[ad_1]

(RNS) — This week, the Louisiana Legislature passed a bill requiring the Ten Commandments to be posted in every public and charter school classroom in the state. Once signed, as expected, by Republican Gov. Jeff Landry, the statute will, of course, be challenged in court.

We’ve been here before.

Forty-four years ago, the Supreme Court summarily reversed a lower court’s decision that a virtually identical Kentucky law was constitutional because its “avowed purpose” was “secular and not religious.” In fact, declared the court’s per curiam (unsigned) opinion in Stone v. Graham, “(t)he pre-eminent purpose for posting the Ten Commandments on schoolroom walls is plainly religious in nature.”

Like their Kentucky predecessors, the solons of Louisiana contend that their display will serve not to inculcate religion (God forbid!), but to make students aware that “(r)ecognizing the historical role of the Ten Commandments accords with our nation’s history and faithfully reflects the understanding of the founders of our nation with respect to the necessity of civic morality to a functional self-government.” As in, I suppose:

What’s adultery, Miss Jones?

It’s when you have sex with someone other than the person you’re married to, Johnny.

You mean like President Trump with Stormy Daniels?

I guess so. Now can we get back to Alexander Hamilton?

But I digress.

The Louisiana bill ignores Stone v. Graham, citing instead Van Orden v. Perry, a 2005 decision that permitted retention of a monument inscribed with the Ten Commandments at the Texas State Capitol. There, the crucial fifth vote came from Justice Stephen Breyer, who argued in a concurrence that the monument had been in place uncontested for a long time and could be construed as essentially secular in purpose.

“The display is not on the grounds of a public school, where, given the impressionability of the young, government must exercise particular care in separating church and state,” Breyer wrote.

Significantly, on the same day that the Van Orden decision came down, Breyer made up the majority in another 5-4 decision, McCreary v. ACLU, which determined that two Kentucky counties’ decision to post the Ten Commandments in their courthouses did violate the establishment clause — not that the Louisiana Legislature took note of this.

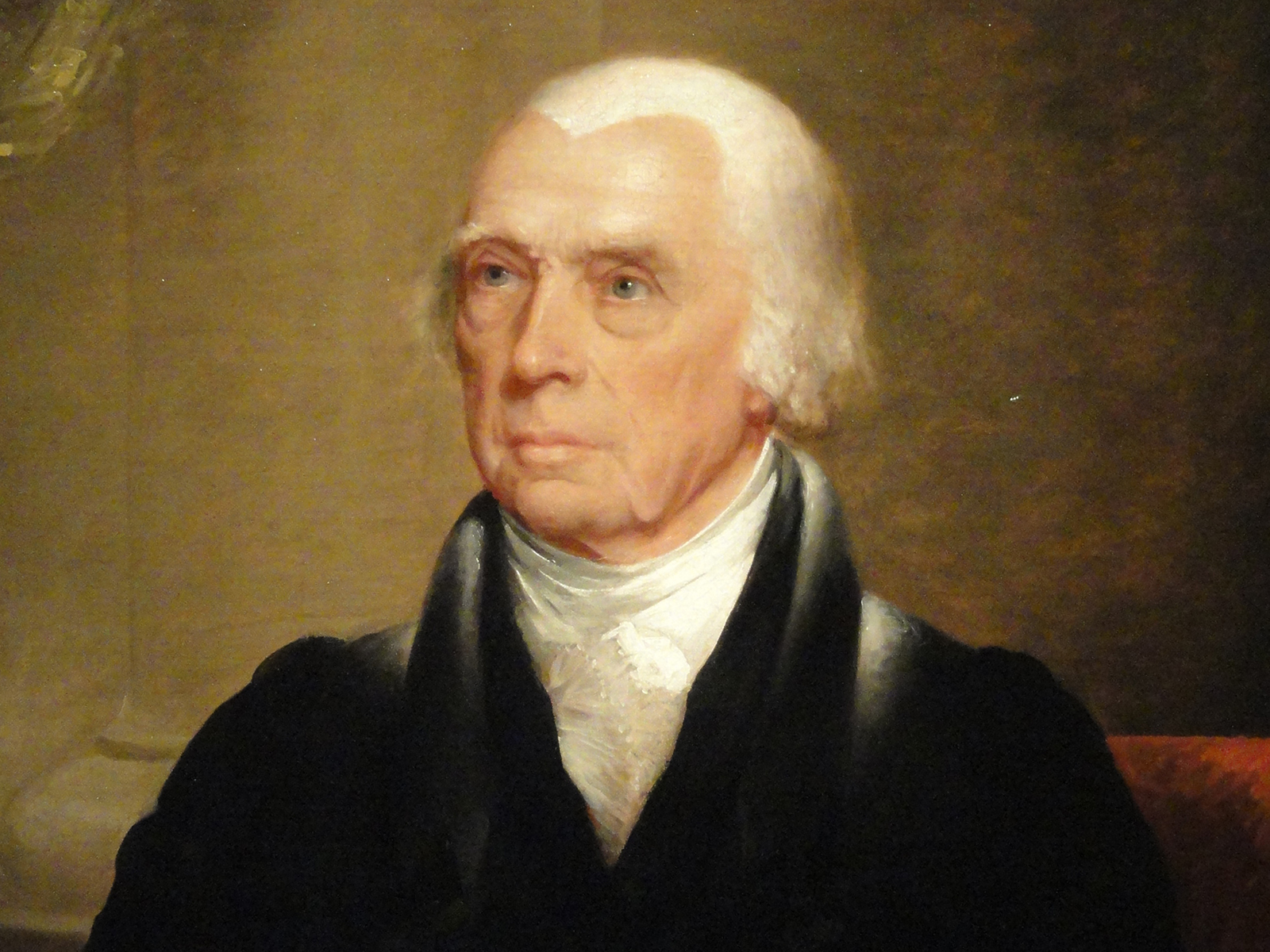

As to the understanding of the founders of our nation, the Louisiana bill buttresses its position by invoking the support of the founder known as the Father of the Constitution: “History records that James Madison, the fourth President of the United States of America, stated that ‘(w)e have staked the whole future of our new nation … upon the capacity of each of ourselves to govern ourselves according to the moral principles of the Ten Commandments.’”

Actually, history records no such thing. The quote is a slight variation on a hoax concocted by the evangelical pseudo-historian David Barton in his 1992 book, “The Myth of Separation.” Barton has made a career of persuading fellow evangelicals that founders like Madison and Thomas Jefferson did not believe in the separation of church and state.

That’s notwithstanding Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptists, which asserts that in approving the establishment clause the country had built “a wall of separation between Church & State.” If Jefferson was a bit metaphorical, Madison — who oversaw the drafting of the establishment clause as chair of the conference committee that created the Bill of Rights — was explicit.

In a letter in 1819, he praised Virginia’s approach — which he had engineered in 1786 — as “the total separation of the Church from State.” He likewise used separationist language to describe the federal arrangement but worried about efforts to undermine it.

As he wrote in a memorandum after his presidency: “Strongly guarded as is the separation between Religion & Govt in the Constitution of the United States the danger of encroachment by Ecclesiastical Bodies, may be illustrated by precedents already furnished in their short history.”

As president, Madison vetoed bills to incorporate the Episcopal Church in Alexandria (then part of the District of Columbia) and to provide land for a Baptist church in the Mississippi territory. He opposed exempting houses of worship from taxes and considered the appointment of congressional chaplains a violation of the establishment clause.

Given all this, there can be little doubt that Madison would have considered the posting of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms an establishment clause violation as well. As currently constituted, the Supreme Court may in due course decide otherwise and reverse Stone v. Graham.

But if it does, it should at least have the decency not to claim the support of the Father of the Constitution.

[ad_2]