[ad_1]

Skift Take

In recent decades, women have gone on to lead countries and major companies. But the airline industry has been much slower to close its broad gender gap across senior leadership, engineering, and pilot roles.

By Meghna Maharishi | June 6, 2024

“Are you a flight attendant?”

That’s the question Ashley Fields gets asked whenever she tells anyone she works in the airline industry. In fact, Fields is vice president of marketing and communications for Flair, a Canadian airline.

“I found it such an interesting reflection of maybe where aviation even sits as an industry in terms of the disparity,” Fields said. “And so I always like to say, ‘Well, why didn’t you ask if I was a captain or a pilot?’”

Fields is not the only woman in the airline industry to experience the ripple effects of a wide gender gap when it comes to roles like senior leadership, pilots and engineers.

When Joanna Geraghty became JetBlue’s CEO in February, she also became the first woman to lead a major U.S. airline in an industry that’s 110 years old.

During that time, women got the right to vote, joined the Supreme Court, got elected to Congress and went to space.

Around the world, women have become presidents and prime ministers of countries and CEOs of Fortune 500 companies. Other heavily male-dominated industries like financial services, automotive and consulting have appointed women to top executive spots.

But aviation has been much slower at closing that gender gap.

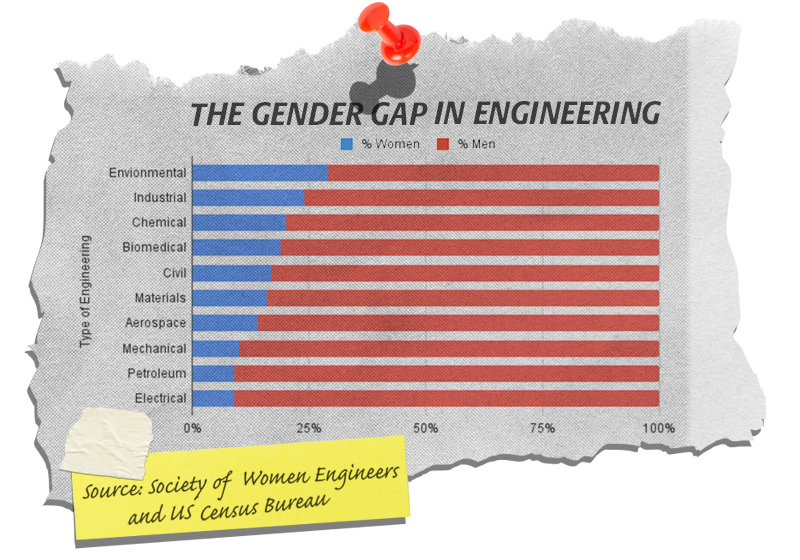

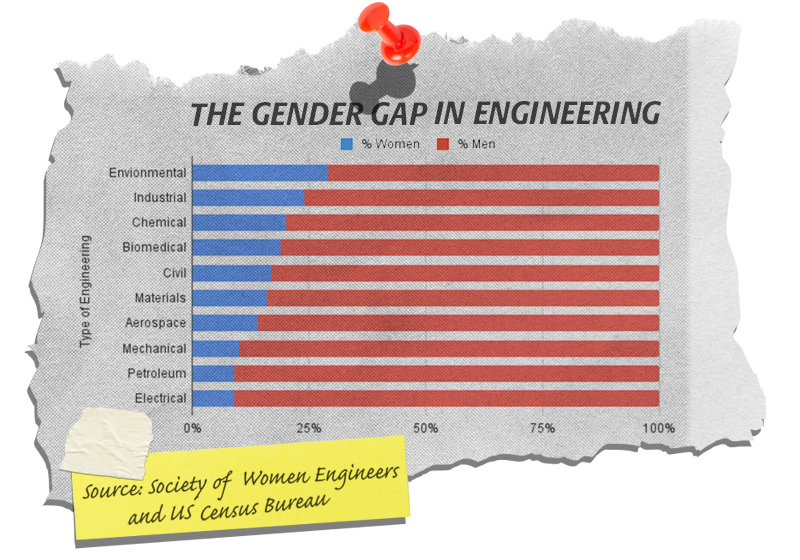

An Uneven Gender Gap

Despite glamorous flight attendants from the Golden Age of travel or the likes of Amelia Earhart or Bessie Coleman, the aviation industry has been dominated by men.

Here are the stats: Around 80% of flight attendants are women, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But among pilots, only around 8% are women. And that’s with a significant increase in the ranks of female pilots at commercial airlines in recent years.

The percentage of female captains is only 3.6%, according to a 2022 Women in Aviation Advisory Board report.

Measuring corporate roles in aviation is a bit more complicated. The BLS aggregates general corporate roles across industries, making it difficult to determine the full extent of the gender gap in the airline industry.

Similar to other industries, women tend to hit a ceiling. Based on the latest ESG reports from major U.S. airlines, women working in the corporate side were able to reach levels as high as director or managing director, but the number of women in vice president and C-suite roles then starts to taper.

At the most senior levels, United and Delta say women make up around 33% and 34% of those roles, respectively, according to their most recent ESG reports. And these percentages are either increasing or staying the same each year. For United, the number of women in senior leadership roles has stayed roughly the same for the past three years. In 2020, vice president roles were made up by 25% of women.

This gap widens at the C-suite. For example, at United, almost every executive with a C-suite title is a man. There were also two women with executive vice president titles, and Linda Jojo, the carrier’s chief customer officer, is the only woman to hold a “chief” title. At Delta, three of the 16 executives on the airline’s leadership committee are women.

The Women in Aviation Advisory Board report found that only 3% of CEOs of aviation organizations are women.

Yet the U.S. workforce is around 47% women, with 26% in STEM roles.

Europe has made a bit more progress in closing the gap. Airlines like Air France, KLM, Austrian Airlines, French Bee, and Aer Lingus are all helmed by women. Around 40% of employees in the European aviation industry are women, according to an EU report from 2023. The report found that women are most represented in the industry in flight attendant roles.

“The lack of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) has been a major factor for lesser women in the aviation sector,” the report read. “There is also a lack of knowledge about the requirements and the selection procedure for the aviation sector.”

Even then, the percentage of women in highly technical aviation roles is drastically lower. (Female pilots make up only 4% to 5% of the industry in Europe, for example).

A Pipeline Problem

The gender gap in aviation starts in childhood. Most young girls don’t grow up plane spotting. Toys are still heavily gender stereotyped. Boys have toy trucks and planes marketed to them whereas girls have dolls.

There’s not much improvement after childhood, either. Women are now outnumbering men in college. But aerospace engineering programs have some of the lowest percentages of women enrolled compared to other engineering fields.

Bill Crossley, the dean of Purdue University’s aerospace engineering program, said the issue lies in a lack of awareness.

“If you haven’t seen a woman space engineer or haven’t seen a woman pilot on the aviation side, how do you know that’s a career somebody could succeed at?” Crossley said.

It’s not just about gender. The aerospace and airline industries have had trouble attracting graduates, with the majority of those enrolled at elite schools opting to go in the tech, finance and healthcare industries.

At Purdue, the most popular engineering programs for female students are biomedical and environmental engineering — more than half of the students are women, Crossley said. But aerospace engineering only has around 18% female students, despite the fact that the student makeup at Purdue’s engineering school is around 50% women.

“We’re down near the bottom, which I don’t think is a good thing, but we’re down near the bottom along with mechanical and nuclear engineering,” Crossley said.

Crossley said he hopes the industry could fill its gender gap by recruiting more young women fresh out of school.

“[Airplanes make] the world smaller. We see people in Europe. We’ve visited Asia. I travel around the world for my job. I see how much more alike we are,” Crossley said. “And somehow that message doesn’t get across about aerospace engineering, maybe the way it does in biomedical engineering, where you’re working on a new device like a next-generation heart implant or providing artificial limbs for somebody.”

French Bee CEO Christine Ourmières-Widener said has had several instances in her career where a headhunter told her: “I’m not sure they’re ready for a woman.”

“I think that women really have to prove themselves, maybe, more than men have to,” she said. “Now that I’m a little bit more senior, more experienced with a number of experiences, it’s maybe less what I can face on a daily basis.”

A Marketing Issue

Despite the wide gender gap in certain roles like pilots or corporate ones, that doesn’t necessarily mean the industry is a difficult working environment for women. The overwhelming majority of women executives and pilots Skift spoke to said they’ve overall had positive experiences in the industry.

Juliana Ramirez, a vice president of ancillary revenue and digital at Flair, said she’s had several mentors invest in her throughout the course of her career.

“They have invested in me through paying for — for example, part of my tuition on my MBA, … allowing me to have a team earlier than probably I should have, believing in my ideas and coaching me,” Ramirez said.

Julie Rempel, the former director of marketing and communications at Canada Jetlines, said a director of airport operations helped her navigate the industry when she was starting out.

“He was really one of the biggest catalysts to helping me learn the industry from the ground up,” Rempel said, “and then after that you just continually fall in love with this aspect of how fast-paced it is and how exciting it can be.”

Still, the issue really starts with the fact that most women aren’t even aware of the career paths in the aviation industry beyond pilots and flight attendants.

“Depending on which research you read, boys will generally decide they want to be in aviation by the age of six and girls at 16,” said Jane Hoskisson, the International Air Transport Association’s director of talent, learning and diversity. “That’s a 10-year age gap where every decision that they move towards helps them into that industry whereas girls are playing catch up right from the start.”

And for all the good experiences in the industry, airlines have also come under criticism in the past for their attempts to fix the gender gap. At an IATA conference in 2018, a panel of executives discussed ways to recruit more women. The only issue was that the panel solely featured men.

Former Qatar Airways CEO Akbar Al Baker, when asked at a 2018 news conference about the lack of women in the industry, infamously, said: “Of course it has to be led by a man, because it is a very challenging position.” Qatar tried to walk back Al Baker’s controversial comments, but it reflected a mindset that women couldn’t handle the job.

Ourmières-Widener said the industry still has a long way to go in evening out the gender gap. She suggested that the industry needs to better communicate careers in aviation to young women while they’re in school.

“The difficulty we have is not that we don’t want to recruit or are not ready to recruit,” she said. “When I see the recruitment we have now in the two airlines we have in the group, we have difficulties to recruit female pilots and female engineers because the number of candidates we have is definitely biased — you have a huge percentage of men.”

Recruitment Pushes

The industry has been trying to make big pushes to recruit and promote more women.

For example, SkyTeam started an initiative called “RISE,” which is currently focused on increasing the number of women in senior leadership roles. Evegenia Starkova, the head of marketing and sustainability at SkyTeam, said the program trains women in soft skills and points out possible paths for development.

Starkova said the team found that women sometimes struggle to reach senior roles due to a lack of exposure to opportunities and mentorship.

“We know that exposure is important, but also quite not easy, but it’s possible to improve that,” Starkova said.

The biggest initiative to close the gender gap is IATA’s 25by2025 campaign that seeks to increase the number of women in senior or underrepresented positions by 25% in the next year or so.

Hoskisson, the director of talent, learning and diversity at IATA, said 20by2025 started in 2019 at IATA’s annual conference.

“What could you do in five years? Well, you could actually improve your metrics,” Hoskisson said. “You could measure the improvement in your metrics. You could either improve them by 25% from where you currently are, or you could get to 25%.”

Since then, over 200 airlines and other aviation companies have signed on to IATA’s 20by2025. In the U.S., American, Delta, Hawaiian, JetBlue and United have signed the pledge.

Senior leadership among participants increased from 19% to 28%. Those airlines have also increased the number of female pilots by 1,000.

As a result of the project, some airlines are reaching out to schools and encouraging more women to pursue an education in STEM. For example, 8% of engineers at Royal Air Maroc are now women —up from zero — after partnering with local universities.

“There’s not one perfect solution, but lots of airlines are experimenting and trying to do different things to make it as attractive as possible,” Hoskisson said.

Motherhood and the C-Suite

Perhaps one of the most difficult issues for women who work in the airline industry — whether they’re a vice president or a flight attendant — is balancing motherhood with a demanding job.

Rempel said she felt as if she had to keep quiet about being a mother.

“Whether it was true or not, I had this overarching feeling that being a mom or having responsibilities at home was a negative,” she said. “I had to be careful with how much I divulged with the balancing act of home and life and work.”

Julia Haywood, the former chief commercial officer of United Airlines, said it can be difficult balancing having children and working a C-suite role since it can feel like a 24/7 job.

“At the C-suite level, it is all of you. It is 150% of who you are, at a big airline anyways,” Haywood said. “A lot of women choose that they want to do both. From my experience, I’ve been asked many times to take on roles that are going to be 24/7, I’ve said no because I don’t want that in my life right now.”

It’s not just women in the airline industry that struggle with balancing the demand of motherhood with their jobs.

That feeling of needing to choose between a career and kids is part of a phenomenon called the “motherhood penalty.” Shelley Correll, a sociologist at Stanford University, found that mothers typically earn less than men in the workplace and can sometimes face the perception that they aren’t as committed to a job because they have children.

And sometimes a job can come first. Mahalia Wreggitt, a pilot at Flair, said she and her husband, who is also a pilot, have put off having children due to their demanding schedules.

“There are some barriers that I find, like I want to have a family, but it’s very difficult when I can barely schedule an interview with you because I’m getting called on to the road last-minute,” Wreggitt said.

Some female executives said they strive to be more mindful of accommodating moms in the workforce.

“As a manager of females and males that have children, it is my philosophy that I can only be as good as my employees are happy,” Fields said. “And so it is my prerogative that they feel like they have that work-life balance. I think that that is so critical.”

Haywood said as a new mom, she would want to recruit more mothers into corporate roles in the industry.

“As a mom I now know and would recruit mothers,” she said. “Women can bring so much more to the table and it’s like now as a mother, I can see time management, balancing multiple things.”

It’s All About Mindset

For the women that have gone on to have successful careers in aviation, many of them said they don’t tend to focus too much on the obstacles.

Karen Feaster, the director of Florida’s Daytona Beach International Airport, said growing up near Boston Logan International Airport led to a lifelong affinity for aviation, and a career where she rose the ranks of the Florida airport.

“It’s all about your integrity making sure you stay true to yourself and the industry,” Feaster said.

Ramirez said she felt as if she was raised as boy in Mexico before starting her career at Flair, with the way her parents encouraged her to pursue an education.

“I always saw myself in the mirror as a winner and that helped me select good companies and select good leaders,” Ramirez said.

Heather Figallo, the chief transformation officer of low-cost Spanish airline Vueling, said she never stopped herself from pursuing an opportunity because of her gender.

She started her career in the airline industry working with American Airlines on its strategy when it filed for bankruptcy in 2011 and merged with U.S. Airways. Figallo then took a job at Southwest Airlines, working in product innovation and customer experience roles before moving to Spain.

“There’s a leadership job or there’s a job in that area. Somebody has to have that job, why not me? I’m qualified, I’m smart, I work hard,” Figallo said. “And so I understand that people have those feelings, but for me personally, I never had those feelings. And I think that’s part of the reason why I’ve been able to progress and get into senior leadership in what has historically been a male-dominated industry.”

Meghna Maharishi is Skift’s Airline Reporter. Contact her at [email protected]

Graphics by Taylor Slattery

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

[ad_2]