Although it’s often said that the era of ocean liners came to an end by the 1950s with the rise of commercial aviation, reality isn’t quite that clear-cut. Coming out of the troubled 1940s arose a new kind of ocean liner, one using cutting-edge materials and propulsion, with hybrid civil and military use as the default, leading to a range of fascinating design decisions. This was the context in which the SS United States was born, with the beating heart of the US’ fastest battle ships, with light-weight aluminium structures and survivability built into every single aspect of its design.

Outpacing the super-fast Iowa-class battleships with whom it shares a lot of DNA due to its lack of heavy armor and triple 16″ turrets, it easily became the fastest ocean liner, setting speed records that took decades to be beaten by other ocean-going vessels, though no ocean liner ever truly did beat it on speed or comfort. Tricked out in the most tasteful non-flammable 1950s art and decorations imaginable, it would still be the fastest and most comfortable way to cross the Atlantic today. Unfortunately ocean liners are no longer considered a way to travel in this era of commercial aviation, leading to the SS United States and kin finding themselves either scrapped, or stuck in limbo.

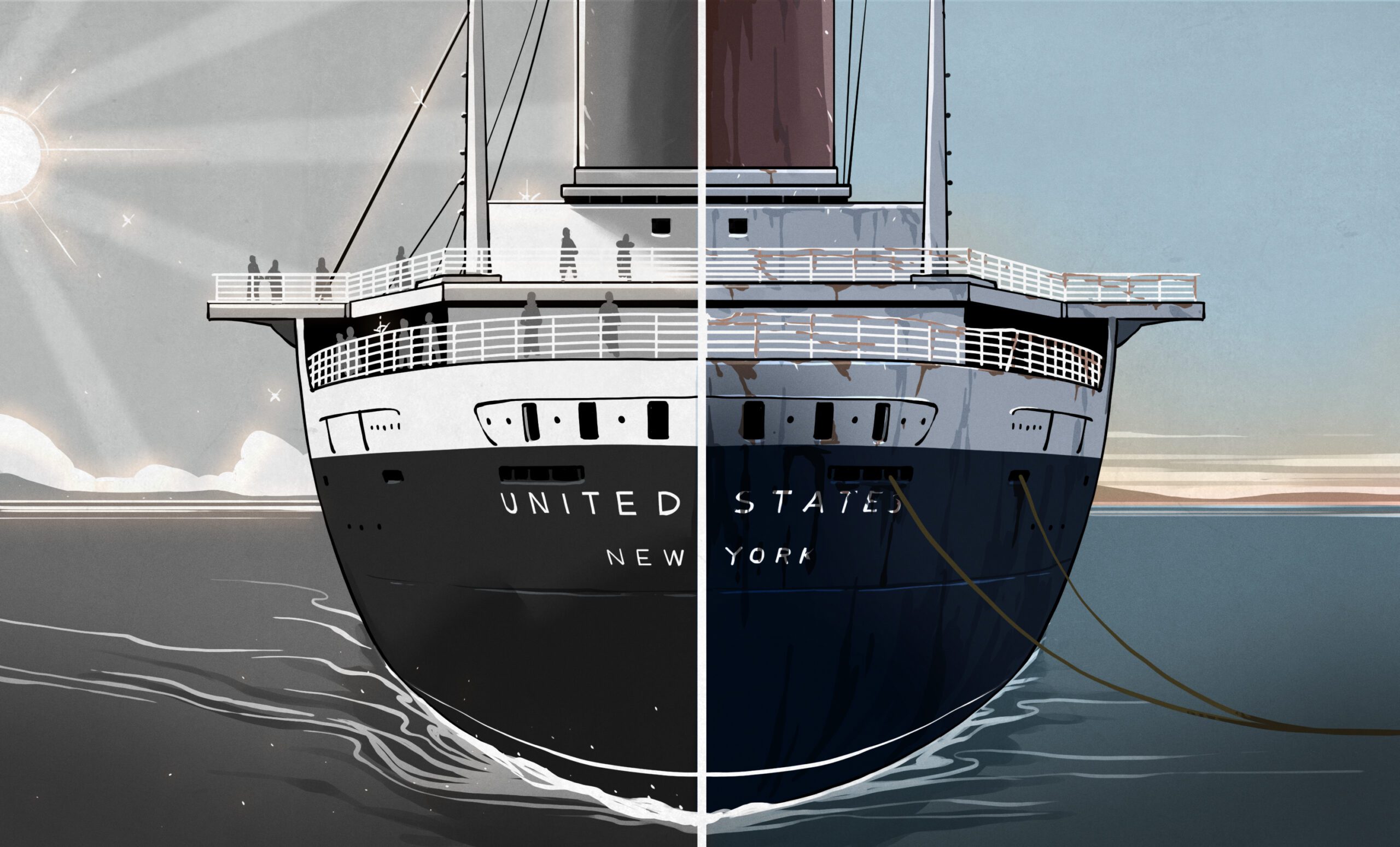

In the case of the SS United States, so far it has managed to escape the cutting torch, but while in limbo many of its fittings were sold off at auction, and the conservation group which is in possession of the ship is desperately looking for a way to fund the restoration. Most recently, the owner of the pier where the ship is moored in Camden, New Jersey got the ship’s eviction approved by a judge, leading to very tough choices to be made by September.

A Unique Design

The designer of the SS United States is William Francis Gibbs, who despite being a self-taught engineer managed to translate his life-long passion for shipbuilding into a range of very notable ships. Many of these were designed at the behest of the United States Maritime Commission (MARCOM), which was created by the Merchant Marine Act of 1936, until it was abolished in 1950. MARCOM’s task was to create a merchant shipbuilding program for hundreds of modern cargo ships that would replace the World War I vintage vessels which formed the bulk of the US Merchant Marine. As a hybrid civil and federal organization, the merchant marine is intended to provide the logistical backbone for the US Navy in case of war and large-scale conflict.

The first major vessel to be commissioned for MARCOM was the SS America, which was an ocean liner commissioned in 1939 and whose career only ended in 1994 when it (then named the American Star) wrecked at the Canary Islands. This came after it had been sold in 1992 to be turned into a five-star hotel in Thailand. Drydocking in 1993 had revealed that despite the advanced age of the vessel, it was still in remarkably good condition.

Interestingly, the last merchant marine vessel to be commissioned by MARCOM was the SS United States, which would be a hybrid civilian passenger liner and military troop transport. Its sibling, the SS America, was in Navy service from 1941 to 1946 when it was renamed the USS West Point (AP-23) and carried over 350,000 troops during the war period, more than any other Navy troopship. Its big sister would thus be required to do all that and much more.

Need For Speed

William Francis Gibbs’ naval architecture firm – called Gibbs & Cox by 1950 after Daniel H. Cox joined – was tasked to design the SS United States, which was intended to be a display of the best the United States of America had to offer. It would be the largest, fastest ocean liner and thus also the largest and fastest troop and supply carrier for the US Navy.

Courtesy of the major metallurgical advances during WW II, and with the full backing of the US Navy, the design featured a military-style propulsion plant and a heavily compartmentalized design following that of e.g. the Iowa-class battleships. This meant two separate engine rooms and similar levels of redundancy elsewhere, to isolate any flooding and other types of damage. Meanwhile the superstructure was built out of aluminium, making it both very light and heavily corrosion-resistant. The eight US Navy M-type boilers (run at only 54% of capacity) and a four-shaft propeller design took lessons learned with fast US Navy ships to reduce vibrations and cavitation to a minimum. These lessons include e.g. the the five- and four-bladed propeller design also seen used with the Iowa-class battleships with their newer configurations.

Another lessons-learned feature was a top to bottom fire-proofing after the terrible losses of the SS Morro Castle and SS Normandie, with no wood, fabrics or other flammable materials onboard, leading to the use of glass, metal and spun-glass fiber, as well as fireproof fabrics and carpets. This extended to the art pieces that were onboard the ship, as well as the ship’s grand piano which was made from mahogany whose inability to ignite was demonstrated by trying to burn it with a gasoline fire.

The actual maximum speed that the SS United States can reach is still unknown, with it originally having been a military secret. Its first speed trial supposedly saw the vessel hit an astounding 43 knots (80 km/h), though after the ship was retired from the United States Lines (USL) by the 1970s and no longer seen as a naval auxiliary asset, its top speed during the June 10, 1952 trial was revealed to be 38.32 knots (70.97 km/h). In service with USL, its cruising speed was 36 knots, gaining it the Blue Riband and rightfully giving it its place as America’s Flagship.

A Fading Star

The SS United States was withdrawn from passenger service by 1969, in a very unexpected manner. Although the USL was no longer using the vessel, it remained a US Navy reserve vessel until 1978, meaning that it remained sealed off to anyone but US Navy personnel during that period. Once the US Navy no longer deemed the vessel relevant for its needs in 1978, it was sold off, leading to a period of successive owners. Notable was Richard Hadley who had planned to convert it into seagoing time-share condominiums, and auctioned off all the interior fittings in 1984 before his financing collapsed.

In 1992, Fred Mayer wanted to create a new ocean liner to compete with the Queen Elizabeth, leading him to have the ship’s asbestos and other hazardous materials removed in Ukraine, after which the vessel was towed back to Philadelphia in 1996, where it has remained ever since. Two more owners including Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) briefly came onto the scene, but economic woes scuttled plans to revive it as an active ocean liner. Ultimately NCL sought to sell the vessel off for scrap, which led to the SS United States Conservancy (SSUSC) to take over ownership in 2010 and preserve the ship while seeking ways to restore and redevelop the vessel.

Considering that the running mate of the SS United States (the SS America) was lost only a few years prior, this leaves the SS United States as the only example of a Gibbs ocean liner, and a poignant reminder of what would have been a highlight of the US’s marine prowess. Compared to the United Kingdom’s record here, with the Queen Elizabeth 2 (QE2, active since 1969) now a floating hotel in Dubai and the Queen Mary 2‘s maiden voyage in 2004, the US looks to be rather meager when it comes to preserving its ocean liner legacy.

End Of The Line?

The curator of the Iowa-class USS New Jersey (BB-62, currently fresh out of drydock), Ryan Szimanski, walked over from his museum ship last year to take a look at the SS United States, which is moored literally within viewing distance from his own pride and joy. Through the videos he made, one gains a good understanding of both how stripped the interior of the ship is, but also how amazingly well-conserved the ship is today. Even after decades without drydocking or in-depth maintenance, the ship looks like could slip into a drydock tomorrow and come out like new a year or so later.

At the end of all this, the question remains whether the SS United States deserves it to be preserved. There are many arguments for why this would the case, from its unique history as part of the US Merchant Marine, its relation to the highly successful SS America, it being effectively a sister ship to the four Iowa-class battleships, as well as a strong reminder of the importance of the US Merchant Marine at some point in time. The latter especially is a point which professor Sal Mercogliano (from What’s Going on With Shipping? fame) is rather passionate about.

Currently the SSUSC is in talks with a New York-based real-estate developer about a redevelopment concept, but this was thrown into peril when the owner of the pier suddenly doubled the rent, leading to the eviction by September. Unless something changes for the better soon, the SS United States stands a good chance of soon following the USS Kitty Hawk, USS John F. Kennedy (which nearly became a museum ship) and so many more into the scrapper’s oblivion.

What, one might ask, is truly in the name of the SS United States?