[ad_1]

![]()

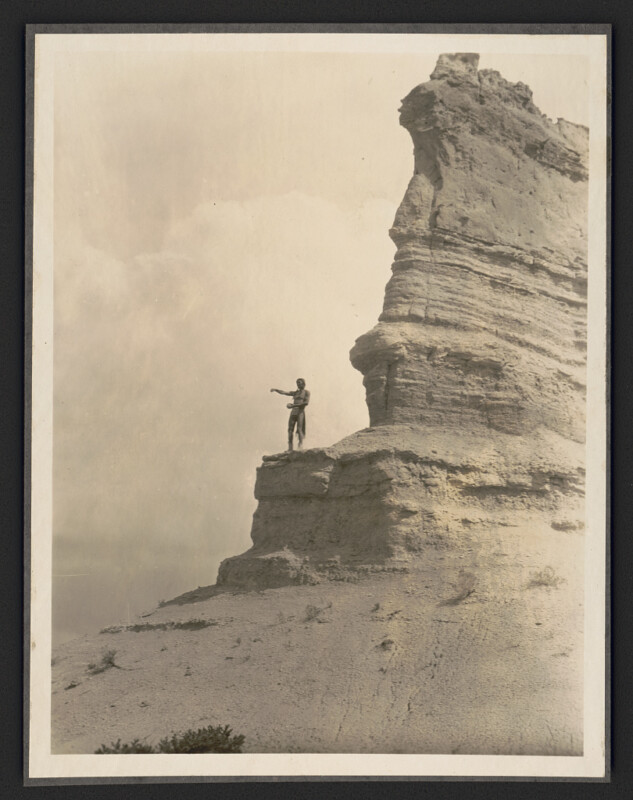

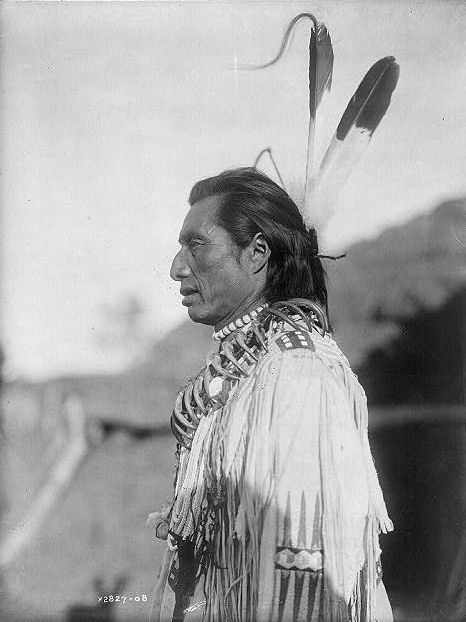

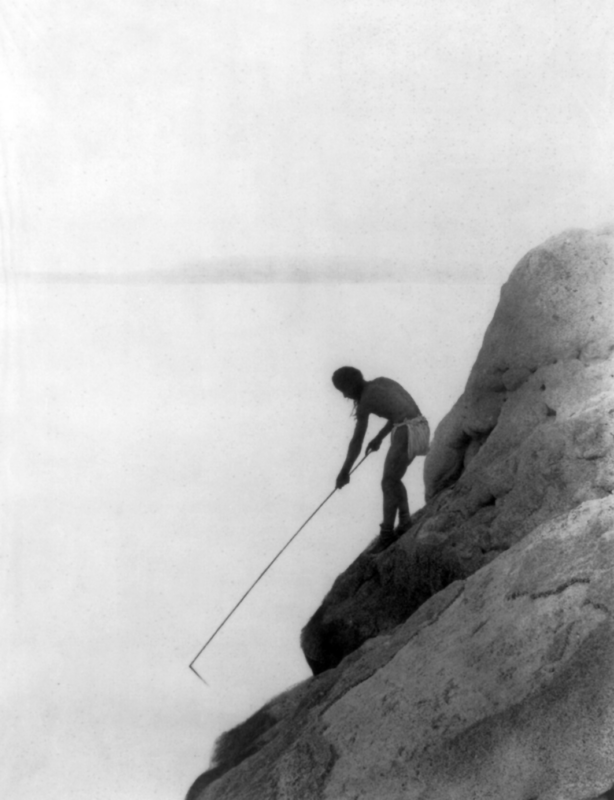

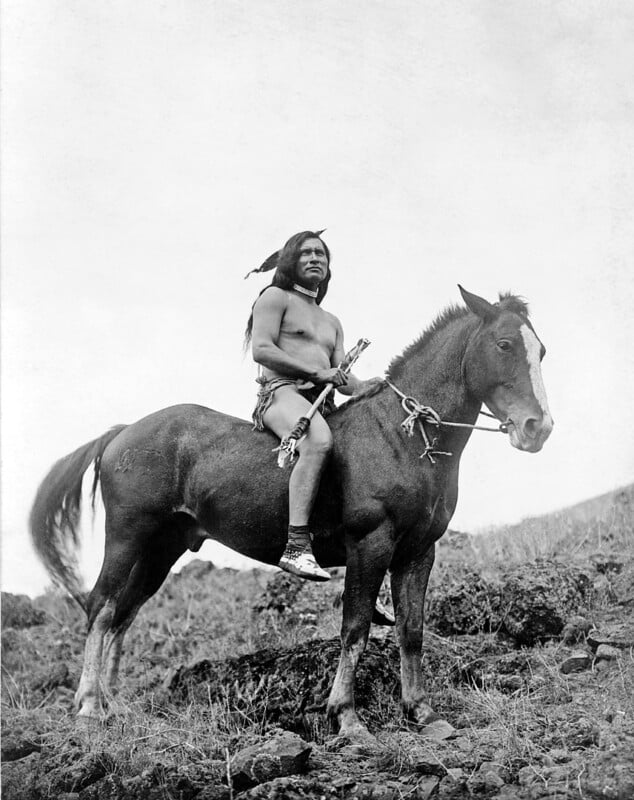

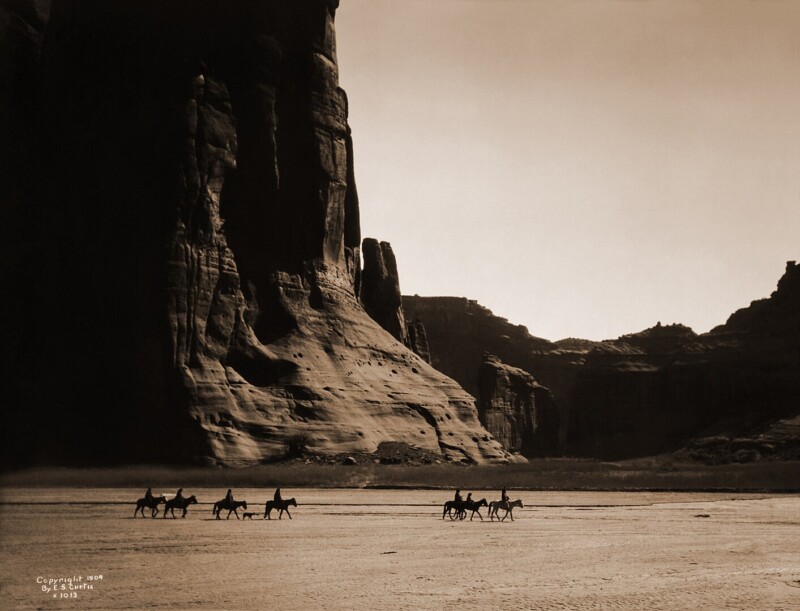

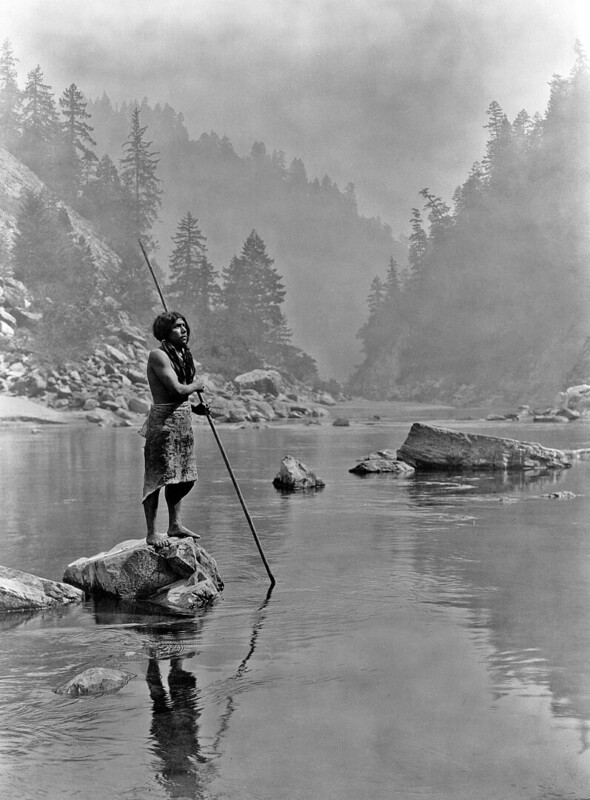

The work of an early 20th-century photographer who set out on a 30-year mission to document Native American tribes was almost forgotten about entirely until his work was rediscovered years later.

Born in 1868, Edward S. Curtis rose from humble beginnings in Whitewater, Wisconsin to become one of the most significant ethnographic photographers in history.

After establishing himself as a prominent portrait photographer in Seattle, his sliding doors moment came in 1900 when he photographed Princess Angeline, the daughter of Chief Seattle. This encounter sparked his profound interest in Native American cultures, leading to his ambitious project, The North American Indian.

Curtis embarked on this monumental journey with the intention of preserving a record of Native American life before it was irrevocably changed by modernization and forced assimilation policies. His work was supported by influential figures, including President Theodore Roosevelt and financier J.P. Morgan, the latter providing substantial funding that allowed Curtis to travel extensively across the United States.

The Library of Congress notes that like most scholars of this period, he believed that Indigenous communities would inevitably be absorbed into white society, losing their unique cultural identities. He wanted to create a scholarly and artistic work that would document the ceremonies, beliefs, customs, daily life, and leaders of these groups before they “vanished.”

Curtis utilized large format cameras, such as the 14×17 inch view camera, which produced highly detailed negatives. These cameras were cumbersome and required glass plate negatives which Curtis had to process in field conditions.

Additionally, he employed the photogravure process for his prints, a technique known for its rich tonal range and longevity, ensuring that his images would stand the test of time.

Over three decades, Curtis visited over 80 tribes, producing more than 40,000 photographs, 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of native languages and music, and extensive ethnographic notes. His magnum opus, The North American Indian, was published in 20 volumes between 1907 and 1930, each accompanied by a portfolio of large photogravure prints.

However, the book never sold well and the company that oversaw his work was liquidated and he sold the rights to J. P. Morgan Jr. The original glass plate negatives were forgotten about and many were destroyed.

Upon his death in 1952, Curtis’ work had faded into obscurity until it was rediscovered in the 1960s and 1970s. Since then, it has been recognized as an important record of Native American culture but not without controversy.

While he is lauded for his technical prowess and dedication, some critics argue that he staged scenes and paid people to fit in with his vision of a “vanishing race.” Despite this, his contributions remain invaluable, providing a visual and auditory archive of Native American cultures that might have otherwise been lost.

The Library of Congress acquired have one 1,000 prints of Curtis’ work and they can be viewed here.

[ad_2]