ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

[ad_1]

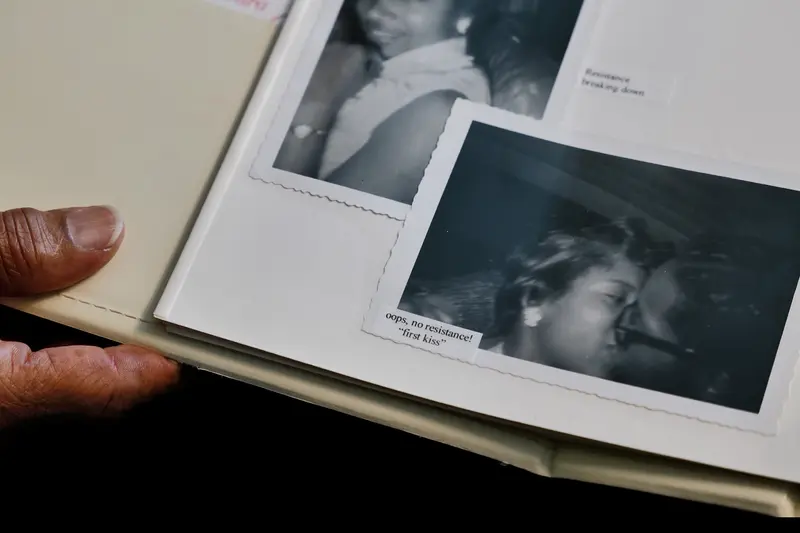

James and Barbara Johnson flip through a book of their memories. They arrive at a photograph Mr. Johnson snapped as a surprise: a photograph of the long-married couple’s first kiss.

Even after all this time, Barbara Johnson quietly says to herself, “I don’t know how he did that.”

“Me neither,” James Johnson says with a laugh.

Credit:

Christopher Tyree/VCIJ at WHRO. Original photograph by James Johnson.

The Johnsons are the center of a short documentary ProPublica released last year. The documentary, “Uprooted,” is part of an investigative project reported by Brandi Kellam and Louis Hansen, both of the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO, in partnership with ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network and co-published by the Chronicle for Higher Education and Essence. The investigation examines a Black community’s decadeslong battle to hold on to its land as city officials wielded eminent domain to establish and expand Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia.

Now in his 80s, James Johnson has spent decades chronicling through photographs the life of a neighborhood that for the past several decades he’s watched disappear. The Johnsons live in one of five remaining homes of what was once a flourishing middle-class Black community, with roots that extend to the late 1800s. James Johnson’s grandfather, in 1907, purchased slightly more than 30 acres of land in what’s called the Shoe Lane area.

Credit:

Courtesy of James Johnson

Eventually, the Shoe Lane community expanded from mostly a community of farmers and laborers to a growing middle-class community including dentists, teachers and a NASA engineer in 1960. This was during a time when racial segregation was a legal pillar of American society, and all-white communities, including the then-all-white Christopher Newport University, enjoyed systematized benefits not afforded to Black people.

Credit:

Courtesy of James Johnson

Credit:

Courtesy of James Johnson

As Brandi reported, the 110-acre Shoe Lane area was adjacent to one of the city of Newport News’ most affluent white neighborhoods. So, when the Johnsons made it known they intended to subdivide more of their 30 acres to help provide Black families with opportunities for homeownership, the all-white City Council perceived it as a threat. Like many localities in midcentury America, the Newport News City Council had weaponized urban renewal against Black people to maintain racial segregation and the illusion of white superiority.

Brandi found that in 1961, the city used eminent domain to “seize the core of the Shoe Lane area, including the Johnsons’ farmland, for a new public two-year college — a branch of the Colleges of William and Mary system.” That college eventually became Christopher Newport University.

Credit:

Courtesy of James Johnson

At the time, the university and City Council all but ignored the community’s protests. Instead, the narrative conveyed by the white newspaper was that the Black people of Shoe Lane were against the university because they were anti-education.

For a story that for so long had been told wrong, Brandi saw an opportunity for her reporting to get the story right.

As bulldozers and trucks filed into Shoe Lane over various waves of university expansion, James Johnson turned to his camera to preserve what he could. His photographs became evidence Brandi relied on in her reporting. While investigative reporters often use Freedom of Information Act requests and government data to document the past, Johnson’s personal archive told the story of what happened to Shoe Lane better than the official records.

Credit:

Courtesy of James Johnson

Credit:

Courtesy of James Johnson

Credit:

Courtesy of James Johnson

“I just started knocking on doors,” Brandi told me of how her reporting began two years ago. “The person who opened the door for me was Mrs. Johnson.”

When Brandi eventually met James Johnson, she sat with him for hours. She said she let him teach her what happened; she absorbed the history like a sponge.

“He just started opening up these notebooks,” recalled Brandi. “I almost fainted.”

He had kept the original deeds to the land his grandfather bought. He printed out parcel data that was no longer publicly available. He had photographed the front of dozens of homes that no longer existed, writing on sticky notes captions that could only hint at the emotional weight they carried to a community as it was systematically dismantled.

“He collected this not because he was looking for someone to tell the story,” said Brandi. “He did it because he was deeply hurt by what happened to his community.”

What Johnson’s archive documented was, in one light, a story of loss. But, said Brandi, his documenting was also an act of love.

Credit:

Courtesy of James Johnson

His photographs of his own family and of the community depict lifetimes of what the people of Shoe Lane had earned and experienced for themselves. Today, the Johnsons’ home — the one they built with their own hands — is only one of five remaining. The university’s updated site plan calls for acquiring the last houses in the neighborhood by 2030, Brandi reported.

Credit:

Christopher Tyree/VCIJ at WHRO

But, for the first time, the university is publicly reckoning with the damage it’s caused to the Shoe Lane area. In January, the university announced its launch of a joint task force with the city of Newport News to reexamine decades of records regarding the neighborhood’s destruction. It may also recommend possible redress for those uprooted families. That reckoning is because of Brandi’s reporting and the accountability lens she’s brought to the story of Shoe Lane. But, Brandi said, her work is building on James Johnson’s project of making sure people don’t forget about Shoe Lane.

The investigation has also prompted attention from Virginia lawmakers, who’ve approved a commission to examine universities’ displacement of Black communities. That commission would consider compensation for dislodged property owners and their descendants.

[ad_2]