[ad_1]

Books & the Arts

/

August 27, 2024

The surprising origins and politics of equality

A series of new books unearth the long history of egalitarian politics. They also ask whether equality, instead of another political ideal, should be at the center of our politics?

In the chilling speech he gives at the end of the film Margin Call, Jeremy Irons says that no one should say they believe in equality, because no one really thinks it exists: The very idea camouflages the endurance of hierarchy in an essentially unchanging form. “It’s certainly no different today than it’s ever been,” he explains to an underling. “There have always been and there always will be the same percentage of winners and losers….

Yeah, there may be more of us than there’s ever been, but the percentages? They stay exactly the same.”

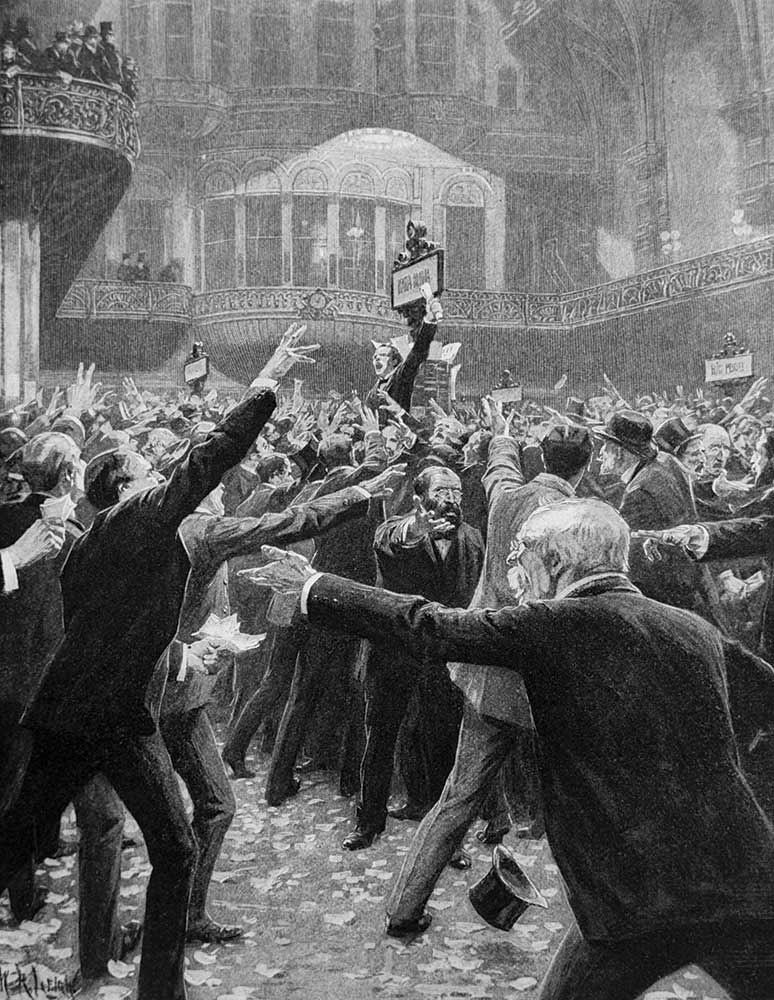

For many others, the response to the 2008 financial crisis was very different from Irons’s cynical response. The crisis led to more consciousness and criticism of inequality than had been seen in the past 50 years. Starting with Occupy Wall Street in 2011, large numbers of Americans concerned about the ascendancy of the “1 percent” eventually consolidated around Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaigns in 2016 and 2020. During these years, the French economist Thomas Piketty provided the reading public with evidence that vindicated the movement: In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, published in English in 2014, he confirmed that economic inequality had been rising across the North Atlantic world. Piketty also showed that the situation was simultaneously worse and better than the way Irons had characterized it in Margin Call: Capitalism’s inherent dynamics generally increased inequality, he argued, but political mobilizations could bring about its reduction.

Capital in the Twenty-First Century became a surprise bestseller, and inequality became a signature concern of the new century, analyzed and complained about (and, more rarely, justified) in a deluge of articles, books, and tweets. But a decade later, historians, economists, and political theorists are pondering a different set of questions: not about the causes or continued existence of our age of inequality, but about where the moral imperative for its opposite—equality—came from in the first place. In A Brief History of Equality, Piketty offered his own views, emphasizing how the egalitarian distribution of income and wealth in the mid–20th century has been reversed in our neoliberal era. But over the past year, a new wave of books has appeared that fundamentally broaden the terms of this now-standard account. Darrin McMahon’s ambitious Equality puts modern concerns about class disparity in their historical place. Paul Sagar’s Basic Equality provides an account of how the belief that all men are created equal emerged in the early modern period—an inquiry that Teresa Bejan also takes up in “What Was the Point of Equality?” and that will feature in her forthcoming First Among Equals. And David Lay Williams, in The Greatest of All Plagues, examines how canonical thinkers from Plato to Karl Marx took up the subject of economic hierarchy in their own work. Each of these books helps answer the question of where the ideal of equality came from. But posing that question leads to an even more pressing one: whether equality is the most important thing to begin with.

In Equality, McMahon gives us an astonishingly capacious history. It is a monument to his ability—previously demonstrated in his books on genius and happiness—to synthesize historical findings across millennia. Narrating what his “Big History” compatriot Peter Turchin has called the “Z-Curve” of egalitarianism, McMahon charts how equality has zigged and zagged throughout human history. Our hominid ancestors, he writes, were as indentured to hierarchy as the higher primates are today. Then humans developed more cooperative ways of living that moderated such domination. That was the zig. Then a massive step backward was taken with the Neolithic Revolution a little more than 10,000 years ago. During this period, a growing reliance on agriculture meant that human society required cadres of workers, and early states began elevating nobles and kings. That was the zag. Generalizing hugely, the trend of history since then has been more favorable to equality.

In telling this story, McMahon examines the Greek political miracle, religions like Christianity (especially the Reformation), the Enlightenment, and the revolutions that followed. Far from stopping there, he finishes his account by examining contemporary movements for class, gender, and racial justice both locally and globally, along with movements (from the past and in the present) that call for in-group equality.

Current Issue

Well-known for his expertise on 18th-century France, McMahon is right to focus on that time and place, and not only because it produced the greatest egalitarian in the history of philosophy, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The Enlightenment was the dawn of our own age, reactivating ancient traditions of equal political status and citizenship and making Rousseau immortal for his concerns about excessive class inequality. It also helped lay the groundwork for political revolutions on both sides of the Atlantic and a body of laws that sought to represent the will of free men (though not women, whom Rousseau hated) and that could moderate economic and social inequalities.

Even as he chronicles this period, however, McMahon is surprisingly grudging about the French Revolution’s catalyzing effect on the spread of equality in subsequent history. He notes that the events of 1789 helped spark a new set of claims by and on behalf of the enslaved, Jews, and women in Europe and the Americas. But he downplays the pioneering Jacobin welfare measures that were established during the revolution, while worrying that the era’s “sanctification” of equality inevitably meant punishing the “unregenerate.”

As amazing an achievement as McMahon’s book is, his very ambition forces him to tell competing and potentially contradictory stories, sometimes giving the impression that he thinks they add up to a single, coherent whole. The equality within hunter-gatherer tribes found in what the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins called “the original affluent society” doesn’t mean that our ancestors were ideologically committed to equality. Christians, on the other hand, were, but saying that all people are equal in the eyes of God by no means implies political and economic equality. Equal circumstances may not depend on ideological commitment; nor do ideologies of equality imply any demand for more particular forms of equality in fact. Indeed, Christianity made it easy to say that everyone is of equal worth in God’s sight precisely because not much necessarily followed from it. In our post-Christian era, many still deny a connection between the social dimensions of equality—being seen as equal in social or political status—and equality in how the good things in life are distributed.

McMahon’s story is forced to cover all of these distinctions, charting how the different contributions across the centuries are really just about one or another kind of equality; there is no such thing, it turns out, as equality as such. His book is valuable precisely because it comes close to collapsing under the weight of its ambition to consolidate the history of equality in all its multifariousness. That also makes it a good thing that a group of scholars has added pointillistic detail about two crucial zaglets in McMahon’s millennia-long story—one that made it possible to conceive of humans as being equal in the first place, and another that made it possible to say that disparity in how much people earn and own might be wrong.

For Paul Sagar, in his new book Basic Equality, the origins of what we might call ideological equality—the idea that all human beings are equal—remain mysterious. From Plato on, Sagar contends, political theory has centered on the idea of natural difference, emphasizing disparities among humans that seemed deep and ineradicable. Men and women, for example, have been treated as so different for so long that their disparate treatment was considered the way of the world, while phenotypical variations in skin color—never entirely insignificant—became more consequential in modern times. What, then, could make the belief that everyone is equal not just credible but hegemonic, no matter how disregarded in practice?

A generation ago, the philosopher Jeremy Waldron argued that only religious dogma could furnish such a belief. Sagar worries that everyone else (unbelievers as well as Christians who didn’t get the memo) needs to understand why they are committed to equality. But rather than looking for some enduring feature of humanity—our rational faculty, or immortal soul, or physical vulnerability—to justify equality, Sagar argues that it is far better to think of it as a social fiction that humans came to believe, first in Christian form and later in a secular guise. And, he continues, we should not disguise how recently this fiction became popular. (Some might doubt that it ever fully did.)

As brilliant as Sagar’s case is, his focus on the basic equality of human beings says nothing about the rise of the contentious politics of equalization in modern times. After all, the Christian and later secular belief that everyone is in some sense morally equal has generally been compatible with massive inequalities in standing, treatment, and wealth. In fact, humans have had to learn over and over again the idea that they are equal (which Sagar thinks is worth doing). But that doesn’t explain when and why they did, or how they could treat one another so unequally despite such a belief.

Much like McMahon, Teresa Bejan is careful to distinguish between how thinkers conceptualized equality in the ancient world and how they saw it in modern times, focusing on the rise of “parity”: the idea that people in a society ought to be treated as on par. Where notions of equality presuppose sameness, treating people in a “paritarian” spirit presupposes difference. In her discussion of 17th-century England in “What Was the Point of Equality?,” for example, Bejan shows how almost everyone accepted the idea of equality in a post-feudal world: Everyone (at least every white man) was created equal in some sense. But radical groups like the Diggers and the Levellers aimed for something more than equality; they wanted parity between different groups of equal men. According to Bejan, they and their successors in egalitarian movements today speak in a language of equality, but what they want is something more specific: the treatment that some already have and that others should also receive. Equality was and is compatible with disparate treatment, Bejan notes. Parity, on the other hand, insists on placing previously subordinated people on the higher level of the privileged.

Oriented more toward concerns about basic status, neither Bejan nor Sagar examines the left-wing anger toward economic hierarchy and why it, in particular, became pivotal not just for small groups like the Levellers but also for millions in modern times—or why Occupy, “Pikettymania,” and Sanders helped revive a consciousness of it. This question sits at the center of David Lay Williams’s excellent new survey, The Greatest of All Plagues.

Williams says his goal in the book is to draw attention to something that has long been missed: that the West’s canonical political thinkers, not just its lowly workers, have been persistent critics of accumulated wealth. While he starts with Plato and the New Testament, it is his discussion of Rousseau, Marx, and John Stuart Mill that helps Williams register the continuities and changes in reasoning about economic inequality. Plato may have been committed to notions of natural difference, but he was also anxious, Williams observes, about the consequences of too much money concentrated in too few hands and the threats posed by too much poverty to political stability. Rousseau vividly stressed the political costs of economic inequality—especially wealth passed from generation to generation, which established a permanent form of privilege. Even to Plato, it was obvious that envy, if allowed to become supercharged, would fuel a dangerous unrest. But for Rousseau, the dangers went further: The economic inequality of the 18th century’s new era of commerce and opulence also threatened other forms of equality.

Ad Policy

Like McMahon, Williams discusses Marx at length in his study. It might still surprise some that Marx made so little of equality—certainly when compared with Rousseau, let alone Gracchus Babeuf, who is often credited as the first communist and called for a “conspiracy of equals” to rescue the French Revolution’s ideals. As McMahon observes, the word “equality” appears just once in The Communist Manifesto, and in a derogatory way. Whereas Rousseau focused constantly on economic inequality as an enormous problem of modern commercial societies, Marx did not. Rather, his concern was unfreedom, especially the alienation of our powers to others in an extractive labor process over which workers have no control.

Williams concedes that freedom is Marx’s preeminent goal, but he also suggests that “Marx’s concern with the problem of extreme economic inequality is a powerful animating principle underlying his critical and constructive political philosophy.” Fair enough: As the contemporary analyst of global inequality Branko Milanović discusses in his own recent survey of modern economists, Visions of Inequality, the North Atlantic of Marx’s era saw a greater and greater disparity in wealth—with the top 1 percent owning 60 percent of wealth in the United Kingdom, for example—and it is natural that economic inequality would serve as a backdrop for his thinking. But this makes it only more important that Marx considered inequality a problem not in itself but because it signaled and symbolized unfreedom: An unequal society is likely to be an unfree one too. But ultimately, for Marx, exploitation—not inequality—is the worst thing that humans can do to one another.

More from Books & the Arts

No wonder, then, that Marx’s theory of political economy encompassed a full-scale interpretation of capitalism. He didn’t fixate single-mindedly on the 1 percent, but instead dedicated Capital to the study of everything from the labor process to the systemic dynamics that he thought would unleash political revolution. By the same token, he presumed that communist emancipation might well allow for some inequalities in what people have and get, so long as this remained consistent with free social relations. As McMahon observes, both Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin, faithful to their master, dismissed “equality mongering,” especially if it meant a bourgeois prattling about unfairness that was not willing to entertain the abolition of classes.

Marxist or not, Marx’s point is momentous for closing our decade of concern with inequality. McMahon’s big conclusions from his millennial survey are disarming and depressing. Telling the grand story of equality’s formation over human history, he prefers to stress that equality and inequality are necessarily intertwined—most frighteningly in his chapter on fascism, which sought an equality within the Aryan “race” while exterminating outcasts. (“The uniform makes all men equal,” proclaimed Der Angriff, the National Socialist newspaper.)

McMahon contends that some forms of inequality will persist no matter what kind of egalitarian society a community seeks; humans have evolved with an ambivalence toward equal standing, he argues, precisely because so much turns on competitive preeminence. Whatever the equalities established in a given society, it will always contain some hierarchies, too. If people are never going to be equal in every respect, McMahon continues, then various forms of inequality will persist and perhaps worsen, even as other forms are minimized.

These conclusions of our greatest historian of equality so far are arresting, but what really matters, as Marx said, is eliminating the inequalities that matter. Equality both of status and distribution were breakthroughs, and anger when they are reversed is one of the most promising developments of late. This doesn’t mean that society can or should reach full equality along all dimensions, whatever that might mean. But, as Marx concluded, it must involve getting clear about when and in what forms inequality is an eradicable injustice, something to mobilize against in the name of emancipation and freedom. A few months ago, the historian Quinn Slobodian dismissed the whole concern with inequality since Piketty. It is, Slobodian argued, a diversionary obsession of what the French economist himself called the “Brahmin left”—that is, “highly educated people willing to consume critiques of the system while remaining too materially committed to risk its transformation.”

I am a little more forgiving about the spate of books on inequality—I wrote one myself. But there’s another reason too: The concern with inequality is like a stepping stone to a higher perspective, which means welcoming these histories of inequality for helping readers move beyond their own terms. After all, they force us to decide what deeper problems—including unfreedom on a local and global scale—are even more important.

Can we count on you?

In the coming election, the fate of our democracy and fundamental civil rights are on the ballot. The conservative architects of Project 2025 are scheming to institutionalize Donald Trump’s authoritarian vision across all levels of government if he should win.

We’ve already seen events that fill us with both dread and cautious optimism—throughout it all, The Nation has been a bulwark against misinformation and an advocate for bold, principled perspectives. Our dedicated writers have sat down with Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders for interviews, unpacked the shallow right-wing populist appeals of J.D. Vance, and debated the pathway for a Democratic victory in November.

Stories like these and the one you just read are vital at this critical juncture in our country’s history. Now more than ever, we need clear-eyed and deeply reported independent journalism to make sense of the headlines and sort fact from fiction. Donate today and join our 160-year legacy of speaking truth to power and uplifting the voices of grassroots advocates.

Throughout 2024 and what is likely the defining election of our lifetimes, we need your support to continue publishing the insightful journalism you rely on.

Thank you,

The Editors of The Nation

Samuel Moyn

Samuel Moyn teaches law and history at Yale. His most new book is Humane: How the United States Abandoned Peace and Reinvented War (Macmillan).

More from The Nation

Despite claiming to support AI safety, powerful tech interests are trying to kill SB1047.

Lawrence Lessig

Extreme heat has long been a concern for incarcerated pregnant women and those behind bars with underlying health conditions.

Victoria Law

![On Feb. 27, 2013, just a few hours after Solicitor General Donald Verrilli endeavored to protect the Voting Rights Act before the U.S. Supreme Court, he dropped by his boss’s office and told US Attorney General Eric Holder that arguments in the case, Shelby County v. Holder, had gone poorly. Verrilli warned Holder things might be worse than they feared: The Court intended to go after the entirety of preclearance, the VRA’s most crucial enforcement mechanism. Holder scarcely believed that could be possible. “The Voting Rights Act? Come on,” Holder said. But to the veteran solicitor general, recovering from the most brutal experience he’d ever had before the Court, the writing was on the wall. “I walked out of that courtroom certain that’s what was going to happen,” Verrilli told me. “I was never optimistic at all.” Verrilli had underestimated how meticulously John Roberts had planned for this moment. He never imagined that he’d be hit with such mendacious numbers and arguments in a sanctum he revered. And though his pessimism turned out to be abundantly justified, the dishonest reasoning behind Roberts’s decision – that the chief justice could just conjure a doctrine of his own creation and use it to eviscerate the most important civil rights legislation in the nation’s history – haunts the solicitor general to this day. It has remade American democracy as well. [dropcap]J[/dropcap]ohn Roberts had schemed for decades prior to this moment. Three years earlier, a test case known as Northwest Austin allowed Roberts to carefully plant the seeds for the challenge that foes of voting rights law mounted in Shelby County. A tiny municipal water board in a new Texas development posed a large constitutional question. The VRA’s preclearance regime required every locality in the state to -approve in advance any changes to voting procedures through the Department of Justice. Preclearance worked to right historical wrongs: The VRA mandated it in the handful of states and localities with the worst records of racial discrimination in elections; when Congress reauthorized the Voting Rights Act by near-unanimous margins in 2006, it relied on a record of ongoing modern chicanery stretching toward 14,000 pages, bearing eloquent testimony to the ongoing need for preclearance. Two lower federal courts had agreed that the utility district did not qualify for exemption from the VRA, and that preclearance itself remained a proportionate response by Congress. “The racial disparities revealed in the 2006 legislative record differ little from what Congress found in 1975,” wrote federal appeals Judge David Tatel. “In view of this extensive legislative record and the deference we owe Congress, we see no constitutional basis for rejecting Congress’s considered judgment.” Before Tatel wrote his decision, he read every page of the 2006 congressional report, and tracked the stories of canceled elections and last-second precinct switches across Mississippi, Louisiana and other covered states. He did so, he told me, because “I had no confidence that the Supreme Court would ever look at the record.” His fears were justified. On April 29, 2006, during the oral arguments over Northwest Austin, Roberts expressed impatience, and sounded as if he simply didn’t believe these challenges continued. “Well, that’s like the old elephant whistle. You know, I have this whistle to keep away the elephants,” he said, dismissively, as the defense pointed out the ongoing need for preclearance in the case. “There are no elephants, so it must work. “Obviously no one doubts the history here,” he added. “But at what point does that history stop justifying action with respect to some jurisdictions but not with respect to others . . . . When do they have to stop?” Neal Kaytal, then the principal deputy solicitor general, responded that since Congress had reauthorized the VRA for another 25 years, that date would be 2031. Roberts was unimpressed. “I mean, at some point it begins to look like the idea is that this is going to go on forever.” The court’s five conservatives wanted to move on, and several appeared ready to address the larger constitutional issues that would trigger a challenge the VRA, but didn’t have much beyond vibes to go on. So Roberts brokered a deal, and wrote an apparently unifying decision for a court that appeared deeply divided during oral arguments. Everybody won, sort of. The water district would be allowed to bail out of preclearance requirements. Other small entities were invited to apply for a reprieve. At the same time section 5—laying out the VRA’s preclearance regime— survived. The liberal justices bought time for Congress to potentially address the court’s impatience with the preclearance formula once more. “It wasn’t exactly a principled constitutional decision,” says Tatel, who had scoured the law to see if he could deliver a similar ruling that sanctioned a bailout for the water district, in part to keep the VRA away from the high court. But the law clearly didn’t allow it. (“It doesn’t work with the law. It’s not right,” he told me, “but that didn’t bother the court.”) “They made a deal,” says Edward Blum, who helped bring the challenge to the VRA, and would also mastermind the clutch of cases that led the court to end affirmative action in college admissions. Roberts seemed to have done the impossible, and he won praise from the media and court watchers for his measured and far-seeing “judicial statesmanship.” Liberals even claimed victory, crowing to The New Republic that they prevented the VRA from being struck down 5-4 by threatening some thunderous dissent that either led Justice Kennedy to get cold feet or the chief justice to back down. If the liberals wanted to celebrate an imaginary win, Roberts had no problem with that. The chief justice was busy digging a trench and setting a trap. Indeed, the liberal justices scarcely seemed to notice the actual language of the opinion that they signed onto. “Things have changed in the South,” Roberts declared, writing for the full court. The VRA, he wrote, “imposes current burdens and must be justified by current needs.” Roberts had conned the liberals into signing onto a broad indictment of the reasoning behind preclearance, aimed at a future case and a future decision. “The statute’s coverage formula is based on data that is now more than 35 years old,” Roberts argued, as though civil-right legislation had a sell-by date. “And there is considerable evidence that it fails to account for current political conditions.” Then Roberts made one additional stealth play that helped assure that the next challenge to the VRA would arise quickly and would be aided by the plaintiffs’ success in Northwest Austin. He made an observation known as dicta—a comment that might not be necessary to resolve a case or even be legally binding in the future, but that can be cited as a “persuasive authority.” This is where Roberts gave birth to the fiction of a “fundamental principle of equal sovereignty” among states. The trouble with the principle is that it does not exist. Roberts created it with an ellipsis and what can only be understood as deliberate misapplication of the law. Indeed, the Supreme Court had rejected this precise reading in a 1966 voting rights case that upheld the Act’s constitutionality, in the very sentence that Roberts later claimed said the opposite. How did he get away with turning up into down? He cut the clauses he didn’t like and called it law. Here is the actual decision from the case in question, Katzenbach v South Carolina: In acceptable legislative fashion, Congress chose to limit its attention to the geographic areas where immediate action seemed necessary . . . . The doctrine of the equality of States, invoked by South Carolina, does not bar this approach, for that doctrine applies only to the terms upon which States are admitted to the Union, and not to the remedies for local evils which have subsequently appeared. And here is what Roberts wrote: The Act also differentiates between the States, despite our historic tradition that all the States enjoy “equal sovereignty.” Distinctions can be justified in some cases. “The doctrine of the equality of States … does not bar … remedies for local evils which have subsequently appeared.” But a departure from the fundamental principle of equal sovereignty requires a showing that a statute’s disparate geographic coverage is sufficiently related to the problem that it targets. Before Roberts wrote this, there was no such principle—let alone a fundamental one. The cases that Roberts cites as authorities for the idea of equality among states actually concern the “equal footing doctrine,” which secures equality among newly admitted states. No fundamental principle of equality among states governs the Fifteenth Amendment, which explicitly hands Congress the power to enact appropriate legislation to ensure equal treatment of all voters within states. Liberal justices either didn’t notice the dicta or did not think that Roberts would be so brazen as to write it into law citing his own invented precedent the next time a preclearance case came before the court. They underestimated both his chutzpah and hubris. It would not be the first, or the last time. [dropcap]I[/dropcap]f Roberts weakened the VRA’s foundations in Northwest Austin, four years later, in Shelby County, he came with the bulldozer. The preclearance formula had become outdated and no longer considered “current conditions,” Roberts wrote, brushing aside the lengthy congressional record filled with modern-day examples. Singling out states for disparate treatment, he held, failed to accord each state its “equal sovereignty.” The decision appeared modest and suggested that the Court had little choice but to act. But the feigned modesty was pure misdirection. The Shelby County decision is a deeply radical one. It usurps powers the Constitution specifically awards Congress. It uses the fictional principle of equal sovereignty, cooked up by Roberts in 2009, as its basis. And it cites statistics that are factually wrong and misstate the U.S. census. In the wake of other draconian hard-right decisions, such Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health (2022), reversing the right to abortion, and Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024), striking down “chevron deference” and effectively undermining the authority of federal regulatory agencies, public confidence in the high court has plummeted. Large majorities of Americans see the justices as partisan proxies, viewing the law through whatever lens might create victories for their side. But even this disillusioned American majority may not suspect that the justices might just be making the law up as they go along—that their opinions carry footnotes and the force of law but stand on air. Nor do most Americans fully appreciate that five, and now six, of them can get away with this because they form a majority ideological bloc, accountable to no one. That’s the real story behind John Roberts’s opinion in Shelby County. The chief justice obliterated the most successful civil rights legislation this nation has ever seen not just on flimsy criteria but on none at all. “It’s made up,” the conservative judge and law professor Michael McConnell, a George W. Bush appointee, told NPR. “This is a principle of constitutional law of which I had never heard,” the conservative judge and legal scholar Richard Posner observed, “for the excellent reason that … there is no such principle.” “Yes, that’s right,” says Leah Litman, a law professor at the University of Michigan. “There are passing references to the idea of equal sovereignty. But if you pause and think about them for more than a second, it’s clear that [Roberts] made the doctrine into something that it just wasn’t.” Litman is the national authority on equal sovereignty. In 2016, she wrote a complete 67-page history of what Roberts called a “fundamental principle” and “historic tradition.” Her conclusion? Roberts manufactured it for his own purposes. It is, she writes, an “invented tradition”---invented by John Roberts, and then cited by John Roberts. What Roberts didn’t make up, he got wrong. Roberts based his reasoning that things had changed in the South on voter registration statistics that, to him, showed that Blacks and whites had reached something close to parity—and that in some states, Blacks had even surpassed whites. His opinion even included a chart ostensibly documenting this. In reality, though, Roberts had the statistics backward. They did not show what he said they did. In many cases, they showed the opposite. Roberts used the numbers from the Senate Judiciary Report—the one that Republicans generated after the VRA’s passage to plant a record for its judicial demise. And intentionally or otherwise, the GOP report got it wrong. Roberts and the committee overstated white registration numbers. The Roberts chart counted Hispanics as whites—even those who were not U.S. citizens and therefore ineligible to vote. That basic error threw off all the demographic comparisons. In Georgia, for example, Roberts claimed that Black registration had risen to 64.2 percent and white registration had fallen behind at 63.5. But without the Hispanic numbers, white registration grew to 68 percent. It’s an improvement from 1965. But it’s not an example of Black registration outpacing whites, as Roberts claimed. In Virginia, meanwhile, Roberts argued that the gap between whites and Blacks had narrowed to just 10 percent—when in reality, it was more than 14 percent. Roberts simply didn’t understand how the census reported race. The Bureau treats race and ethnicity differently. Hispanics are counted as an ethnicity, then usually included under white. The chief justice should have used the data for white-non-Hispanic. But that would not have given Roberts the result he wanted. When reporters asked the court to explain how he could have gotten something so basic so wrong, the chief justice declined to answer questions. The court “does not comment on its opinions,” said a spokesperson, “which speak for themselves.” [dropcap]“T[/dropcap]his was Congress’s decision to make,” solicitor general Verrilli told me—a power awarded explicitly by the Reconstruction amendments to the Constitution. Debo Adegbile, who defended the VRA before the court during both Shelby County and Northwest Austin, sees the long throughline of the Court’s resistance to the full sweep of those amendments. The court’s impatience with the past, its eagerness to declare the job complete and the nation whole, reminded him of the 1870s Cruikshank and Civil Rights Cases decisions that choked off Reconstruction and insisted Blacks must “cease to be the special favorites of the law” even as freed slaves carried scars of their bondage. “It’s just the continued resistance to the commitment to make the country whole and to be an inclusive democracy,” he told me. “And it’s being dressed up in sophisticated legal arguments. It’s not that we’re actually past anything. It’s that we are now at a point where we have the power to decide that we’re going to vary from the mission, create a situation where voters are exposed and . . . advantage the manipulations of state actors and local actors to impose barriers.” Holder still stammers in disbelief. “Okay, Mr. Chief Justice, you say that America has changed. OK. And what’s your basis for saying that, as opposed to Congress holding hearings, thousands of pages of testimony, hundreds of exhibits that say America has changed some, but not enough? You’re saying, ‘No, Congress, essentially you’re wrong.’ . . . OK. Then where were your researchers?” The former attorney general winces in horror when the case is referred to by its full name: Shelby County v Holder. He cites two days as the worst of his tenure: The day he accompanied President Barack Obama to console parents of children slain during the Sandy Hook massacre, and “the other one was to hear from the Supreme Court that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was, in substantial ways, murdered.” “Nothing had changed in the South,” he told me. “The only thing that changed was the personnel on the U.S. Supreme Court.” Verrilli also replays this crushing defeat in his head, wondering if there was anything he could have done to guard the Voting Rights Act against implacable foes. “I wish I could tell you, David, that I have stopped doing that, but I have not. It haunts me to this day.” He slows and wipes his eyes. It’s clear he is fighting back tears, unsuccessfully. “I think all the time about what I might have done differently, because it was a devastating defeat and it had huge consequences. I take solace in the thought that I don’t think there’s anything I could have done differently. But that only makes it marginally less powerful.” Adapted from Antidemoccratic: Inside the Far Right’s 50-Year Plot to Control American Elections by David Daley, Mariner Books, 2024. All rights reserved](https://www.thenation.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/RobertCrop.jpg)

On February 27, 2013, just a few hours after Solicitor General Donald Verrilli endeavored to protect the Voting Rights Act before the US Supreme Court, he dropped by his boss’s off…

David Daley

These are some concrete steps a President Harris could take to undo the damage of her current boss.

Gregg Gonsalves

As always, the DNC was an endurance grind. But my serendipitous encounter with a woman who embodies Harris’s reproductive justice agenda was the high point for me.

Joan Walsh

From district courts all the way up to the Supreme Court, judges are refusing to retire, holding on to power well past their prime.

Elie Mystal

[ad_2]