[ad_1]

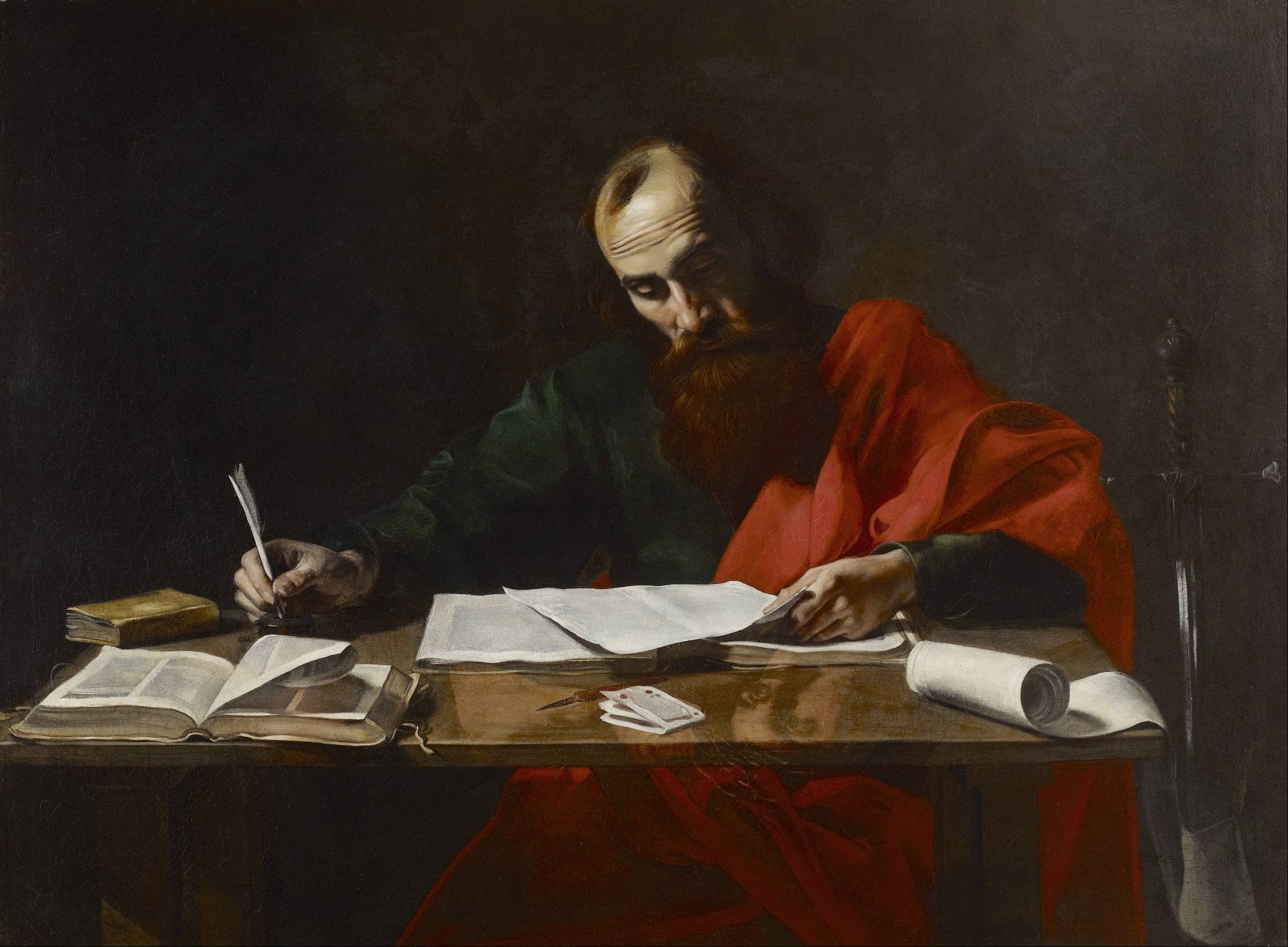

Art and literature work in tandem to fortify myths of single-handed brilliance, creating a reverence for the proverbial “solitary genius.” Romantic depictions of the ancient author toiling away at his desk or the medieval bishop writing letters while alone in his study reinforce and reinscribe the aesthetics of authorship as a lonely, inspired endeavor. In truth, these are far from authentic depictions of true authorship. But while the collaborative nature of many types of visual art within Renaissance and modern artist workshops is now well-documented, the reverence for books, scripture, and other texts allegedly written by a single Christian author continues unabated — until now, with academics further investigating a crucial question: How did ancient authors actually compose their works?

New scholarship is beginning to interrogate how we envision ancient writers like those who penned the gospels, and to provide visibility for the enslaved labor behind everything from the writing of the New Testament to the copying of early Christian writings. The role of enslaved people in the proliferation of Christianity and the papacy reveals the ways in which art has concealed their contributions.

In ancient Egypt and early Imperial China, scribes were of high status and revered by elites and monarchs. But in many Greek and Roman cities, villas, libraries, churches, and even monasteries, ancient texts were often written down and copied through the use of enslaved labor. Enslaved persons came from all over the Mediterranean in Greek and Roman society. They were often taken as war captives or born into slavery within their households. Some were then trained as scribes called by a variety of names such as scriba or amanuensis. Enslaved writers like Aesop, allegedly penning his fables in the 6th century BCE, wrote down their own stories. Far more were forced to write down the words of others by serving as secretaries, stenographers, letter writers, contract notaries, and collaborators for their enslavers. There was Cicero’s famed dictation to his enslaved secretary Tiro, whom he later freed; or Epaphroditus, the formerly enslaved writing attendant to the emperor Nero. However, the use of enslaved labor was not limited to works by classical authors. There is also evidence that enslaved people contributed to the work of early Christians, as well.

Traditional scholarship views the New Testament as authored individually by a small group of men: Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, James, Peter, and Paul. But a new book by Biblical scholar Candida Moss, God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible, questions the production of this and other Christian texts. Moss points to key indicators that enslaved workers were relied upon as secretaries, messengers, editors, and even authors of pivotal pieces of scripture. Perhaps the most telling evidence for enslaved ghostwriters resides in the letters of the Apostle Paul.

While the Apostle Paul and his entourage were in the Greek city of Corinth around the year 56 CE, he sent out the famed letter to the Romans. Except, a telling detail notes that it was actually a man named Tertius, meaning “Third” in Latin and a name common for enslaved persons, who wrote the letter down in Greek, rather than Paul himself. From medieval manuscripts to multiple paintings by Rembrandt, myriad illustrations of Paul writing would follow in the centuries thereafter. As Moss points out, Tertius is absent from all but a precious few of these depictions. A rare etching by the 17th-century Dutch printer Jan Luyken renders Paul dictating to the likely enslaved Tertius, but far more common are depictions of Paul and other Christian writers toiling alone, perhaps with the help of the holy spirit or the hand of God for inspiration.

Medieval and early modern art depicting early Christianity only rarely provides depictions of enslaved persons used or enslaved by the church. But far from rejecting slavery, servitude was a part of Christianity’s foundations. As early Christian slavery expert Jennifer Glancy wrote in her book Slavery in Early Christianity, “Christianity was born and grew up in a world in which slaveholders and slaves were part of the everyday landscape.” Enslaved people were more than landscape features: As Moss, Glancy, and other scholars explain in recently published writings, they were also treated as chattel to be bought and sold by Christians.

Moss underscores this point by looking to ancient texts from outside the New Testament canon, known as apocrypha. A popular 3rd-century text entitled the Acts of Thomas highlights the fact Jesus had few qualms with selling individuals into slavery if need be. When Jesus tells Thomas to evangelize on a mission to India, the apostle refuses. In response, Jesus sells the apostle as an enslaved carpenter to an Indian merchant named Abbanes, who worked for the Indian king Gundaphorus, also known as Gondopherrnes I. In many ways, the story grafts onto Thomas the many attributes of better-known enslaved message carriers used within the Roman Empire called tabellarii, Latin for “those who carry tablets.”

Looking further into the history of Christianity and clerics, strong evidence suggests that bishops and the Pope himself continued to buy, sell, and use enslaved persons within their households. The early 4th-century bishop Eusebius noted in his history of the church that the prolific early Christian writer Origen of Alexandria (184–253 CE), alleged author of over 2,000 treatises, also used “seven shorthand writers who relieved each other at fixed times, and as many copyists, as well as girls trained for beautiful writing.” As historian of early Christianity Kim Haines-Eitzen writes in her “Female Scribes in Roman Antiquity and Early Christianity,” many if not most of the male and female Roman scribes at this time were enslaved or manumitted.

Over the course of centuries, late Roman and medieval churches enslaved thousands of people. Scholar Mary E. Sommar examines the early history of ecclesiastical enslaved people in her 2020 book, The Slaves of the Churches: A History. Perhaps one of the most celebrated of these early bishops of Rome was Pope Gregory I, who served from 590 to 604 CE. He was a prolific writer, particularly of letters, and visual artists have often depicted him writing. As Sommar discusses, Gregory’s letters contain instructions for a priest named Candidus to purchase enslaved young Angles to be used by the church. In one study, ancient historian Adam Serfass reconstructs how Gregory gave enslaved people to his friends and ordered them bought at auction and even tortured. The famed late-10th-century ivory of Gregory from Lorraine, now in Vienna at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, depicts him writing while hunched over his desk. Monastic scribes write below him, but Gregory appears solo, save for the dove of the holy spirit whispering to him. If he did use enslaved secretaries, you wouldn’t know it from the art.

From antiquity well into the mid-19th century, certain clerics and monastic orders in Europe continued to enslave people. Some of these enslaved individuals worked in agricultural jobs while others did menial chores. And even if they were not always the ones writing down texts in the scriptorium, churches used their labor to provide free time to clerics and monks to do their own writing and research. As these new studies of antiquity illuminate, Christianity was greatly influenced by enslaved persons, even if they are rarely depicted or cited by name.

The worlds of authorship, artistry, and slavery are not — and never have been — mutually exclusive. While some museums have begun to address slavery and its innumerable connections to the art world, there is much left to do. In 2023, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York put on the first major exhibition celebrating the Afro-Hispanic painter Juan de Pareja (c. 1608–70). De Pareja is the subject of artist Diego Velázquez’s famed portrait, but was also enslaved in his workshop. Still other works may need similar consideration.

The Metropolitan Museum of Aart also holds a 15th-century altar depicting Saints Peter, Paul, and John the Baptist with their books and scrolls as representatives of early Christian literary culture. Italian records show that Renaissance sculptor Gerardo di Mainardo, who created the piece, enslaved a Venetian stone carver named Martino. He worked in di Mainardo’s workshop and had a hand in many of the sculptor’s famed stone carvings. As the buried labor of everyone from Tertius to Martino demonstrates, authorship and artistry are rarely solo endeavors of solitary genius. Part of the brilliance of contemporary artists like Titus Kaphar and Ken Gonzales-Day is that they remind us of the potential to address slavery head-on through both the pen and the paintbrush — and to dispel the pernicious myths of the lone genius once and for all.

[ad_2]