolen from.”

The following month, she wrote: “Wow. You are going to get lit the f**k up. Holy s**t you are such a bad person. You are a f**king crook!”

During the arbitration hearing, one of Smith’s attorneys asked Millsap about some of Hockmeyer’s December 2019 warnings. He responded, “These are the text messages of a very angry ex-girlfriend.”

As Smith began taking on more responsibility for his client in 2020, Millsap continued to connect with Black influencers and cement himself as a cultural force in Atlanta.

In December of that year, Millsap was a guest on an episode of actor and rapper T.I.’s “Expeditiously” podcast. After discussing the differences between the Atlanta and Los Angeles entertainment markets, Millsap praised what he called “a very robust, Black creative vortex” in Atlanta. And he went on to offer more praise. “There seems like a particular magic in Atlanta about being Black.”

He also talked about his studio expansion plans amid the land-swap deal in a majority-Black DeKalb County neighborhood, telling T.I., “It’s been a fascinating study in race actually.”

Millsap went on to explain how his business interests aligned with the desires of residents. “What pushed this through was Black commissioners supporting their Black residents who wanted to see this happen, right?” he said. “They’re fighting against one white commissioner and a lot of her white constituents who took it upon themselves to be against this when they’re not even the residents who live nearby.”

One evening in August 2021, Millsap stepped onto the stage at the Coca-Cola Roxy theater in Cobb County. He and a dozen other people had been named the year’s Most Admired CEOs, an honor awarded by the Atlanta Business Chronicle. The CEO’s were recognized for, among other things, their “commitment to diversity in the workplace.”

As the dispute between Smith and Millsap unfolded, Millsap expanded his business interests to Newton County, where he purchased a $14 million, 1,500-acre lot in 2022. He said at the time that his vision is to make Georgia a “King Kong of entertainment” by building a production complex on the site and launching a streaming service that, in his words, would be “something on the scale of Netflix.” He later invested in a vodka brand with the aim, he said, of it becoming “quintessentially” Georgia, “like Coca-Cola and Delta.”

Earlier this year, Millsap sat down in his stately home office, decorated with Atlanta-centric trinkets like a model Delta plane, to record an episode of his “Blackhall Podcast with Ryan Millsap.” T.I. has been a guest, as have Isaac Hayes III, son of the iconic soul singer Isaac Hayes and a social media startup founder, and Speech, the frontman for the Atlanta-based, Grammy-winning musical act Arrested Development.

On this day, Millsap talked about race and culture, pointing out that one of his best friends is a “Persian Jew in LA”

Millsap noted that his understanding of “Black and white” was formed on the West Coast, where he had “a lot of Black friends” — “very Caucasian Black people” who had adopted white cultural norms.

“I grew up thinking like I had no racial prejudice of any kind,” Millsap said. “I thought we were beyond all that stuff.”

Rosie Manins of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution contributed reporting.

[ad_2]

Zita boo

Interesting

Adelagun Adebisi

Good

Ahmed Ibrahim

Na them sabi jare