When I was a kid, the solar system was simple. There were nine planets and they all orbited in more-or-less circles around the sun. This same sun-and-a-handful-of-planets scheme repeated itself again and again throughout our galaxy, and these galaxies make up the universe. It’s a great story that’s easy to wrap your mind around, and of course it’s a great first approximation, except maybe that “nine planets” thing, which was just a fluke that we’ll examine shortly.

What’s happened since, however, is that telescopes have gotten significantly better, and many more bodies of all sorts have been discovered in the solar system which is awesome. But as a casual astronomy observer, I’ve given up hope of holding on to a simple mental model. The solar system is just too weird.

The Ancients and the Asteroids

It’s probably all Plato’s fault. While all of the ancient astronomers, from the Babylonians to the Egyptians, had noticed that some of the stars seemed to wander around relative to the others, it was Plato who posited that the fixed stars were located on one sphere, and the planets on another. That’s about as simple as you can get.

Ptolemy noticed that some of the planets seemed to wiggle around in their wanderings, and broke the planetary sphere by claiming that planets followed epicycles, and that each planet had its own. Others proposed epicycles on the epicycles, fitting the data better, but making for a very complicated system. Copernicus later managed to shrink the epicycles, explaining the motion of the planets by putting the sun at the center of the solar system. But it wouldn’t be until Kepler that we had a truly simple system again: all six planets, now including the earth, all orbited the sun in ellipses. Neat and tidy; the opposite of weird.

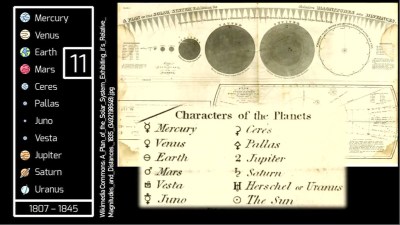

When the seventh planet, Uranus, was discovered, it was only a minor complication: just one more of the same thing that we already understood. Ditto the eighth planet, Ceres, in 1801. And then the ninth, Pallas, in 1802. And then the tenth planet, Juno, in 1804 and the eleventh, Vesta in 1807. Wait, what?

Today, we’d call these four planets “asteroids”, but for around 50 years, they were legit planets in their own right – except they all shared essentially the same orbit, which didn’t fit our mental schema at all. I don’t know if it was with relief or exasperation that as many, many more objects were discovered in the 1850, they all got collectively demoted from their “planet” status, and never spoken of in grade-school astronomy classes again. Our mental model of the solar system was simple once more.

But the asteroids are awesome. Vesta, for instance, suffered a gigantic collision, and over 15,000 tiny asteroids are thought to be chunks that split off, some of which rain down on the earth as meteorites. In that way, Vesta is the poster child of the weird solar system, even among the poster-children asteroids. And this is why NASA sending recent probes to Psyche and to the Trojan asteroids is particularly exciting.

Pluto and the TNOs

In the same era as the asteroid discoveries, the solar system’s eighth and outermost planet, Neptune, was discovered. The geopolitics of its discovery are a fascinating subject, but as far as our mental model of the solar system goes, it was just another planet.

Then comes Pluto. Discovered in 1930, it was a planet until 2006. It was a planet when I was a kid, and even though its orbit crossed inside of Neptune’s, we never gave it any thought. Its orbit takes it between 30 and 50 times as far from the sun as the earth and takes around 250 years. It’s a strange fluke of history that we discovered it just as telescopes were getting powerful enough, and as it was approaching closely. But for 76 glorious years, we convinced ourselves that it was a planet, because nine didn’t seem like too many.

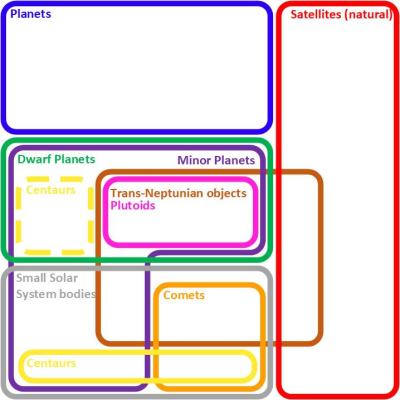

Until, like with the asteroids, we discovered more of them. Telescopes and their sensors became powerful enough in the late 1990s and early 2000s to start to resolve more of what we now call trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). And there are a lot of them. There is a tremendous variety of objects out there in the Kuiper Belt – a disc like the asteroid belt, only something like 100 times more massive. The Kuiper Belt is home to things like the close comets that have incredibly elliptical orbits that bring them close enough in to us to be visible, but also dwarf planets that are large enough to be rounded by their own gravity, and some of which even have moons.

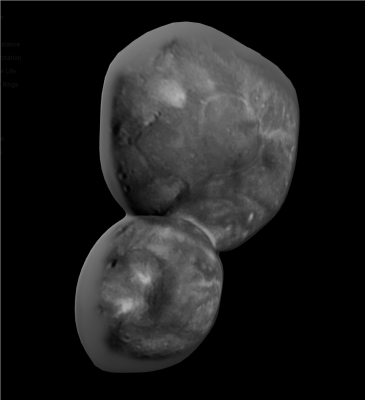

It’s only luck, and the fact that Pluto is very reflective, that we found it first. If human telescope development were delayed by a hundred years, it would have been further out, and maybe another TNO would have been discovered first. For instance, Eris is bigger, heavier, and since New Horizons flew by Pluto is the largest body in the solar system that we haven’t visited. (Arrokoth, another TNO, also got the New Horizons treatment, and is probably the strangest object that we’ve visited.)

The point with the TNOs: just outside the radius of what shows up on my son’s poster of the solar system are thousands of known objects, and potentially tens or hundreds of thousands of unknown objects that are big enough to be seen with today’s telescopes. Some are “planets” even if they’re not planets, some are comets, some need classification. But things are weird in the Kuiper Belt.

Centaurs

Closer to home, between the orbits of Jupiter and Neptune, we find the centaurs, so named because they’re halfway between asteroids and comets, and halfway between the asteroid belt and the Kuiper belt.

Like Pluto, the first centaur that was ever discovered was quickly called a planet in the popular press, upon its discovery in 1977. This “tenth planet” was named Chiron. (I take the irony that neither the ninth nor the tenth planet would hold up more than 30 years as strong evidence for the weird-solar-system hypothesis.) From recent telescope images, Chiron even looks like it has a ring system.

Like the TNOs, there are very many known centaurs, with the vast majority discovered since 2010. And like the TNOs, we owe our knowledge of the centaurs to increased telescope performance. The Hawaiian Pan-STARRS project has found about half of them. Some think that Saturn’s moon Phoebe is a captured centaur, or that the previously-eighth-planet Ceres used to be one.

With the discovery of the centaurs, the weird zones of the solar system were no longer limited to the asteroid belt in the middle and the Kuiper belt on the “outside”, but also the centaurs that are whizzing around between the two.

Strange Moons and Near-Earth Objects

Surely nothing is weird about the solar system closer to home than the asteroids, right? For instance, in our orbit it’s just us and the moon, right? Well, that depends on your definition of “moon”.

Kamoʻoalewa appears to be a chunk of our actual moon that got chipped off millions of years ago, but has been trapped by Earth’s gravity for more than a century. Given the dynamics, Kamo’oalewa will be with us for at least another 100 years. China’s Tianwen-2 mission may go visit Kamo’oalewa, and then we’d know for sure if it’s made out of moon.

Kamo’oalewa isn’t our only quasi-satellite: 2023 FW13 appears to be circling the earth stably in an orbit that runs roughly between halfway to Venus and Mars respectively. (Note the Hawaiian names? That’s Pan-STARRS again.) So don’t say “moon”, but maybe “quasi-moon”. These weird objects are new enough that we don’t have a name pinned down yet, but we will almost certainly discover more of them in the near future.

Additionally, it turns out that of the roughly 12 million asteroids that we know the orbits for, some 35,000 are on orbits that put them inside 1.3 AU of the sun. (One astronomical unit is the radius of the earth’s orbit around the sun.) Of these, roughly 1,600 have a non-zero probability of colliding with the earth.

Indeed, the second-closest flyby of the earth took place just two weeks ago. (Spoiler: it missed.) 2024 LH1 was visibly spinning as it passed overhead, which was observed by it “blinking” 3.7 times per second. The closest recorded approach was back in 2020, and it missed us by only 370 km. It probably would have disintegrated in the atmosphere, but as with the TNOs and the centaurs, it’s a testament to our telescopes that this near miss was noticed at all. The fastest flyby? That would be totally-not-a-spaceship ’Oumuamua.

The Weird Universe

As with all simple models, the planets-orbiting-the-sun model of the solar system is incomplete. Over the past two hundred years, more planets have been added and subtracted from the list than we have planets at all. But it’s not just the planets – the reason for kicking Ceres, and later Pluto, off the list was the discovery of entirely new classes of objects that are hundreds to millions of times more numerous than just eight or nine planets. And we’re finding them everywhere we look, not just in the “belts”. As our observational astronomy gets better and better, the solar system gets weirder and weirder, and the last twenty years have seen the weirding accelerate.

And that’s just the solar system. Don’t get us started on the rogue planets that wander around completely untethered from any suns at all. There’s a lot more going on out there than we know, or than our orderly systems like to admit. At this point in astronomy, it’s more likely that we’ll discover an entirely new class of objects than a ninth planet. So, keep looking up and keep your mind open. Help keep the universe weird!