[ad_1]

On Monday, the Supreme Court decided not to decide two big cases from Texas and Florida about social media laws. Instead, it remanded the cases back to lower courts, chastising the white-shoe firms representing Big Tech plaintiffs for bringing the cases at a premature stage. Netchoice, the Facebook and Google trade group, had brought the cases as “facial challenges,” asking the court to find that there were substantially more unconstitutional applications of the laws than constitutional ones. A facial challenge win would not just have blocked these laws but would have halted future tech regulation.

The court’s ruling in Moody v. Netchoice was a major surprise, and a big loss for Meta, Google, and TikTok. Most observers thought the laws would be struck down, granting the tech giants their own form of immunity—from legislation. Their victory was so much a foregone conclusion that some news outlets had prewritten wins for Netchoice. “Supreme Court Strikes Down Anti-Censorship Social Media Laws In Win For Tech Platforms”, the initial HuffPost headline read, which is exactly what the court did not do. (It was quickly edited for the more accurate “Supreme Court Bounces Back Question On Social Media Moderation.”) I heard The Washington Post had a similar prewritten “strikes down” headline.

Because it is a remand, the words in the opinions are all dicta (comments or observations, not legally binding). All that really matters is that the cases have been sent back. That’s good news for the dozens of child-protective social media laws recently passed, for AI regulation, and for other consumer protection laws that touch on the tech platforms’ business practices.

However, the opinions within the remand are also important as signals. While they do sound corporate-friendly, they also indicate genuine openness to a wide array of social media regulation, depending on the motive behind the legislation, the nature of the state interest, and the kind of regulation.

Justice Kagan wrote the majority opinion, joined by Kavanaugh, Roberts, Barrett, Sotomayor, and Jackson. Kagan is breezily corporate-friendly, relying heavily on a triad of cases with very different fact patterns in which the First Amendment was used to forbid state regulation. She argues that social media regulation is not different in kind from newspaper regulation, which is mostly barred by the First Amendment. Kagan then applied her broad logic to the curated feeds of Facebook and YouTube, essentially concluding that at least some aspects of the state laws were unconstitutional.

But what might look like a wall of corporate speech maximalism is actually full of uncertainties and signs that many regulations will be upheld.

Current Issue

First, Kagan seemed most affronted by the fact that the laws were motivated by a particular set of viewpoints, and were designed to suppress other viewpoints. She said the Texas law would likely not pass constitutional muster because it was “intended to suppress” speech that it didn’t like. That “intent to suppress” simply isn’t the purpose for many social media regulations, like consumer protection laws prohibiting particular social media design features. Second, Kagan approvingly cited Turner II, which upheld a federal law requiring cable operators to carry local stations, because of the strength of the state interest in that case. Clearly, a different state interest could make a difference; not all regulations are doomed. Third, she clearly signaled that sorting content based on “a user’s expressed interests and past activities” might be of different First Amendment value than platform-curation of content moderation. She wrote “we do not deal here with feeds whose algorithms respond solely to how algorithms act online.” By specifically naming algorithmic feeds, she indicates that laws regulating them could pass constitutional muster.

But perhaps the biggest revelation in the Netchoice cases is not Kagan but that Justices Amy Barrett and Kentanji Brown Jackson are going to be the all-powerful swing justices on tech regulation. Kagan needed either Barrett or Jackson for the majority; in the end, both concurred separately, and both signaled a far more sympathetic approach to tech regulation than Kagan’s own. They will hold the key to any future decision, and therefore their views—not Kagan’s—are the most important to understand.

Jackson, who was skeptical about the Netchoice overreach at oral argument, refused to engage in the substance at all, showing a graceful resistance to being dragged into theoretical fights. While Jackson concurred with some of Kagan’s opinion, she pointedly did not concur with Kagan’s efforts to analyze the constitutionality of the laws as applied to the Facebook feeds.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Barrett’s concurrence is more revealing. While she accepted Kagan’s logic at the most abstract level, she used her concurrence to note that new technologies are not the same as old ones. She even indicated that not all algorithmically determined speech is necessarily expressive speech, and certainly should not be treated the same. “The way platforms use this sort of technology might have constitutional significance.” Barrett’s concurrence wisely avoids conclusions, instead consisting of very pointed questions. She asks:

What if a platform’s algorithm just presents automatically to each user whatever the algorithm thinks the user will like?

What about AI, which is rapidly evolving?

What if a platform’s owners hand the reins to an AI tool and ask it simply to remove “hateful” content?

If the AI relies on large language models to determine what is “hateful”… has a human being with First Amendment rights made an inherently expressive “choice…not to propound a particular point of view”?

All of these questions point to an alert mind, ready to recognize the unique features of today’s technology, and not just shoehorn in 1970s newspaper precedent.

This is very good news for the constitutional status of child protection social media laws grounded in consumer protection principles. The recent “Stop Addictive Feeds Act”—passed in New York with overwhelming bipartisan support—prohibits algorithms from using personal data and inferences about individual children to serve them feeds. It does not address viewpoint or content at all; it merely bans platforms from doing precisely what Justice Barrett talked about: targeting feeds.

Barrett’s series of questions certainly suggest that if she’s the swing vote in analyzing whether a ban on addictive algorithm-driven feeds is constitutional, she’d lean towards affirming it, and be less sympathetic to the notion that Big Tech platforms have a First Amendment right to have AI automatically addict our children.

In other words, the Netchoice opinion is not just a signal to federal courts to slow down and analyze each function, law, and purpose in a fact-specific way. It’s also a signal to state lawmakers that there is room to breathe, innovate, and pass consumer protection laws and journalism protection laws—so long as they are not aimed at excluding specific viewpoints.

The story of the First Amendment in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has been a story of expansion. Designed to protect dissenters and newspapers, the First Amendment has become the favorite tool of multinational corporations to strike down democratically passed laws. “Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press” has become “Congress may not pass campaign finance laws (Citizens United, 2010; McCutcheon, 2014) or ban the sale of personal data to Big Pharma companies (Sorrell, 2011).”

Ad Policy

Big Tech companies have been especially eager to expand First Amendment protection from state laws, so that they can shield themselves from laws regulating social media’s targeting of children, antitrust laws, and AI regulation. They thought they had found a perfect pair of vehicles to further that expansion through these two badly crafted laws. Texas’s law banned social media companies with 50 million or more users from removing or demoting posts based on the view expressed in the post, or the viewpoint of the poster. The law also required social media platforms to disclose their content-moderation policies. Florida’s law limited social media platforms’ ability to demonetize, remove, or otherwise restrict political candidates and journalistic outlets and prohibited the platforms from attaching labels to user-generated content.

Big Tech is trying to spin this case as a win, because it wants to chill the imagination and energy of state lawmakers. But when they decided to sue, seeking a broad, big shield from state legislation, the tech companies shot for the moon and, thankfully, fell short.

With Justices Barrett and Jackson in the driver’s seat, we can actually see a glimmer of hope, a “sliver of optimism,” that there are new alignments on the court—especially around Big Tech and corporate speech. Jackson, Barrett, Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch may end up forming a formidable alliance, where skepticism of Big Tech dominance of the public sphere (Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch) marries a distaste for corporate speech rights to a Gen-X understanding of the technology (Jackson and Barrett).

Given the last two weeks of truly terrible Supreme Court opinions, progressives should count this decision as a win.

Thank you for reading The Nation

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply-reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Throughout this critical election year and a time of media austerity and renewed campus activism and rising labor organizing, independent journalism that gets to the heart of the matter is more critical than ever before. Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to properly investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories into the hands of readers.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

Zephyr Teachout

Zephyr Teachout, a Nation editorial board member, is a constitutional lawyer and law professor at Fordham University and the author of Break ’Em Up: Recovering Our Freedom From Big Ag, Big Tech, and Big Money.

More from The Nation

Under this new standard, a president can go on a four-to-eight-year crime spree and then retire from public life, never to be held accountable.

Elie Mystal

To preserve President Biden’s legacy, the party has to find another candidate

Jeet Heer

The court has given itself nearly unlimited power over the administrative state, putting everything from environmental protections to workers’ rights at risk.

Elie Mystal

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Snyder is baffling—so long as we ignore a desire by the justices to minimize the extent of their own corrupt conduct.

Zephyr Teachout

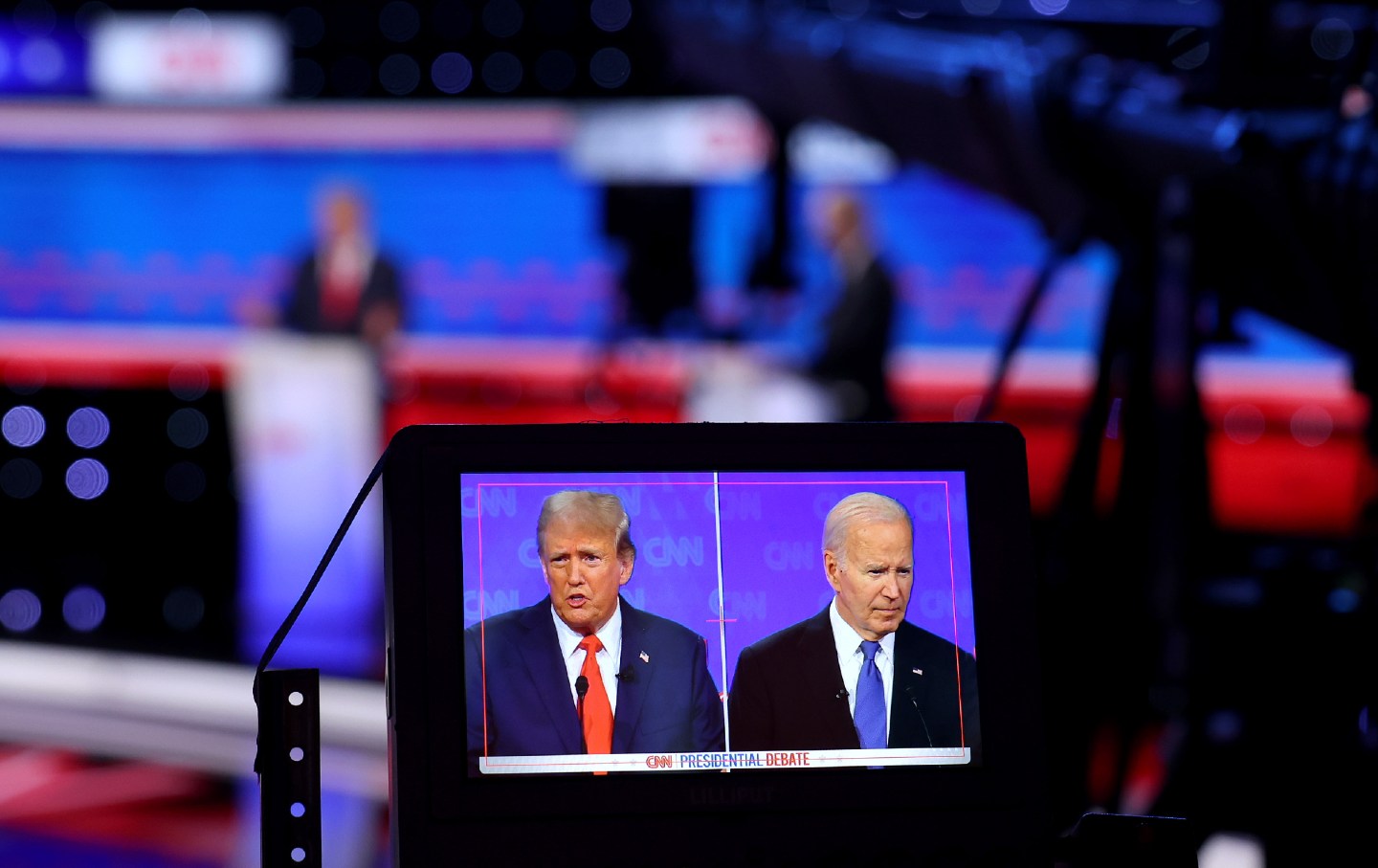

Trump’s lies and unhinged ranting went unchallenged because Biden was incoherent and lost.

Jeet Heer

[ad_2]