[ad_1]

Growing up in the Grays Ferry neighborhood of South Philadelphia, Shawmar Pitts never thought twice about the oil refinery looming in the background, spewing toxic fumes in plain sight. It wasn’t until years later that he finally made the connection between the refinery and exposure to chemicals that put his community at high risk for life-threatening diseases.

“Every single house, somebody has asthma, somebody has cancer, somebody has those heart diseases and lung diseases that’s caused by these contaminants from the oil refinery,” Pitts said. “All this time, we were wondering why people are getting sick, and the oil refinery is the culprit.”

The Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery complex, founded in the 1860s, was once the largest oil refinery on the East Coast, emitting carcinogenic chemicals into South and Southwest Philadelphia for over a century before multiple explosions in 2019 finally brought it to a permanent close. The effects of the refinery’s sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, and particulate matter emissions have left a lasting impact on the health of those living in the majority-Black, working-class neighborhoods directly adjacent to it. This is in keeping with the findings of a 2017 report from the NAACP and Clean Air Task Force that found that Black people are 75 percent more likely to live next to polluting sites, such as oil refineries, than white people.

In the book Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility, scholar Dorceta Taylor writes that communities of color, particularly Black communities, were corralled into poor neighborhoods through processes of racial segregation. Even more, Taylor explains that industry seeks out these neighborhoods to set up shop: neighborhoods with low educational attainment, high unemployment, and low community organization engagement—places with little agency to resist environmental hazards.

“Our schools were the worst schools in Philadelphia when it came to standardized test scores,” Pitts said. Meanwhile, the oil refinery made millions—none of which, Pitts says, was meaningfully invested in the surrounding community.” Universal Audenried Charter High School—formerly Charles Y. Audenried High School—which serves Grays Ferry, still performs well below the state average, achieving 38 percent proficiency in reading and 10 percent proficiency in science.

It’s this reality that informs Pitts and his organization Philly Thrive’s dedication to making sure that fence-line communities in South and Southwest Philadelphia—like Grays Ferry—will benefit from new development on the refinery site.

Philadelphia shows that the fight for environmental justice hardly ends once a refinery is shut down. Decades of pollution have not only harmed the health of residents but also contaminated soil and bodies of water. How can people guarantee that their communities will be cleaned up? What will happen to all the jobs the oil refinery provided? And how can people ensure that the prosperity promised by a new development will not push residents out of the neighborhoods they have lived in for decades?

Alexa Ross moved to Philadelphia in 2014 after graduating from Swarthmore, a liberal arts college on the outskirts of the city. Originally from Nebraska, Ross was involved in climate organizing as anuundergraduate, but wasn’t aware of Philadelphia Energy Solutions until she came across its expansion plan. “We realized that there was this massive oil refinery and no one’s talking about it, and it was right under our noses as climate activists,” Ross said.

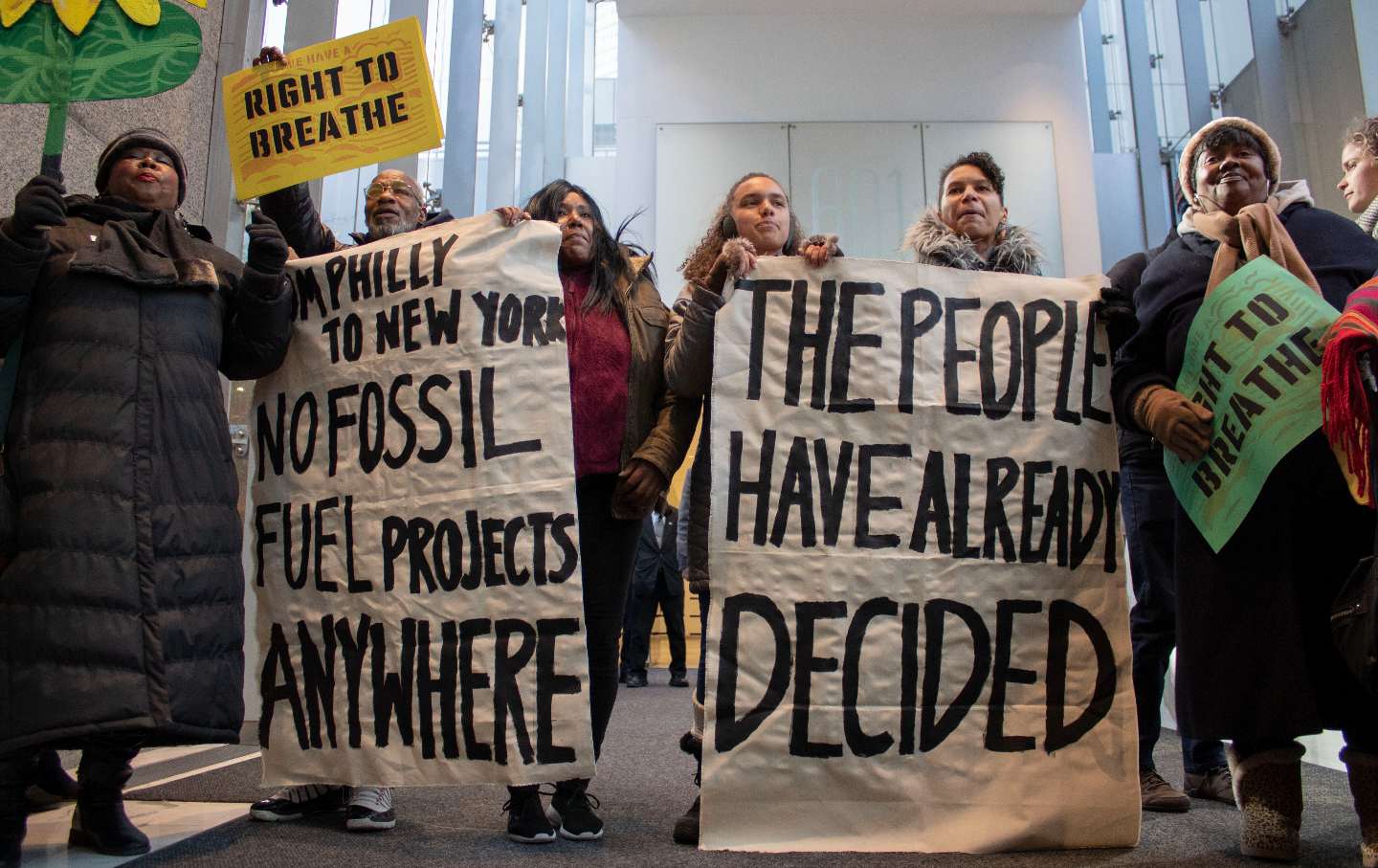

Ross began door-knocking in neighborhoods around the refinery, telling residents about the expansion. Ross, a white woman, knew that building trust would not be easy. But she wanted to help create a movement where fence-line communities could be at the forefront. Going door to door, she found that residents—fed up from experiencing decades of health consequences—were ready to lead. From many different efforts like hers, Philly Thrive was born. Soon after, the organization kick-started its “Right to Breathe” campaign building momentum to shut the refinery down. Then, in June 2019, the explosions happened.

According to the Federal Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, the incident was caused by a worn-down piece of pipe, long overdue for replacement—causing a spill of dangerously combustible hydrocarbons among other chemicals, releasing over 3,000 pounds of deadly hydrofluoric acid into the atmosphere.

After the incident in 2019, Philadelphia Energy Solutions filed for bankruptcy and went up for sale. At first, local politicians and the Trump administration tried to keep the refinery open—or at least ensure that another oil project could take over the site. The United Steelworkers Union, citing a loss of jobs, staunchly opposed the refinery’s closure.

But Philly Thrive made it their mission to ensure that the next buyer would not be an oil company. Protesters showed up at bankruptcy court, lying limp on the courtroom floor to show how the refinery killed members of their community—all in an effort to ensure that Hilco Redevelopment Partners, a real estate company that specializes in redeveloping former industrial sites, and the only non-refinery seeking to buy the site, would succeed in winning the bid.

In 2020, Hilco bought the site for $225 million, vowing to transform it into The Bellwether District, “a 1300-acre state-of-the-art campus for e-commerce, logistics, life science and innovation leaders.” But first, the company needs to clean up, or remediate, the area: a complicated, decade-long process of removing lead and organic chemical contamination from an extremely large and heavily polluted site.

The remediation of the former refinery site is a joint effort by Hilco and Sunoco, which previously owned the property. Hilco’s remediation strategy has involved vapor extraction in areas of deep soil contamination, while elevated soil contamination is addressed through excavation and off-site disposal. Areas unfit for in-place treatment have been targeted with soil caps (which places covers, such as concrete, over contaminated soil) alongside vapor intrusion mitigation systems and restrictions on future use. As of June, the company has removed 18.5 million gallons of petroleum product, 344 aboveground tanks, and 137,000 feet of pipeline, while also recycling 190,000 tons of metal.

According to Alain Plante, professor of Earth and environmental sciences at the University of Pennsylvania, it’s important to understand that a former refinery site—especially one as big as Philadelphia Energy Solutions—cannot be remediated to “zero.” Instead, there are acceptable remediation standards set by the state or federal government based on the site’s history. For example, when Hilco bought the refinery, it was required to remediate only to a “refinery standard,” which still leaves a relatively high level of lead and organic chemicals in the site.

Hilco, to its credit, opted to remediate to a higher standard, working with the EPA to reach a “commercial level.” Still, community members have expressed concerns over this strategy. Philly Thrive, in particular, is concerned about soil capping, especially with regard to the fact that the site and some of its neighboring communities sit on 100- and 500-year floodplains.

According to Erik D. Olson, senior strategic director for health at the Natural Resources Defense Council, although capping the site can in some cases delay or reduce the movement of contaminated water, it “rarely completely stops the movement of that water either offsite or from discharging into nearby waterways” and that flooding can damage caps.

Hilco conducted a two-year flood study with FEMA to ensure that the redevelopment plan will have a minimal impact on flooding. Yet there was no evidence of the company directly consulting with local community groups in either their flood mitigation or remediation strategies, while regulatory agencies, who were consulted, like FEMA don’t have good environmental justice track records, especially when it comes to flooding. “The cleanup should be planned and executed in close collaboration with the community; USEPA should carefully monitor whether the state is ensuring this,” Olson said.

Hilco says that it has brought local Philadelphians onto its team, including a community engagement lead who is a South Philly native, yet the extent to which community groups have been meaningfully involved in the company’s decision-making processes remains questionable. Philly Thrive feels that Hilco’s community engagement looks a lot more like communicating what it is going to do, rather than collaborating and coming to a decision on their next steps together.

Ad Policy

Walking around Grays Ferry today, one can already see a transformation. Three-story luxury developments line blocks formerly occupied by two-story rowhomes. Homeowning residents say that they have been approached by investors pressuring them to sell.

According to the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia, between 2016 and 2021, most neighborhoods in South Philadelphia—including Grays Ferry—saw a decline in residential populations. Moreover, between 2017 and 2018, over a quarter of residential sales in Grays Ferry were going to buyers listed under LLCs, a common precursor to higher rents and property taxes. In 2018, the median price of a single family home in Grays Ferry was $100,000—nearly triple the median price from five years before.

Lance Freeman, professor of city and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania, says that the ongoing gentrification in South Philadelphia has been a result of the expansion of University City—where Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania are located—as well as the growth of Philadelphia’s educational and health industries. Freeman echoed concerns that Hilco’s new Bellwether District could expedite gentrification, as it attracts high-income people to the area.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Hilco demurs. “Beyond the fact that we’re not going to be directly contributing to additional housing being built in the neighborhood, I think it’s a real misconception to characterize the jobs in our site as being elite or jobs that are not available to local community members,” said Amelia Chasse Alcivar, executive vice president of corporate affairs for Hilco. “We’re projected to create 19,000 permanent jobs on the site and those will run from jobs that you don’t need a high school degree for to jobs that are, yes, going to PhDs and everything in between.”

Freeman notes that the inclusion of jobs for people without a college education is a good step, but it does not mitigate the company’s contribution to displacement. Additional mechanisms should be put in place to buffer the negative effects of gentrification, such as more affordable-housing options, he said. “Sometimes people might also feel pushed out because the character of the neighborhood is changing,” Freeman added. “For that, you need to solicit community input into the redevelopment process, so that people who live in the neighborhood can feel like they have had some say.”

Hilco says that one of its goals is workforce development and ensuring that residents won’t be displaced. According to Chasse Alcivar, initiatives to ensure these outcomes will be an ongoing discussion with residents throughout a community benefits process.

For communities in South and Southwest Philadelphia, the question of how residents can ensure proper site cleanup and the implementation of anti-displacement mechanisms boils down to a community benefits agreement with Hilco: a legal contract between local residents and developers that outlines how a new project will benefit community members.

Community benefits agreements can accomplish different things from funding residential projects to environmental regulations. However, the concept of these agreements is still new. The first community benefits agreement was signed in Los Angeles in 2001, when the then–Staples Center was looking to expand.

“The one city that I know of that passed a community benefits ordinance in 2016 was Detroit,” said Nicholas Robinson, professor of political science at Otterbein University. “But many other cities have attempted to draft legislation. They’re sort of floating under the bubble of various city councils across the country.” In Philadelphia, a 2019 bill that would have required community benefits agreements for select “high-impact developments” receiving city financing was vetoed.

“It’s a voluntary community benefits agreement,” Chasse Alcivar said. “We’re not doing it because we have to, but because we want to.” (While participation in the CBA is Hilco’s choice, once an agreement is negotiated it becomes legally binding.) Moreover, according to Chasse Alcivar, Hilco has already committed to ongoing financial pledges to fund education and job opportunities, an internship program, a partnership with the Salvation Army for Thanksgiving turkey and coat drives, and a fund for tree plantings, among dozens of other projects. But without the teeth of a legal contract to hold Hilco accountable these commitments are just “philanthropic activities,” according to Robinson.

While Hilco said it was open to community benefits, it wasn’t until September 2022—two years after acquiring the site—that the company publicly committed to going through with an agreement.

Since 2021, a coalition of community groups under “United South/Southwest Coalition for Healthy Communities” has been advocating for a formal community benefits process, and Hilco has obliged. Currently, the company is negotiating an agreement with their Community Advisory Panel (CAP), consisting of about 25 groups led by council president Kenyatta Johnson, including the United South/Southwest Coalition.

While Philly Thrive was initially a part of the coalition, it later dropped out, telling WHYY Radio it left in order to continue staging direct actions to protest parts of Hilco’s ongoing redevelopment “without constraints,” while helping ensure that the rest of the coalition maintains a seat at the table. Philly Thrive has continued to criticize the efficacy of an agreement being negotiated by a panel the company handpicked and criticizing a lack of transparency and the start of construction before a formal agreement has been reached.

“Philly Thrive isn’t the only community group in the neighborhood, and there’s a variety of different neighborhoods that are a part of this process that are at table, providing input and getting their issues and concerns addressed as it relates to the Hilco Bellwether District,” council president Johnson said. “My sentiment is that it’s been an inclusive process thus far, it’s been a transparent process thus far.” Johnson said that no other individuals have expressed concern with the company building without the resolution of a community benefits agreement.

While activists and Hilco were once aligned in the mission to remove fossil fuel interests from South and Southwest Philadelphia, the sentiment from local politicians now is that Philly Thrive is a rogue actor without community roots—an organization that is alone in pushing the narrative that Hilco is a bad actor.

Certainly not every organization feels the same way about what Hilco should prioritize and how a CBA process should be conducted. Donna Henry, executive director of the Southwest Community Development Corporation, a CAP organization, is not concerned about Hilco building before a community benefits agreement, but raised concerns about how much money the company has to designate toward community investment projects. The organization hopes to see Hilco prioritize sustainable jobs and workforce development.

A major issue when it comes to community benefits, Robinson says, is figuring out how to include all “relevant” voices. Romany Webb, deputy director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School, adds that developers often shy away from negotiating with newer organizations, as it can be harder to guarantee whether they will have the longevity to enforce an agreement. Concerns around Philly Thrive, however, seem to revolve more around what “narrative” the group has pushed, rather than how old it is. “Everything that Philly Thrive has [said], I’m concerned about,” said Charles Reeves, executive director of another CAP organization. “I want to make sure the jobs go to the right people. I want to make sure they clean it up right. I want to make sure with the gentrification that they help us with housing.” Reeves’s priority is that Hilco focus on neighborhoods most impacted by the refinery: Wilson Park, Bartram Village, Eastwick, Passyunk, and Grays Ferry.

“One of the biggest critiques of community benefits agreement is that developers, particularly if there’s no legislation concerning whom they have to negotiate, can pick and choose who they want to negotiate with,” Robinson said. “You can understand why a developer would have a strong interest in sidelining a group that is really concerned about climate change or environmental destruction. Those groups with the most challenging criticisms are the ones that present the biggest problems for developers.”

“We need to have meaningful public policy that puts into place directives for how economic development happens and that then provides a secure, stable, and just grounding community benefits agreements,” said Dr. Giovanna Di Chiro, who teaches environmental justice theory at Swarthmore. “Cities and their residents should be driving what kinds of futures they want.”

Reeves says that frontline communities should have guided Hilco’s development from the beginning. But now that that point has passed, his priority is to formalize a contract as soon as possible. “Philly Thrive, they my neighbors, they my friends, we grew up together,” Reeves said. “They have the same concerns. I’ve been dealing with Hilco for four years. It’s time to bring Hilco to the table. Let’s get this done.”

We need your support

What’s at stake this November is the future of our democracy. Yet Nation readers know the fight for justice, equity, and peace doesn’t stop in November. Change doesn’t happen overnight. We need sustained, fearless journalism to advocate for bold ideas, expose corruption, defend our democracy, secure our bodily rights, promote peace, and protect the environment.

This month, we’re calling on you to give a monthly donation to support The Nation’s independent journalism. If you’ve read this far, I know you value our journalism that speaks truth to power in a way corporate-owned media never can. The most effective way to support The Nation is by becoming a monthly donor; this will provide us with a reliable funding base.

In the coming months, our writers will be working to bring you what you need to know—from John Nichols on the election, Elie Mystal on justice and injustice, Chris Lehmann’s reporting from inside the beltway, Joan Walsh with insightful political analysis, Jeet Heer’s crackling wit, and Amy Littlefield on the front lines of the fight for abortion access. For as little as $10 a month, you can empower our dedicated writers, editors, and fact checkers to report deeply on the most critical issues of our day.

Set up a monthly recurring donation today and join the committed community of readers who make our journalism possible for the long haul. For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth and justice—can you help us thrive for 160 more?

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

Amber X. Chen

Amber X. Chen is a 2024 Puffin student writing fellow focusing on climate change for The Nation. She is a sophomore at UC Berkeley. Her writing has also appeared in The Guardian, Atmos Magazine, Los Angeles Public Press, Teen Vogue, the Los Angeles Times, and The Philadelphia Inquirer.

More from The Nation

In 2019, Harris said that there was “no question” that she would pursue a federal ban on fracking. In 2024, she’s taken a different—and unnecessary—stance.

Amber X. Chen

With additional funding, the Tennessee Valley Authority could provide union jobs, kick-start American industrial production, and help the world go green.

Fred Stafford

Hotter temperatures can increase aggressive behaviors, making violence more likely during the accelerating climate crisis.

Ilana Cohen and Thea Sebastian

An interview with Alice Hu, one of the lead organizers of the “Summer of Heat” campaign targeting Wall Street fossil fuel financiers.

Wen Stephenson

[ad_2]