[ad_1]

For young people in Massachusetts facing queer- and transphobia, the statehouse feels very far away.

When Leslie moved to Natick, Massachusetts, an outer suburb of Boston, it seemed to her like an “extremely welcoming place.” There were rainbow flags everywhere; three-quarters of its voters went for Biden. When her child came out as nonbinary, they had a “pretty decent” time at their public school. Leslie (a pseudonym) wasn’t surprised: Massachusetts has long prided itself on being at the leading edge of LGBTQ equality. In 2003, it became the first state to legalize marriage equality, and over the past 15 years it has passed laws that prohibit discrimination against trans people and ban conversion therapy. As red and purple states have been consumed by fights over bathroom bans and gender-affirming care for minors, Massachusetts has charted a different course, enshrining the right to such care. In 2023, Maura Healey became the nation’s first openly lesbian governor in the country and declared the state a “safe haven” for the LGBTQ community.

But beneath the surface, a hard core of far-right activists are taking aim at the rights of LGBTQ kids in towns and school districts around the state, an inch-by-inch strategy that avoids statewide fights. Over the past four years, Tanya Neslusan, the executive director of MassEquality, a leading grassroots LGBTQ advocacy organization, has attended more than 60 school committee meetings and other events where anti-LGBTQ organizers were trying to make inroads. Neslusan has fought a ban on pride flags in Pembroke, a ban on drag events in North Brookfield, and extremist school committee candidates in Seekonk. Even unsuccessful anti-LGBTQ campaigns have an impact, Neslusan said: They can build name recognition for local candidates and desensitize people to extremist rhetoric, while provoking alarm among children and families who are already facing challenges. For kids facing queer- and transphobia in their communities, the statehouse can feel very far away. Neslusan thinks that conservatives are doing this not in spite of Massachusetts’s reputation as a safe haven but because of it. “If you get this information to catch on in Massachusetts, which is widely considered to be one of the more progressive states in the country,” they said, “you can get it to catch on anywhere.”

One of the key groups orchestrating the attacks is the Massachusetts Family Institute. Michael King, the organization’s acting CEO and director of community alliances, described it as a grassroots group. “Parental advocacy groups are just organically popping up,” he said. But the “non-partisan public policy organization,” as MFI calls itself on its website, is in fact deeply connected to national conservative groups. Founded in 1991, MFI is a designated state affiliate of the Family Research Council, the $24 million far-right organization that promotes conversion therapy and calls LGBTQ people pedophiles. MFI’s website also recommends resources for promoting religion in schools from “our friends at Alliance Defending Freedom,” the legal group known for bringing the case that overturned Roe v. Wade. When a middle-school student in Middleborough was prohibited from wearing a transphobic T-shirt, MFI teamed up with ADF to sue the district. As attacks on trans kids have become a central plank in Republican platforms, MFI’s budget has grown. For about 10 years, the organization’s revenues had hovered around $500,000 a year, but in 2021, its funding increased by 50 percent. The number of staff has doubled since 2020.

In 2023, as the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education prepared to release new health education standards recommending, for example, that students learn about gender identity, they received about 3,000 comments via e-mail during a public feedback period. Ninety-three percent of the comments were based on a script provided by MFI complaining that the standards would “teach students that they can change their gender.” The board ultimately adopted the new standards. But Massachusetts still has not passed the Healthy Youth Act, which would require that all schools teaching sex ed use curriculums that comport with those health education standards.

In Ludlow, a farm town turned suburb in western Massachusetts, the middle school agreed to remove a couple of library books containing sexual references in fall 2019. But when a parents’ group associated with MFI insisted that the school also remove a puberty-themed book (“about bodies, feelings, and YOU!”) the middle-school librarian, Jordan Funke, refused. The school’s policy was to evaluate the books before ditching them, and that process hadn’t happened yet. Besides, Funke was trying to create an inclusive environment for students—inviting them to provide their pronouns, for example—and the book contained valuable information about LGBTQ identity.

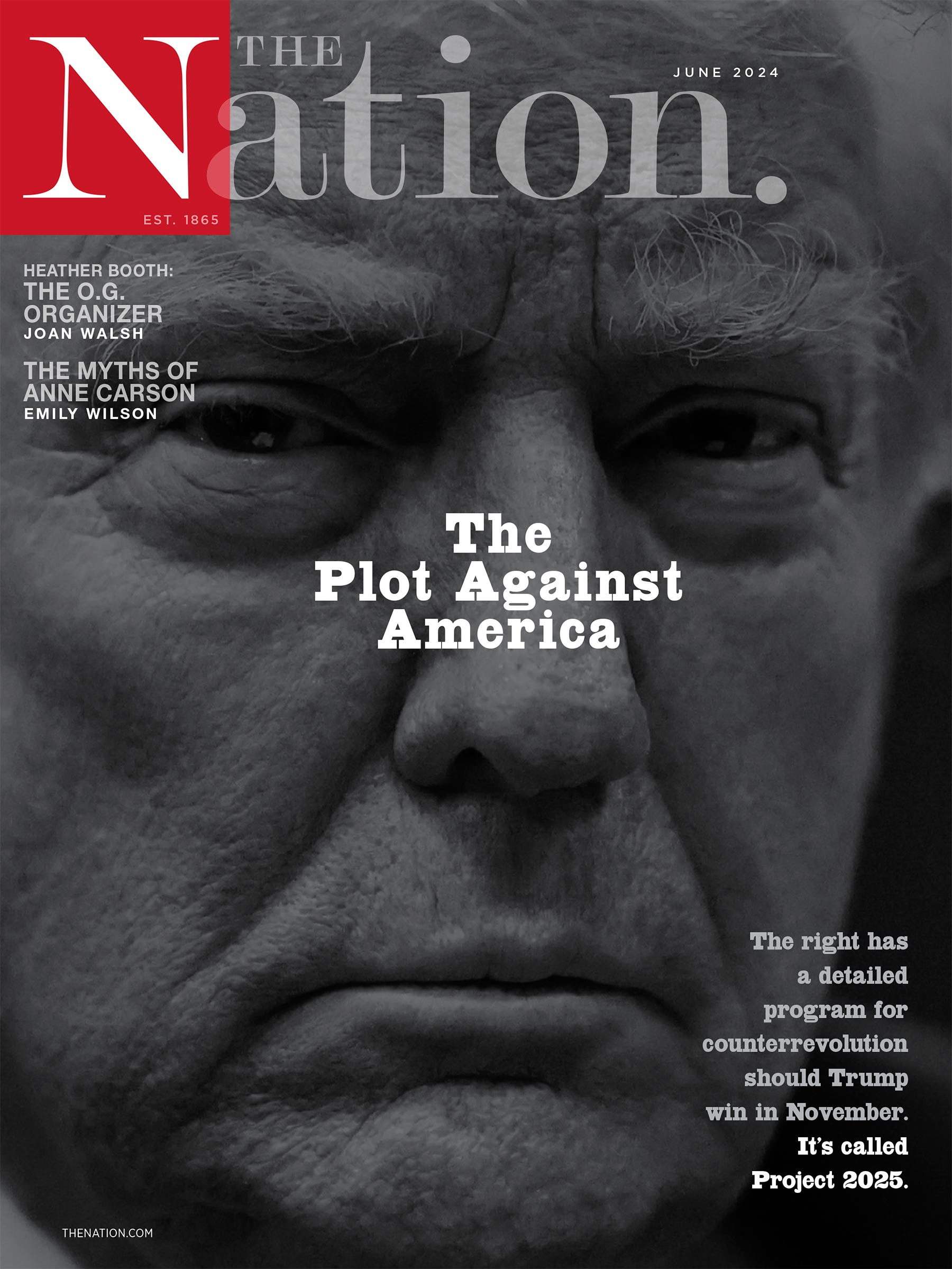

Appears In

That was a problem for some parents. It was also a problem for Funke’s colleagues. In November 2019, an educator named Bonnie Manchester spearheaded a letter from 19 fellow middle-school teachers accusing Funke of promoting “promiscuity” via library books. “These students are minors,” they wrote, “and we are there to protect them from sexual exploitation.” Funke, who is nonbinary, filed a complaint claiming that Manchester was targeting them for their perceived gender and sexual orientation.

Then, about a year into the pandemic, two siblings at the school came out as genderqueer and trans. Both asked that no one tell their parents right away, and the administration agreed: State guidance reminds schools that some trans students “are not openly so at home for reasons such as safety concerns or lack of acceptance.” Indeed, a counselor noted at the time, the elder “finds it hard to talk to [their] Dad sometimes because of the way he reacts.”

Bonnie Manchester told the students’ parents anyway, and without consulting either administrators or the students themselves. Livid, the parents joined the newly revitalized book-banning group, which reached out to an organization called MassResistance to distribute flyers around town (“Teachers and counselors are manipulating students to believe they can become opposite [sic] sex”). When the parents met with the Ludlow superintendent in April, they brought MassResistance president Brian Camenker with them.

Even by the standards of conservative activism, this was an escalation. Camenker, who founded his group in 1995 as the Parents’ Rights Coalition, has attended “straight pride” rallies alongside white nationalists, denied that gay people died in the Holocaust, compared advocates for LGBT youth to Nazi concentration camp guards, and linked homosexuality to pedophilia and bestiality. In 2010, the Southern Poverty Law Center named MassResistance as one of 18 groups comprising “the hard core of the anti-gay movement.”

Funke, the librarian, decided to quit that spring. But their ordeal wasn’t over. In a 13-part series on the MassResistance site, Camenker repeatedly referred to them as “a weird woman who dressed as a man” and accused them of indoctrinating students. And in April 2022, a lawsuit from the Massachusetts Family Institute arrived: The parents had filed a complaint against Funke, a school counselor, the principal, the former superintendent, the interim superintendent, and the school committee. Using their kids’ preferred names and pronouns, the plaintiffs argued, was a form of mental health treatment, and keeping the kids’ identities confidential interfered with the parents’ due-process rights to direct their upbringing. Among the more specific allegations: that the counselor called their younger child “brave and awesome” after they came out and that Funke had directed them to online resources about gender identity. The plaintiffs claimed that the latter constituted grooming.

The case was initially thrown out of court—calling someone what they want to be called isn’t health care, the judge said, and the state has broad authority to regulate education—but is now under appeal at the First Circuit.

Until recently, conservative groups “knew that anti-LGBT messaging was not popular,” said Megara Bell, the director of the Boston-based organization Partners in Sex Education. But over the past few years, it’s become more acceptable to target LGBTQ people more directly. “This is happening in so many communities, in so many states,” said Erica, another Natick parent who asked to use a pseudonym to protect her nonbinary child’s privacy. “There’s a playbook for it. There’s a blueprint to do it.” And it isn’t happening only in red states, or only in red towns and cities. The pandemic threw fuel on the fire. “All of a sudden there were a whole lot of people with time on their hands,” Bell said—time spent absorbing disinformation campaigns. On the Internet, Bell said, it was easy to find people to affirm your anger about masks in schools while introducing new lies about the education system: that teachers were “transing” your children, for example. If you cared about one issue, Bell said, the Internet would “radicalize you on every other issue.”

After her child’s coming out, Leslie was alarmed when parents at a middle-school council meeting in February 2023 began to complain about the school district’s DEI programs. Speakers at a PFLAG assembly had told students “to affirm, celebrate, and embrace” their peers rather than “follow their faith,” one parent, Pam Ahern, complained. By fall 2023, Ahern’s “group of moms” had become a 501(c)(4) organization, Parental Rights Natick—with the chair of the Republican Town Committee acting as treasurer. The group spent the winter promoting a school committee candidate named James Roberts, who proposed forcing schools to out gender-questioning students to their parents. Then, shortly before the election, the district received a 15-page letter from an out-of-state lawyer best known for his attempt to block the counting of electoral votes in the 2020 presidential election. The letter threatened legal action if the district did not change its policy protecting trans students’ confidentiality. Roberts’s campaign posted coyly on Facebook: “Cease and desist served?”

Roberts lost the election, garnering only 19 percent of the vote. But the community is still reeling. “When you dehumanize an entire group of people, that makes violence a lot easier,” said Erica. “We’re scared for our kids.”

And parents are scared for their public schools, too. During a candidate forum, Roberts echoed MFI talking points, claiming that faith communities had an important role to play in public schools. To combat antisemitism, schools should teach about Judaism, he said—but added that parents should be able to pull their kids out of those lessons, too. “Does that mean when the teachers are referring to my child as ‘they,’ that other child has to leave?” asked Erica. “Does that mean you can opt out when schools talk about evolution? Can you opt out when they start talking about how the world is round?” Such a policy, she said, would be impossible to implement.

But right-wing activists don’t have a problem setting public schools up to fail. As MFI has disparaged public schools as hotbeds of “indoctrination and sexualization,” it’s also pushed for the expansion of religious alternatives: homeschooling, church-based learning centers, and “biblically based schools.” The strategy is clear, said Megara Bell: Sex education—and LGBTQ inclusion—are being used as wedge issues “to undermine faith in public education, which then undermines funding for public education.”

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply-reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish everyday at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

Emmet Fraizer

Emmet Fraizer is a writer and fact-checker living in Brooklyn.

More from The Nation

The outcome is a win for abortion rights, but the court left open the possibility of future challenges to the FDA’s regulation of mifepristone.

Aziza Ahmed

The housing crisis is the logical outcome of real estate speculation and expanding unemployment—not an inevitable fact of life.

Class Notes

/

Adolph Reed Jr.

Many sports journalists are afraid to touch the issue of Palestine—but the stories are there waiting to be told.

Dave Zirin

Given Francis’s apparent embrace of LGBTQ people, many found his use of the offensive term frociaggine confounding—blame fragile masculinity.

Michael F. Pettinger

[ad_2]