[ad_1]

Sometimes, when I watch a short film, particularly a documentary, I come away feeling that it could have gone on another thirty minutes or so, and I still would’ve been hooked. Lydia Cornett’s film “Fleshwork” is roughly six and a half minutes, and when it ended, I initially felt it was too short. For some reason, despite its subject matter, I wanted more. Often, in a case like this, it’s a good idea to watch it again and see it as a perfectly self-contained piece that accomplishes what it needs to without having to tip any scales or go the extra mile to provoke the viewer for the sake of doing so. Brevity is the soul of wit, of course, and Cornett’s concise and hypnotic film will get a conversation going in your head when it’s over, which is more than many features can do.

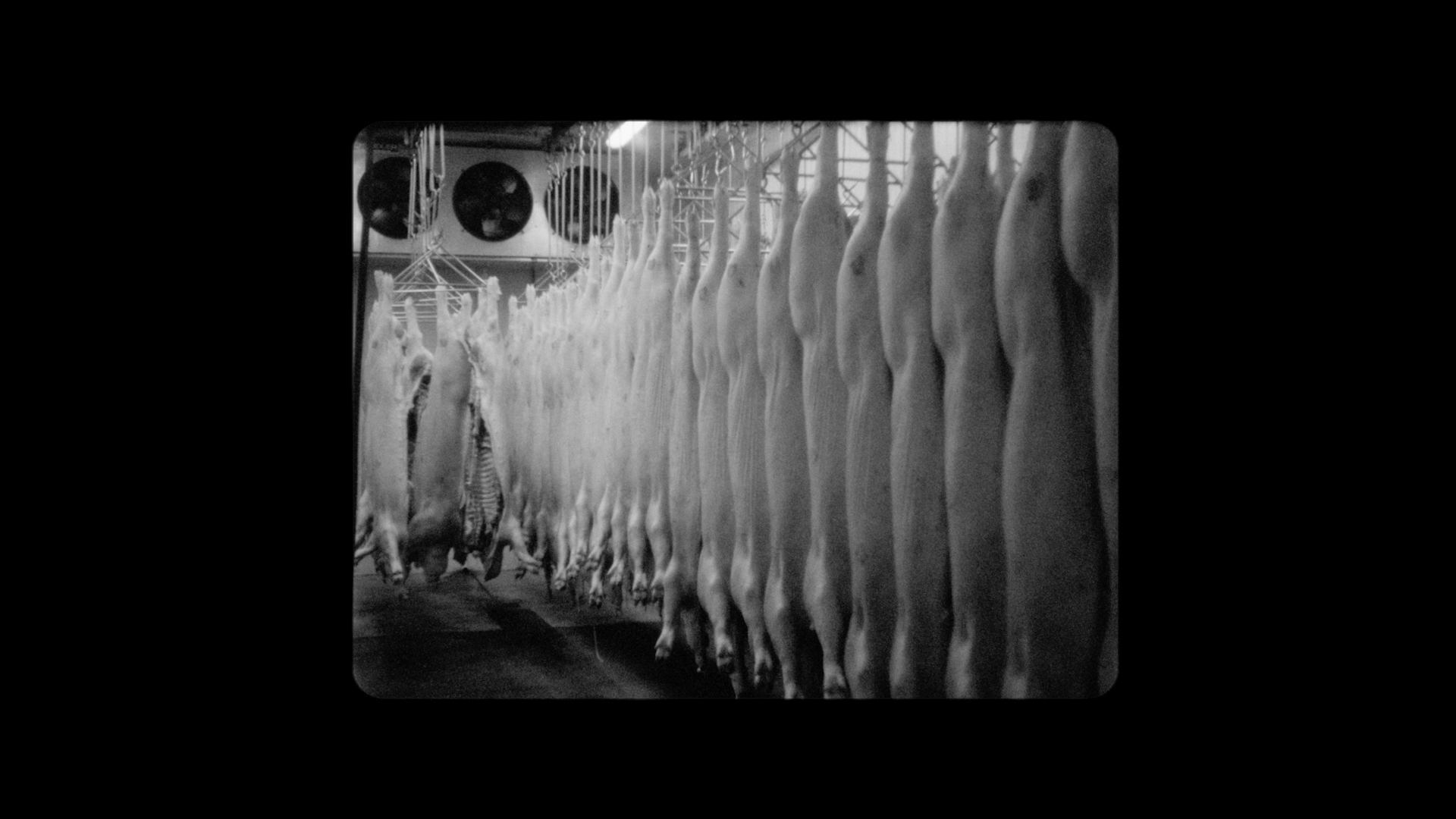

The film concerns people who work in “meat processing.” That’s in quotes because that’s what one of the workers prefers to call himself. A “butcher” is too off-putting for most people. A “meat processor” is easier to, well, process. The film depicts this process (mainly pig carcasses) as we hear men off-screen talk about the nature of the job, what it means to them, and how, in a strange way, to carve and shape a piece of meat is tantamount to artistic expression. It has to look great to be sold, so it’s like creating a sculpture.

Cornett keeps the faces of these people off-camera and sticks to beautifully photographed black-and-white shots of meat cutting, meathooks, disposal, carving, and shipping. It’s not pleasant. We are watching the sausage get made in a manner of speaking, which will likely put off many viewers. It never feels like Cornett is trying to provoke the viewer into considering (or reconsidering) anyone’s eating habits. She seems genuinely curious about this line of work and what people get out of it, which also makes the viewer curious.

The matter-of-fact approach works well here. There are more than enough cautionary films about meat-eating out there in the world, and “Fleshwork” works not as a counterpoint to them but as an exploration into a corner of the food market most people would never consider for gainful employment. Somebody has to do this job and it just so happens some people like doing it. If you’re a meat-eater (as I am), there is some comfort in knowing that while setting your table.

Q&A with director Lydia Cornett

How did this come about?

I spent two years of the pandemic living in Columbus, Ohio. While most public spaces and businesses were closed or in the process of reopening, I explored the central Ohio region on long drives around the state and eventually came across Heffelfinger’s Meat Shop in Jeromesville. I’ve always been interested in the way humans relate to animals meant for consumption or sale — my previous film, “Bug Farm,” for example, is a portrait of workers at an insect farm in central Florida. When I began filming at the butcher shop, I was struck by how the meat processors I spoke to expressed the nature of their work: as an art form, a contested and sensitive trade, and a daily exertion that made them consider their own bodies in relation to those they were disassembling.

Was there apprehension among the workers about going on-camera for their interviews, or was it the idea to always keep them off-camera?

I shot the film on a Bolex, a hand-wound 16mm film camera that isn’t designed to record synced sound. So, going into the project, I knew I would be working with sound and image separately, and I think that allowed me to be specific about what I wanted each of those mediums to achieve. I also recorded the audio interviews with the meat processors while they were working, which I think allowed for a natural flow and directness that a camera or bigger crew might have disrupted.

Did making the movie change your own point of view on meat or meat eating in any way?

Making the film definitely made me think about how disparate the experience of buying meat as a consumer is from the process of meat production. However, I was most interested in understanding

the complexities of this labor that is so often hidden from the public eye. I was fascinated by the way the workers could look at these animals and notice markers of aging that they could feel in themselves. Rarely is scientific knowledge recognized as a skill inherent to working-class communities and trade jobs, and it was important to me that the film portrays the anatomical expertise required of this profession.

What was the editing process like? Was there anything cut from the final film that would have changed its character or tone?

For a while, I felt very stuck in the film’s edit, but things started coming together as I simultaneously started working on an original musical score. I assembled snippets of field audio and improvisations on my violin, and these soundscapes helped me form the film’s thematic chapters. While the first half of “Fleshwork” documents the activity in the butcher shop with a mix of wide and close static observational shots, the ending musical section makes use of tight framings of movement to create a choreographic sequence. To me, the music brings my perspective to this space that might otherwise feel very masculine and inaccessible, making me more of a converser rather than a voyeur.

What’s next for you?

I’m currently in post-production on a short documentary about gender fluidity in opera that I’m co-directing with filmmaker Brit Fryer. I also just moved to Budapest for a Fulbright, where I’m researching and developing some new projects.

[ad_2]