As our climate changes, we fear that warmer temperatures and drier conditions could make life hard for us. In most locations, it’s a future concern that feels uncomfortably near, but for some locations, it’s already very real. Take the Sahara desert, for example, and the degraded landscapes to the south in the Sahel. These arid regions are so dry that they struggle to support life at all, and temperatures there are rising faster than almost anywhere else on the planet.

In the face of this escalating threat, one of the most visionary initiatives underway is the Great Green Wall of Africa. It’s a mega-sized project that aims to restore life to barren terrain.

A Living Wall

Launched in 2007 by the African Union, the Great Green Wall was originally an attempt to halt the desert in its tracks. The Sahara Desert has long been expanding, and the Sahel region has been losing the battle against desertification. The Green Wall hopes to put a stop to this, while also improving food security in the area.

The concept of the wall is simple. The idea is to take degraded land and restore it to life, creating a green band across the breadth of Africa which would resist the spread of desertification to the south. Intended to span the continent from Senegal in the west to Djibouti in the east, it was originally intended to be 15 kilometers wide and a full 7,775 kilometers long. The hope was to complete the wall by 2030.

The Great Green Wall concept moved past initial ideas around simply planting a literal wall of trees. It eventually morphed into a broader project to create a “mosaic” of green and productive landscapes that can support local communities in the region.

Reforestation is at the heart of the Great Green Wall. Millions of trees have been planted, with species chosen carefully to maximise success. Trees like Acacia, Baobab, and Moringa are commonly planted not only for their resilience in arid environments but also for their economic benefits. Acacia trees, for instance, produce gum arabic—a valuable ingredient in the food and pharmaceutical industries—while Moringa trees are celebrated for their nutritious leaves.

Choosing plants with economic value has a very important side effect that sustains the project. If random trees of little value were planted solely as an environmental measure, they probably wouldn’t last long. They could be harvested by the local community for firewood in short order, completely negating all the hard work done to plant them. Instead, by choosing species that have ongoing productive value, it gives the local community a reason to maintain and support the plants.

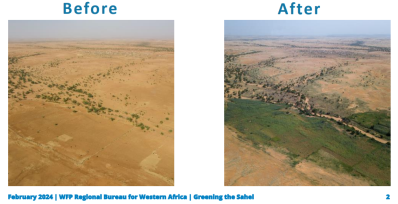

Special earthworks are also aiding in the fight to repair barren lands. In places like Mauritania, communities have been digging half-moon divots into the ground. Water can easily run off or flow away on hard, compacted dirt. However, the half-moon structures trap water in the divots, and the raised border forms a protective barrier. These divots can then be used to plant various species where they will be sustained by the captured water. Do this enough times over a barren landscape, and with a little rain, formerly dead land can be brought back to life. It’s a traditional technique that is both cheap and effective at turning brown lands green again.

Progress

The initiative plans to restore 100 million hectares of currently degraded land, while also sequestering 250 million tons of carbon to help fight against climate change. Progress has been sizable, but at the same time, limited. As of mid-2023, the project had restored approximately 18 million hectares of formerly degraded land. That’s a lot of land by any measure. And yet, it’s less than a fifth of the total that the project hoped to achieve. The project has been frustrated by funding issues, delays, and the degraded security situation in some of the areas involved. Put together, this all bodes poorly for the project’s chances of reaching its goal by 2030, given 17 years have passed and we draw ever closer to 2030.

While the project may not have met its loftiest goals, that’s not to say it has all been in vain. The Great Green Wall need not be seen as an all or nothing proposition. Those 18 million hectares that have been reclaimed are not nothing, and one imagines the communities in these areas are enjoying the boons of their newly improved land.

In the driest parts of the world, good land can be hard to come by. While the Great Green Wall may not span the African continent yet, it’s still having an effect. It’s showing communities that with the right techniques, it’s possible to bring some barren zones from the brink, turning hem back into useful productive land. That, at least, is a good legacy, and if the projects full goals can be realized? All the better.