The last time we used a scanning electron microscope (a SEM), it looked like something from a bad 1950s science fiction movie. These days SEMs, like the one at the IBM research center, look like computers with a big tank poised nearby. Interestingly, the SEM is so sensitive that it has to be in a quiet room to prevent sound from interfering with images.

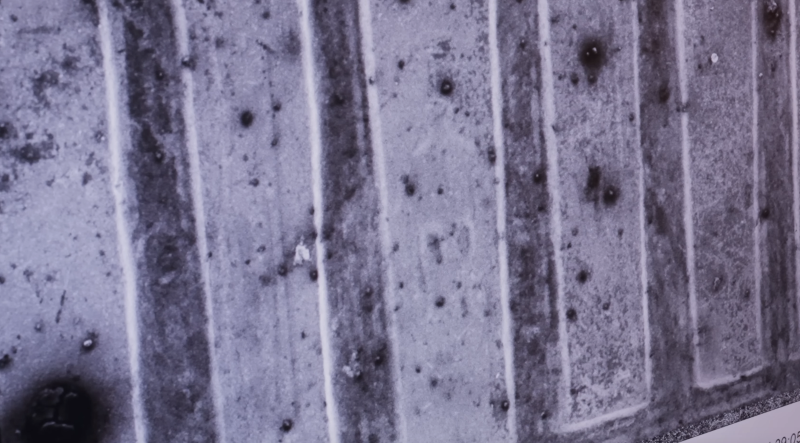

As a demo of the machine’s impressive capability, [John Ott] loads two US pennies, one facing up and one face down. [John] notes that Lincoln appears on both sides of the penny and then proves the assertion correct using moderate magnification under the electron beam.

Some electron microscopes pass electrons through thin samples much as light passes through a sample on a microscope slide. However, SEMs and REMs (reflection electron microscopes) use either secondary electron emission or reflected electrons from the surface of items like the penny.

You often see SEMs also fitted with EDS — energy dispersive X-ray spectrometers, sometimes called EDX — that can reveal the composition of a sample’s surface. There are other ways to examine surfaces, like auger spectrometers (pronounced like OJ), which can isolate thin films on surfaces. There’s also SIMS (secondary ion mass spectrometry) which mills bits of material away using an ion beam. and Rutherford backscattering spectrometry, which also uses an ion beam.

We keep waiting for someone to share plans to make a cheap, repeatable SEM. There are a few attempts out there, but we don’t see many in the wild. While the device is conceptually simple, you do need precise high voltages and high vacuums,. Also, you frequently need ancillary devices to do things like sputter gold in argon gas to coat nonconductive samples, so the barrier to entry is high.